CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DURING BRITISH RULE

The establishment of the East India Company in 1600 and its transformation into a ruling body from a trading one in 1765 had little immediate impact on Indian polity and governance. But the period between 1773 and 1858 under the Company rule, and then under the British Crown till 1947, witnessed a plethora of constitutional and administrative changes.

Constitutional Development between 1773 and 1858

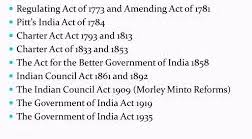

The Regulating Act of 1773

- It aimed to regulate the functioning of the East India Company.

- It recognised that the Company’s role in India extended beyond mere trade to administrative and political fields, and introduced the element of centralised administration.

- The directors of the Company were required to submit all correspondence regarding revenue affairs and civil and military administration to the government.

- In Bengal, the administration was to be carried out by governor-general and a council consisting of 4 members, representing civil and military government.

- A Supreme Court was to be established in Bengal.

- The governor-general could exercise some powers over Bombay and Madras.

Pitt’s India Act of 1784

- The Pitt’s India Act gave the British government a large measure of control over the Company’s affairs.

- The Company’s territories in India were termed ‘British possessions’.

- A Board of Control consisting of the chancellor of exchequer, a secretary of state and four members of the Privy Council were to exercise control over the Company’s civil, military and revenue affairs.

- A dual system of control was set up.

- In India, the governor-general was to have a council of three.

- Presidencies of Bombay and Madras were made subordinate to the governor-general.

Charter Act of 1793

- The Act renewed the Company’s commercial privileges for next 20 years.

- The Company, after paying the necessary expenses, etc., from the Indian revenues, was to pay 5 lakh pounds annually to the British government.

- Senior officials of the Company were debarred from leaving India without permission.

- The Company was empowered to give licences to individuals as well as the Company’s employees to trade in India.

- The revenue administration was separated from the judiciary functions.

Charter Act of 1813

- The Company’s monopoly over trade in India ended, but the Company retained the trade with China and the trade in tea.

- The Company was to retain the possession of territories and the revenue for 20 years more, without prejudice to the sovereignty of the Crown.

- Powers of the Board of Control were further enlarged.

- A sum of one lakh rupees was to be set aside for the revival, promotion and encouragement of literature, learning and science among the natives of India, every year.

- The regulations made by the Councils of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta were now required to be laid before the British Parliament.

- Christian missionaries were also permitted to come to India and preach their religion.

Charter Act of 1833

- The lease of 20 years to the Company was further extended.

- Territories of India were to be governed in the name of the Crown.

- The Company’s monopoly over trade with China and in tea also ended.

- All restrictions on European immigration and the acquisition of property in India were lifted.

- The governor-general was given the power to superintend, control and direct all civil and military affairs of the Company.

- The Governments of Madras and Bombay were drastically deprived of their legislative powers.

- A law member was added to the governor-general’s council for professional advice on law-making.

- Indian laws were to be codified and consolidated.

- No Indian citizen was to be denied employment under the Company on the basis of religion, colour, birth, descent, etc.

- The administration was urged to take steps to ultimately abolish slavery.

Charter Act of 1853

- The Company was to continue possession of territories unless the Parliament provided otherwise.

- The strength of the Court of Directors was reduced to 18.

- Services were now thrown open to a competitive examination.

- The law member became the full member of the governor-general’s executive council.

- Local representation was introduced in the Indian legislature. The legislative wing came to be known as the Indian Legislative Council.

Act for Better Government of India, 1858

- India was to be governed by and in the name of the Crown through a secretary of state and a council of 15.

- Dual system introduced by the Pitt’s India Act came to an end.

- Governor-general became the viceroy.

Developments after 1858 till Independence

Indian Councils Act, 1861

- The 1861 Act marked an advance in that the principle of representatives of non-officials in legislative bodies became accepted.

- Law-making was thus no longer seen as the exclusive business of the executive.

- The portfolio system introduced by Lord Canning laid the foundations of cabinet government in India.

- The Act by vesting legislative powers in the Governments of Bombay and Madras and by making provision for the institution of similar legislative councils in other provinces laid the foundations of legislative devolution.

- The councils could not discuss important matters and no financial matters at all without previous approval of government.

- They had no control over budget.

Indian Councils Act, 1892

- The number of non-official members was increased both in the central and provincial legislative councils.

- The Legislative Council of the Governor-General was enlarged.

- The universities, district boards, municipalities, zamindars, trade bodies and chambers of commerce were empowered to recommend members to the provincial councils. Thus was introduced the principle of representation.

- Though the term ‘election’ was firmly avoided in the Act, an element of indirect election was accepted in the selection of some of the non-official members.

- The members of the legislatures were now entitled to express their views upon financial statements which were henceforth to be made on the floor of the legislatures.

- They could also put questions within certain limits to the executive on matters of public interest after giving six days’ notice.

Indian Councils Act, 1909

- Popularly known as the Morley-Minto Reforms, the Act made the first attempt to bring in a representative and popular element in the governance of the country.

- The strength of the Imperial Legislative Council was increased.

- An Indian member was taken for the first time in the Executive Council of the Governor-General

- The members of the Provincial Executive Council were increased.

- The powers of the legislative councils, both central and provincial, were increased.

- The introduction of separate electorates for Muslims created new problems.

Government of India Act, 1919

- This Act was based on what are popularly known as the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms.

- The clarified that there would be only a gradual development of self-governing institutions in India.

- Indian Legislative Council at the Centre was replaced by a bicameral system consisting of a Council of State (Upper House) and a Legislative Assembly (Lower House).

- Each house was to have a majority of members who were directly elected.

- So, direct election was introduced, though the franchise was much restricted being based on qualifications of property, tax or education.

- The principle of communal representation was extended with separate electorates for Sikhs, Christians and Anglo-Indians, besides Muslims.

- The Act introduced dyarchy in the provinces.

- The provincial legislature was to consist of one house only (legislative council).

- The Act separated for the first time the provincial and central budgets, with provincial legislatures being authorised to make their budgets.

- A High Commissioner for India was appointed.

- The Secretary of State for India who used to get his pay from the Indian revenue was now to be paid by the British Exchequer.

- A Royal Commission would be appointed ten years after the Act to report on its working.

Government of India Act, 1935

- The Act, with 451 clauses and 15 schedules, contemplated the establishment of an All-India Federation in which Governors’ Provinces and the Chief Commissioners’ Provinces and those Indian states which might accede to be united were to be included.

- Dyarchy was provided for in the Federal Executive.

- The Federal Legislature was to have two chambers—the Council of States and the Federal Legislative. The Council of States (the Upper House) was to be a permanent body.

- There was a provision for joint sitting in cases of deadlock between the houses.

- There were to be three subject lists— the Federal Legislative List, the Provincial Legislative List and the Concurrent Legislative List.

- Residuary legislative powers were subject to the discretion of the governor-general.

- Even if a bill was passed by the federal legislature, the governor-general could veto it.

- Dyarchy in the provinces was abolished and provinces were given autonomy.

- Provincial legislatures were further expanded and bicameral legislatures were provided in the six provinces.

- The principles of ‘communal electorates’ and ‘weightage’ were further extended to depressed classes, women and labour.

- Franchise was extended, with about 10 per cent of the total population getting the right to vote.

- The Act also provided for a Federal Court.

- The India Council of the Secretary of State was abolished.

Indian Independence Act provided for the creation of two independent dominions of India and Pakistan with effect from August 15, 1947. Each dominion was to have a governor-general to be responsible for the effective operation of the Act. The constituent assembly of the each new dominion was to exercise the powers of the legislature of that dominion, and the existing Central Legislative Assembly and the Council of States were to be automatically dissolved. For the transitional period, i.e., till a new constitution was adopted by each dominion, the governments of the two dominions were to be carried on in accordance with the Government of India Act, 1935.