|

Key findings from the CAG audit:

|

High drawal rate:

Issue prices:

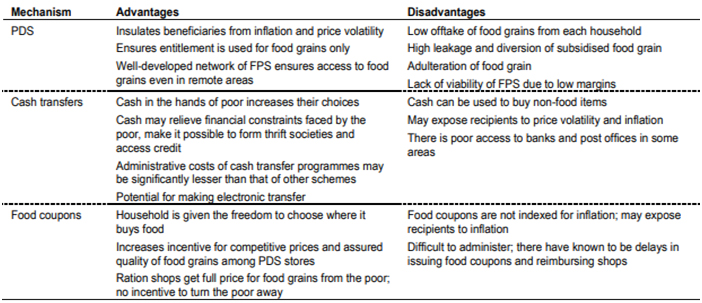

In this context, it is time the Centre had a relook at the overall food subsidy system including the pricing mechanism.

Give Up Option:

Slab System:

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved