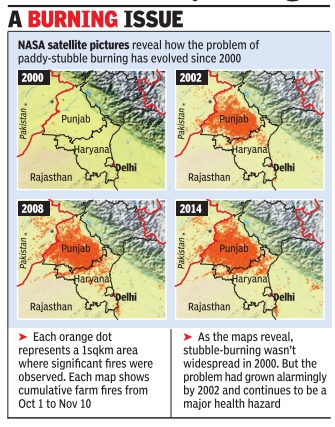

Every year around the months of October and November, farmers in states like Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh burn the stubble that is left after harvesting the paddy crop. The burning of vast fields in these states, along with the falling temperatures and decreased wind speed, contributes to air pollution in the Indo-Gangetic plains. The landlocked Delhi-NCR region in particular, gets engulfed under a cloud of poisonous smog.

For years, states have scrambled – without success – to find sustainable solutions to the problem of stubble burning. This year, the first six days of October saw five times the number of stubble-burning incidents in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh compared to the same period in 2019.

The pressing question is: How Do We Tackle Stubble Burning?

But before we discuss about the solutions let us learn about the root cause behind this menace.

Stubble burning is, quite simply, the act of removing paddy crop residue from the field to sow wheat. It’s usually required in areas that use the ‘combine harvesting’ method which leaves crop residue behind.

Now, what is combine harvesting?

Combines are machines that harvest, thresh i.e separate the grain, and also clean the separated grain, all at once. The problem, however, is that the machine doesn’t cut close enough to the ground, leaving stubble behind. This stubble is of no use for the farmer. There is pressure on the farmer to sow the next crop in time for it to achieve a full yield. The quickest and cheapest solution, therefore, is to clear the field by burning the stubble.

The main reason for paddy (rice crop) stubble burning is the short time available between rice harvesting and sowing of wheat. A delay in sowing wheat adversely affects the wheat crop. The short timeframe available between rice and wheat crops can also be attributed partly to the 2009 Punjab Preservation of Subsoil Act, where paddy transplantation date is fixed for June 20 which pushes ahead the harvesting of rice crop.

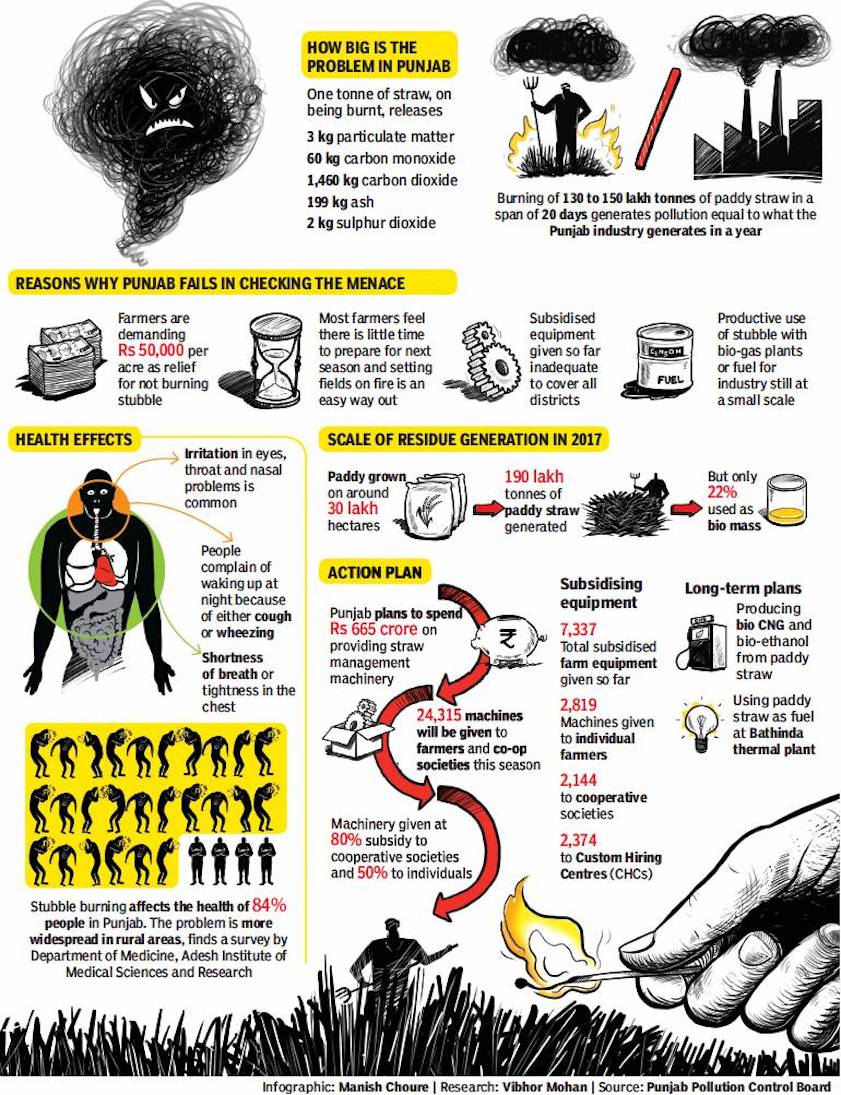

As a result farmers get less than 20-25 days between two crops. Hence the quickest and easiest solution is to burn the crop residue. It is estimated that 20 million tonnes of rice stubble are produced every year in Punjab, out of which 80% is burnt on the farm. Farmers say they don’t have the time or money to store the straw or plow the stubble back into the ground which is quite justified.

To put it simply, the traditional way of stubble-burning is easier, low cost and time-efficient, compared to alternatives that demand more time, investment and labour.

|

Do you know? Until a few decades ago, the straw generated by the machines was manageable. They could be sold to the packaging industry and also turned into mulch within the field through the natural, slow process of organic decomposition. Now, however, about 20 million tonnes of straw generated in the State, and barely two to three weeks to dispose them of and prepare the fields for the next crop. Cost-conscious farmers are left with few options other than burning the whole lot. |

Earlier when there was manual harvesting the stalk of crop remained extremely small and did not impede the sowing of fresh seed. The straw was then used as cattle feed or to make cardboard. But now most farmers rent a combine harvester which leaves up to 80% of the residue in the field. The machines leave stubble shavings that are actually 6-8 inches high, which if not cleared fresh sowing is impossible.

But farmers prefer these machines as it helps them save on the high labour costs of manual harvesting.

Food security of billions will be on stakes if technological interventions like that of Combine Harvesters are not used.

According to an August 2019 study titled ‘Fields on fire: Alternatives to crop residue burning in India,’ farmers in northwest India burn around 23 million tonnes of rice straw so that they can clear the land quickly for the sowing of wheat.

In addition to wheat and paddy, sugarcane leaves are most commonly burnt. According to official reports, more than 500 million tonnes of parali (crop residues) is produced annually in the country. Out of this cereal crops (rice, wheat, maize and millets) account for 70 per cent of the total crop residue.

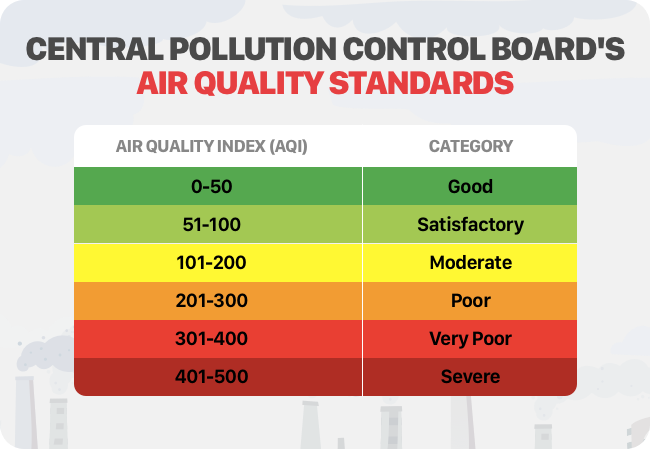

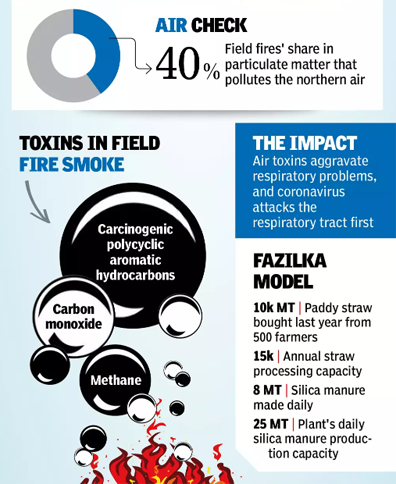

From October 2020, air quality in New Delhi and other cities in north India reached up to 20 times higher than the safe threshold levels defined by the World Health Organization.

The effects of these emissions are devastating. Air quality monitoring stations in Delhi-NCR registered above 999 on the Air Quality Index in 2019, which is way beyond emergency levels. Schools and offices were forced are forced to shut down for days.

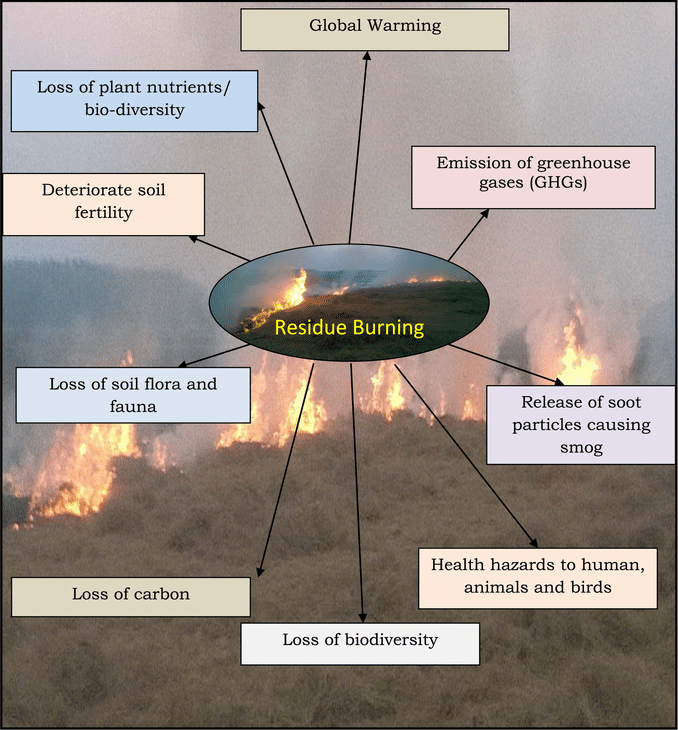

The emissions directly contribute to environmental pollution, and are also responsible for the haze in Delhi and melting of Himalayan glaciers.

Apart from contributing to air pollution, stubble-burning deteriorates the soil’s organic content, essential nutrients and microbial activity – which together will reduce the soil’s long-term productivity.

The heat from burning paddy straw penetrates 1 centimetre into the soil, elevating the temperature to 33.8 to 42.2 degree Celsius. This kills the bacterial and fungal populations critical for a fertile soil.

Burning of crop residue causes damage to other micro-organisms present in the upper layer of the soil as well as its organic quality. Due to the loss of ‘friendly’ pests, the wrath of ‘enemy’ pests has increased and as a result, crops are more prone to disease. The solubility capacity of the upper layers of soil has also been reduced.

According to reports, one ton stubble burning leads to a loss of 5.5 kilogram nitrogen, 2.3 kg phosphorus, 25 kg potassium and more than 1 kg of sulfur — all soil nutrients, besides organic carbon.

Stubble burning has been prohibited or discouraged in many countries, including China, the UK and Australia.

The cost of air pollution due to stubble burning in India is estimated to be $30 billion annually.

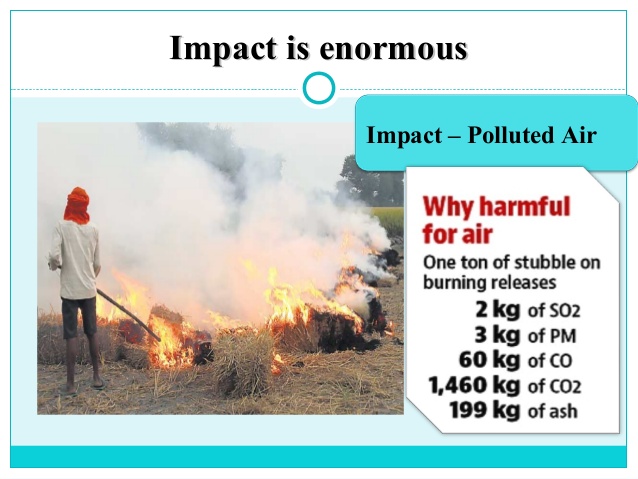

Stubble burning is a significant source of gaseous pollutants such as, carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), and methane (CH4) as well as particulate matters (PM10 and PM2.5). These air pollutants are a concern for people's health when levels in the air are high. PM 2.5 and PM10 particularly cause cancer.

The other health effects of air pollution ranges from skin and eyes irritation to severe neurological, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchitis, lung capacity loss, emphysema, cancer, etc. It also leads to an increase in mortality rates due to the prolonged exposure to high pollution.

Not really. But as mentioned earlier, it is the easiest and cheapest method available to farmers as of now. Also, most of the farmers are not aware of the prolific alternatives for managing stubble and, therefore, consider burning as the best option.

But the situation isn’t so grim after all. There are other options we can look at.

In 2014, the Union government released the National Policy for Management of Crop Residue.

Farmers can also manage crop residues effectively by employing agricultural machines like:

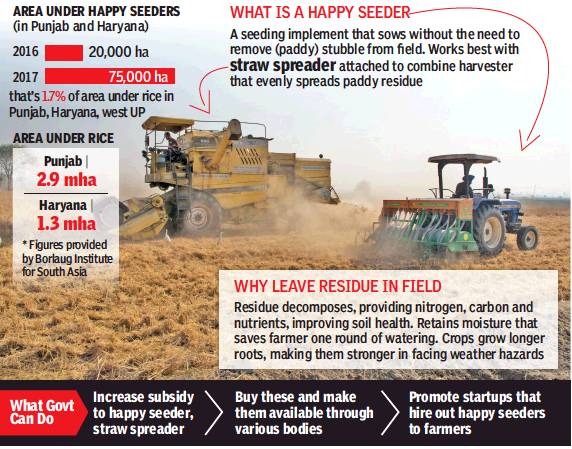

Among these, the most efficient technology to counter crop burning at the moment seems to be the Turbo Happy Seeder (THS). The THS is basically a machine mounted on a tractor that not only cuts and uproots the stubble, but can also drill wheat seeds on the soil that has just been cleared up. The straw is simultaneously thrown over the sown seeds to form a mulch cover.

The THS can also be fitted with the Super-Straw Management System (S-SMS) that spreads the straw evenly.

Waste Decomposer

Scientists at the National Centre for Organic Farming have developed a ‘Waste Decomposer’ concocted with effective microorganisms that propel in-situ composting of the crop residue.

|

The issue of affordability These agricultural equipments are expensive. So, the Union government has been providing funds so that state governments can procure these machines and make them available to farmers at no cost or at minimal cost of operation. But still the subsidies are insufficient. We shall be discussing about the gaps in Government’s policies in the later part of this article. |

Converting Crop Stubble into Animal Feed, Manure, Cardboard

In South India, stubble is not burnt as there’s economic value as animal feed.

Instead of burning of the stubble, it can be used in different ways like cattle feed, compost manure, roofing in rural areas, biomass energy, mushroom cultivation, packing materials, fuel, paper, bio-ethanol and industrial production, etc.

Converting Crop Stubble to Biodegradable Cutlery

Kriya Labs, an IIT-Delhi startup, has developed a machine that can convert the leftover rice straw into pulp, and that is further moulded to produce biodegradable cutlery.

Biochar

Another option is to convert stubble into biochar, which can be used as a fertiliser, by burning it in a kiln.

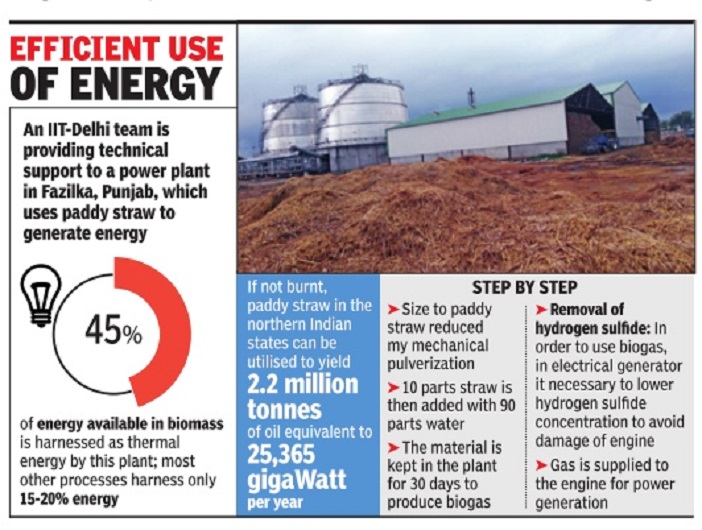

In power plants

There is also the option of using straw to replace coal in old power plants. This would not only help to extend the life of the built infrastructure, but will also reduce environmental costs.

Redesigning- Combine Harvesters

It’s important to gradually develop and improve the design of Combine Harvesters that do not leave the stubble behind. This can be done by the Combine Harvester manufacturers by slightly tweaking the design of their machines with a modified cutter that chops of the plant from the bottom, nearer to the base and does not leave behind the stubble. The government on its part should strictly regulate and allow only such Combine Harvesters to function that conform to the laid down standards of stubble size. This will eradicate the entire problem from root and cause.

Agri-Waste Collection Centers

The government may consider setting up “Agri- waste Collection Centres” alongside the “Paddy Purchase Centres”. Here, the farmers may sell their agri-waste at a reasonable price and earn some additional income and are not tempted to burn it. Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) or Farmers’ Co-operatives may be supported for purchasing of this agri-waste/ crop residue from the farmers and later selling it to industries that convert it into cattle feed or fuel.

Basically, the idea is to incentivize the farmers for not burning the stubble, by providing economic value for this crop residue or stubble, which may be converted into either cattle feed or fuel.

Incentivizing industries

The industries which are converting this agri-waste/crop residue into wealth in the form of cattle feed or fuel, may also be suitably incentivized and subsidized.

Point to Ponder

Crop Diversification - A long term solution

A shift to crops such as maize, beans and lentils need to be envisaged. This would reduce the burning because they are normally harvested by hand or can be gathered earlier. The Centre and state governments could adopt methods to incentivize farmers, rather than penalizing them. If production of other crops, like maize, is made more lucrative, then farmers will switch to growing those.

Farmers need guaranteed purchases for corn, soybeans and lentils if they are to shift from rice.

The government would also need to compensate farmers for adverse weather that can damage other crops more easily.

Another way to reduce stubble burning is to replace long-duration paddy varieties with shorter duration varieties like Pusa Basmati-1509 and PR-126. These can be harvested in the third week of September itself. This will widen the window between the end of the rice season and start of the wheat season. In this way it will give enough time for the paddy stubble to decompose, and eliminate the need for stubble-burning.

Various policy measures at the national and sub-national levels seek to resolve the problem of crop stubble burning in India. As mentioned earlier, a National Policy for Management of Crop Residues is in place, along with a Crop Diversification Programme.

According to the law, violators can be charged for non-compliance under the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act. There are also schemes to promote in situ and ex situ crop residue management through subsidized farm equipments such as the “happy seeder”, rotavator and baler. However, there are many gaps in terms of policy design, implementation and awareness.

In terms of policy design, the National Programme on crop diversification does not have clear provisions on outreach activities to inform farmers about alternate crop options.

Similarly, there is insufficient convergence with other programmes, such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, National Rural Livelihood Mission and agro-enterprise related schemes.

The inter convergence could help with the management of paddy stubble or crop diversification.

In terms of implementation, much-needed equipment is still unaffordable to many farmers despite subsidy provisions.

Constraints in the supply chain and rental markets are other issues impacting the adoption of the happy seeder and other farm machines.

Also, there is little awareness about new technologies and alternate cropping patterns.

The Chattisgarh Model of GauthanThe Chhattisgarh Government has undertaken an innovative experiment of setting up "gauthans" to curb stubble burning. A gauthan is a dedicated five-acre plot, held in common by each village, where all the unused parali is collected through parali daan (people’s donations) and is converted into organic fertilizer by rural youth. This provides them a living.The government supports the transportation of parali from the farm to the nearest gauthan. The state has already developed more than 2,000 gauthans. The Chattisgarh Model of Gauthan generates employment among rural youth as well. A committee consisting of economists, agricultural experts, farmer delegates and bureaucrats can be set up at national level to evaluate the parali burning crisis and explore the possibilities of integrating Gauthan concept with schemes like the MGNREGA by expanding the MGNREGA scheme to harvesting and composting. |

Punjab and Haryana started penalizing farmers indulging in stubble burning. The Supreme Court has also sought response from the Centre and others on a plea seeking directions to ban stubble completely.

However despite imposition of heavy fines, stubble burning cases continued unabated. According to farmers, they are forced to resort to this method because of the lack of options provided by the government.

Farmers have also noted that hiring stubble-removing machines is not financially viable, as most marginal farmers cannot afford them. This is because big farmers who set up the stubble-removing machines charge high rents, even after purchasing the implements at 80 per cent subsidy.

Thus, a complete ban though appears to be the most suited option; it is not feasible unless and until issues like non-availability of machines to small farmers are addressed. Tardy implementation of Government Schemes is adding to the problem.

Some farmer unions are even confronting the officials making surprise checks in the fields and imposing fines on farmers found burning stubble. What has complicated the matter is the government’s soft approach on cracking the whip against farmers who form an influential vote bank.

The Supreme Court has been asking if the MSP can be withheld over farm fires. It amounts to withholding a portion of the minimum support price and releasing it later only after a verification that the stubble was not burnt.

However, this appears to be a bit hasty. The government provides MSP on 23 crops but not all are purchased at support price, mostly those that are vital for food security. Also, not all farmers are able to sell at the MSP and with their level of awareness, the chances of their getting unfairly penalized are real.

It will also give the implementing agencies a handle to harass the farmers. The government should instead examine the possibility of roping in agencies involved in agricultural marketing in the task of managing crop stubble. With its elaborate state machinery, the problem should not be left alone for the farmers to solve.

A holistic approach is required to address crop residue burning. This includes a multi-disciplinary and multi-agency setting involving

In the short term, misconceptions among farmers regarding paddy straw management needs to be resolved. These misconceptions include improvement in soil fertility due to stubble burning and reduction in yield due to use of in situ machines.

Even though national schemes provide for establishing farm machinery banks to provide hiring services to farmers, there are serious issues of timely availability of machines to farmers.

In the medium term (that is the next seven years), there is a need to encourage crop diversification and rotation.

While technological interventions for the management of crop residue may be useful in the short term, crop diversification as a policy intervention needs to be emphasized by the government.

This is also in context of multiple environmental externalities of present cropping patterns, such as depleting groundwater, poor soil quality and air pollution.

Crop diversification can improve resilience from the effects of greater climate variability and extreme events. It can be implemented in various ways such as crop rotation, poly-cultures, increased structural diversity, or agroforestry.

There also needs to be a central coordinating mechanism for paddy stubble management and crop diversification with adequate resources, and a clear assignment of responsibilities between national and sub-national agencies. The target should be putting a stop on crop residue burning at any cost, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A detailed study involving all stakeholders is required to understand the reason behind slow progress towards crop diversification in spite of regulatory policy nudges and fiscal policy incentives by both central and state governments.

A push towards crop diversification package should be a mix of policy measures such as encouragement of agro-business enterprises – possibly under Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliant India) – farmer awareness campaigns, economic incentives such as minimum support prices for alternative crops, along with infrastructure support such as agricultural inputs for identified alternative crops, cold storage facilities and market promotion mechanisms.

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved