TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE OF INDIA

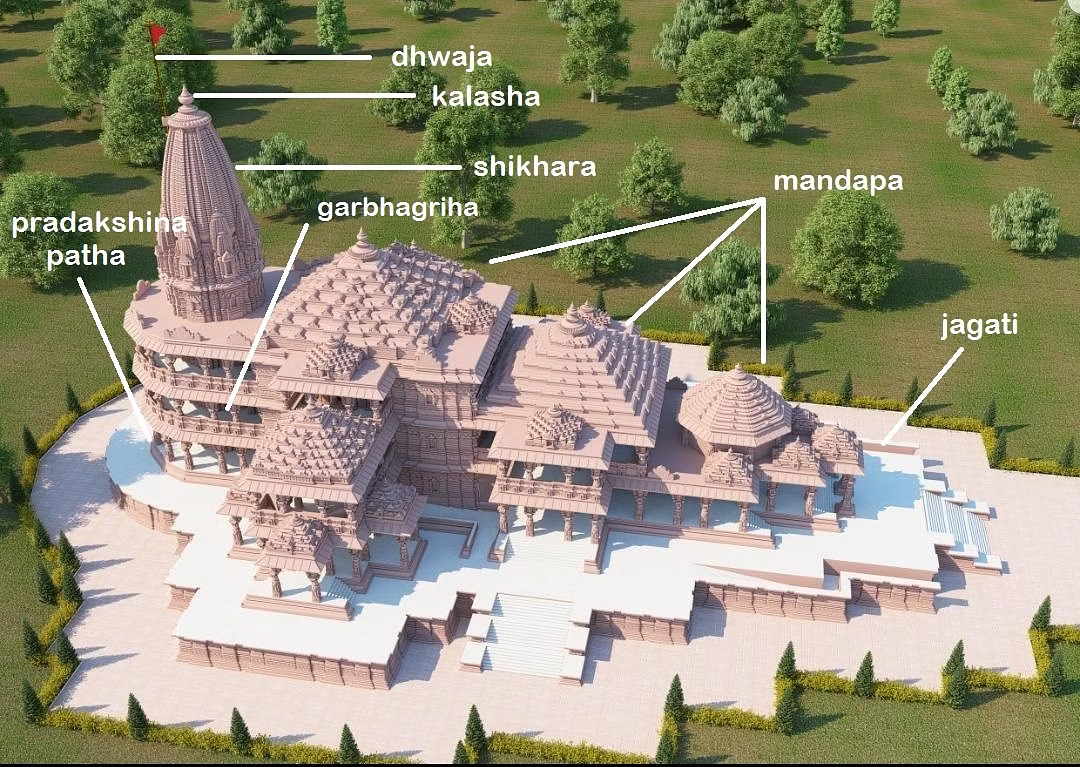

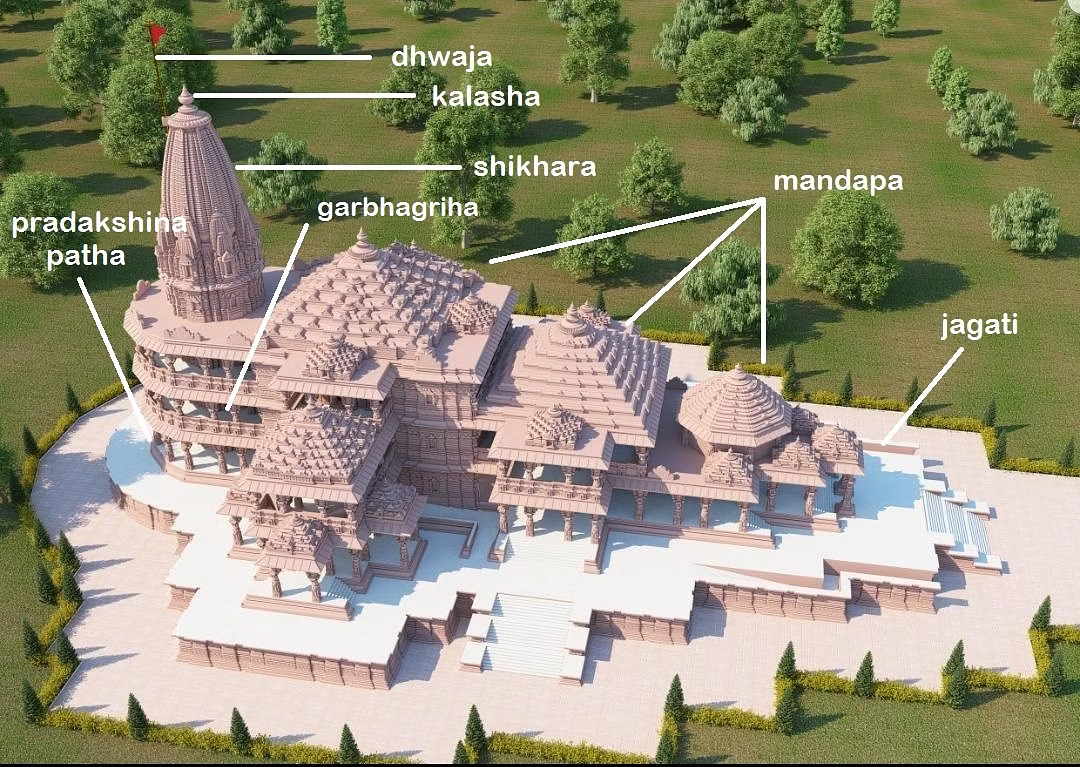

The Nagara style of temple architecture, in which Ayodhya's Ram temple is being built, is a significant tradition with its roots in northern India.

The Nagara or North Indian Temple Style

The Nagara style of temple architecture, prevalent in northern India, is a testament to the rich cultural and artistic heritage of the region. This distinctive architectural tradition has evolved over centuries, showcasing a myriad of features that set it apart from its southern counterpart, the Dravida style.

Foundation and Layout:

- Stone Platforms and Steps: Commonly, Nagara temples are built on stone platforms with ascending steps, creating an elevated structure.

- Absence of Elaborate Boundaries: Unlike South Indian temples, Nagara structures typically lack elaborate boundary walls or gateways, emphasizing simplicity.

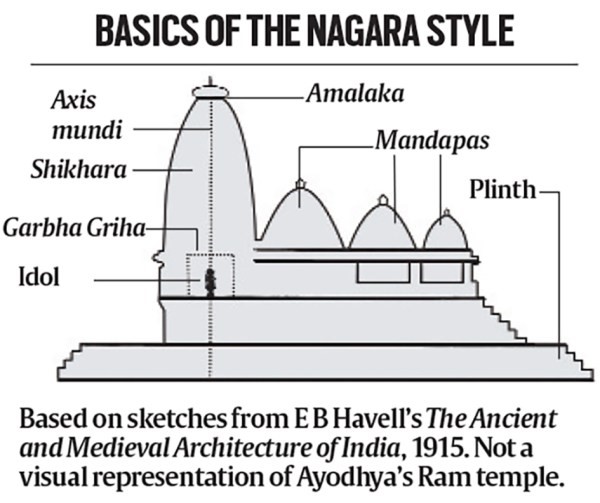

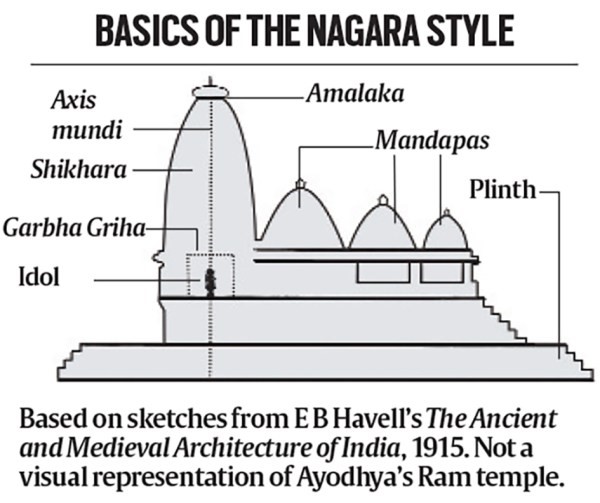

Evolution of Shikharas:

- Single to Multiple Towers: Early temples featured a single tower, or shikhara, while later structures embraced multiple shikharas.

- Garbhagriha Placement: The garbhagriha, housing the sacred idol, is consistently positioned directly under the tallest tower, symbolizing its significance.

Subdivisions Based on Shikhara Shapes:

- Latina or Rekha-Prasada Type: Characterized by a square base, the latina or rekha-prasada shikhara has walls that gracefully curve or slope inward towards a pointed top.

Phamsana:

- Broader and Shorter Design: Phamsana buildings are broader and shorter compared to the latina ones.

- Slab Roofs: Roofs consist of several slabs gently rising to a single point over the central part of the building, offering a distinct architectural profile.

Complex Latina Structures:

- Evolution of Latina Buildings: Over time, latina buildings became more intricate. Instead of a single tall tower, they started supporting numerous smaller towers, forming a cluster resembling rising mountain peaks.

- Central Tallest Tower: The central and tallest tower within this cluster consistently stands above the garbhagriha, maintaining a visual and symbolic prominence.

Valabhi Type:

- Rectangular Buildings with Vaulted Chambers: Valabhi structures are characterized by rectangular buildings with roofs rising into a vaulted chamber.

- Wagon-Vaulted Influence: The rounded edge of the vaulted chamber is reminiscent of ancient wagons drawn by bullocks, showcasing influence from pre-existing architectural forms.

Influences from Ancient Building Forms:

- Buddhist Rock-Cut Chaitya Caves: The Nagara temple style is influenced by ancient building forms predating the 5th century CE. For example, the valabhi type draws parallels with the ground-plan of Buddhist rock-cut chaitya caves, featuring long halls ending in a curved back with a wagon-vaulted roof.

Nagara style of temple architecture in northern India is a captivating journey through time and cultural influences. Its diverse shikhara shapes, evolving designs, and incorporation of ancient forms contribute to the unique and enduring charm of Nagara temples, offering a glimpse into the architectural brilliance of the region.

Temples of Central India

Central India, encompassing regions like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, boasts a rich legacy of ancient temples. These temples, primarily constructed from sandstone, bear witness to the diverse architectural styles and cultural influences that have shaped the region over centuries.

Gupta Period Temples:

- Some of the oldest surviving structural temples from the Gupta Period are found in Madhya Pradesh.

- These modest-looking shrines feature four pillars supporting a small mandapa, resembling a simple square porch-like extension, and a small room serving as the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum).

Udaigiri and Sanchi:

- Two surviving temples, notably at Udaigiri and Sanchi, exemplify architectural innovations during this period.

- Udaigiri, on the outskirts of Vidisha, and Sanchi, near the stupa, showcase developments such as a flat roof, indicating shared architectural influences between Hindu and Buddhist structures.

Deogarh Temple:

- Built in the early sixth century CE, the Deogarh temple in Uttar Pradesh exemplifies the late Gupta Period.

- Following the panchayatana style, it features a rectangular plinth with four smaller subsidiary shrines at the corners, with a tall and curvilinear shikhara, indicating an early example of classic Nagara-style temple architecture.

Vishnu Temple at Deogarh:

- The west-facing temple depicts Vishnu in various forms, including Sheshashayana, Nara-Narayan, and Gajendramoksha.

- The grand doorway features standing sculptures of female figures representing the Ganga and the Yamuna.

- The temple, with reliefs of Vishnu on its walls, remains an early example of Nagara-style architecture.

Khajuraho Temples:

- Temples in Khajuraho, built by the Chandela Kings in the tenth century, showcase a dramatic evolution in Nagara temple architecture.

- The Lakshmana Temple, dedicated to Vishnu, stands on a high platform with four smaller temples in the corners, featuring towers rising in a curved pyramidal fashion.

- The Kandariya Mahadeo temple epitomizes Central Indian temple architecture, known for its massive structure and intricate sculptures.

Erotic Sculptures and Mithun Sculptures:

- Khajuraho's temples, including the Kandariya Mahadeo temple, are renowned for extensive erotic sculptures.

- Mithun sculptures, symbolizing an embracing couple and considered auspicious, are featured in many Hindu temples, often placed at entrances or on exterior walls.

Chausanth Yogini Temple:

- Predating the tenth century, the Chausanth Yogini temple is constructed from roughly-hewn granite blocks.

- Dedicated to devis or goddesses associated with the rise of Tantric worship, these temples were built across Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu between the seventh and tenth centuries.

The temples of Central India form a captivating narrative of architectural evolution and cultural diversity. From the modest Gupta Period structures to the dramatic temples of Khajuraho, each temple tells a story of artistic expression, spiritual significance, and the enduring legacy of the region's rich cultural heritage.

Temples of West India

The north-western regions of India, including Gujarat and Rajasthan, boast a plethora of temples that showcase a rich tapestry of architectural styles and artistic expressions. The use of varied stones, including sandstone, basalt, and marble, contributes to the unique character of these temples.

Diversity in Stone Usage:

- Temples in this region use a variety of stones, with sandstone being the most common. Grey to black basalt is observed in some tenth to twelfth-century temple sculptures.

- White marble, known for its manipulatable quality, is prominently featured in Jain temples in Mount Abu (tenth to twelfth century) and the fifteenth-century temple at Ranakpur.

Samlaji in Gujarat:

- Samlaji in Gujarat is an important art-historical site where artistic traditions of the region merged with a post-Gupta style, giving rise to a distinct sculpture style.

- Numerous sculptures made of grey schist dating between the sixth and eighth centuries CE have been discovered in this region, reflecting a unique artistic blend.

Sun Temple at Modhera:

- The Sun Temple at Modhera, built by Raja Bhimdev I of the Solanki Dynasty in 1026, stands as a testament to the architectural brilliance of the early eleventh century.

- A rectangular stepped tank, known as Surya Kund, stands in front of the temple, showcasing a grand temple tank adorned with a hundred and eight miniature shrines.

Architectural Features:

- Proximity of sacred architecture to water bodies, such as tanks, rivers, or ponds, has been a tradition observed since ancient times and is evident in the design of the Surya Kund.

- An ornamental arch-torana leads to the sabha mandapa (assembly hall), an open structure characteristic of western and central Indian temples during the eleventh century.

Woodcarving Tradition of Gujarat:

- The influence of the woodcarving tradition of Gujarat is discernible in the lavish carving and sculpture work adorning the temples in the region.

- Notably, the central small shrine's walls are left plain to allow direct sunlight during equinoxes, a testament to the thoughtful integration of natural elements into temple architecture.

The temples of West India, with their diverse stones, architectural styles, and artistic influences, stand as captivating witnesses to the cultural and historical legacy of the region. From the ancient sculptures of Samlaji to the grandeur of the Sun Temple at Modhera, each temple contributes to the rich mosaic of India's architectural heritage.

Temples of East India

Eastern India, encompassing the North-East, Bengal, and Odisha, showcases a diverse array of temples, each region contributing to the cultural tapestry with distinct architectural styles and historical influences.

North-East:

- In the North-East, the history of architecture is challenging to trace due to renovations and the prevalence of later brick or concrete temples.

- Terracotta was a primary construction medium, and plaques depicted Buddhist and Hindu deities until the seventh century.

- Assam, influenced by Gupta art, developed its unique style by the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, known as the Ahom style, a blend of the Pala style of Bengal and the migration of the Tais from Upper Burma.

Assam:

- Assam's Kamakhya temple, built in the seventeenth century, stands as a testament to the unique Ahom style, dedicated to Goddess Kamakhya.

- The region witnessed a transition from the post-Gupta style to a distinctive regional style influenced by migration and artistic fusion.

Bengal:

- Bengal's Pala style (ninth to eleventh centuries) and Sena style (eleventh to thirteenth centuries) reflect the influence of ruling dynasties.

- The Siddheshvara Mahadeva temple in Barakar, Burdwan District, exemplifies the early Pala style, featuring a tall curving shikhara crowned by a large amalaka.

- Terracotta brick temples, prevalent in the seventeenth century around Vishnupur, Bankura, Burdwan, and Birbhum, showcase a fusion of local techniques, Pala influences, and Islamic architecture elements.

Bengal's Vernacular Traditions:

- Bengal's local vernacular traditions, including the curving side of bamboo hut roofs, influenced temple styles and even shaped the iconic Bangla roof, later adopted in Mughal architecture.

- Terracotta brick temples in the seventeenth century blended local building techniques, Pala forms, and Islamic architectural elements.

Eastern India's temples, with their distinct regional styles, reflect the rich heritage and evolution of artistic expression. From the terracotta temples of Bengal to the unique Ahom style in Assam, each temple narrates a story of cultural amalgamation and artistic innovation that has shaped the identity of this vibrant region.

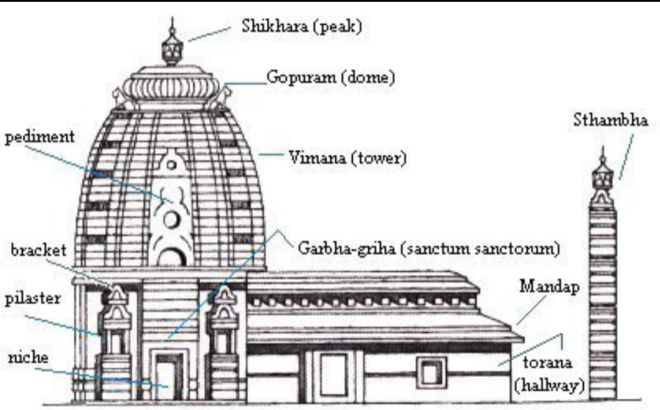

Odisha Temples

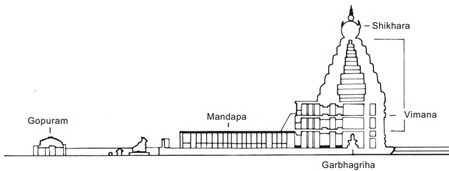

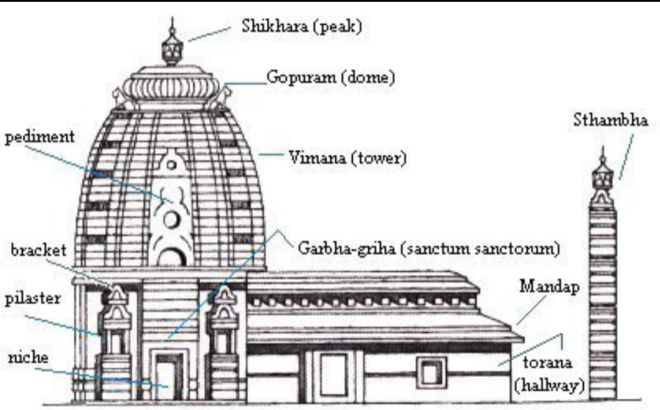

Odisha, particularly in the ancient Kalinga region encompassing Puri, Bhubaneswar, and Konark, boasts a unique style of temple architecture classified into three orders: rekhapida, pidhadeul, and khakra.

Rekhapida, Pidhadeul, and Khakra Orders:

- Rekhapida: The main temples exhibit a distinct shikhara called deul in Odisha. Unlike other nagara styles, the deul is vertical until the top, where it sharply curves inwards.

- Pidhadeul: The main temples are accompanied by mandapas called jagamohana in Odisha. The ground plan is usually square, evolving into a circular crowning mastaka, giving the spire a nearly cylindrical appearance.

- Khakra: Compartments and niches within the temples are generally square, and exteriors are richly carved. The overall appearance is cylindrical in length. Odisha temples often feature boundary walls.

The Sun Temple:

- The Sun temple at Konark, built around 1240, stands as a majestic example of Odisha temple architecture.

- The shikhara of the Sun temple, once colossal and reaching 70m, fell in the nineteenth century due to its weight.

- The surviving jagamohana, considered the largest enclosed space in Hindu architecture, is part of the vast complex near the Bay of Bengal.

Architectural Features:

- Ornamental Carving: The Sun temple's walls are adorned with extensive and detailed ornamental carvings. Notable are twelve pairs of enormous wheels, symbolizing the chariot wheels of the Sun god, drawn by eight horses.

- Colossal Processional Chariot: The overall design of the temple resembles a colossal processional chariot, paying homage to the Sun god's mythical chariot.

- Surya Sculptures: Massive sculptures of Surya, the Sun god, are carved out of different stones, placed on different temple walls facing various directions. The southern wall features a significant Surya sculpture made of green stone.

- Symbolic Entrance: The temple's southern wall had sculptures of the Sun god, with the entrance doorway positioned in such a way that the actual rays of the sun would enter the garbhagriha.

Odisha temples, with their unique blend of vertical deuls, mandapas, and intricate carvings, showcase a distinctive sub-style within the nagara order. The Sun temple at Konark, a testament to Odisha's architectural brilliance, stands as a captivating example of ancient craftsmanship and mythological symbolism.

Hills: Kumaon, Garhwal, Himachal, and Kashmir

The hills of Kumaon, Garhwal, Himachal, and Kashmir have given rise to a unique form of architecture, shaped by a blend of influences from prominent Gandhara sites, Gupta traditions, and local practices.

Cultural Mélange in the Hills:

- Gandhara Influence: The proximity of Kashmir to significant Gandhara sites by the fifth century CE led to a strong Gandhara influence. This influence intertwined with Gupta and post-Gupta traditions from places like Sarnath, Mathura, Gujarat, and Bengal.

- Intermingling Traditions: Frequent travel of Brahmin pundits and Buddhist monks between Kashmir, Garhwal, Kumaon, and plains' religious centers resulted in the intermingling of Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

Architectural Fusion:

- Wooden Buildings with Pitched Roofs: The hills had their tradition of wooden buildings with pitched roofs. In some hill temples, the main garbhagriha and shikhara follow a rekha-prasada or latina style, while the mandapa retains an older wooden architecture. Occasionally, the temple itself adopts a pagoda shape.

Temples of Significance:

- Pandrethan Temple (Kashmir): Built during the eighth and ninth centuries, Pandrethan Temple is a significant example of Karkota period architecture in Kashmir. It stands on a plinth in the middle of a tank, showcasing the tradition of having a water tank attached to the shrine. Moderately ornamented, the temple reflects the Kashmiri tradition of wooden buildings, featuring a peaked roof slanting outward.

Sculptural Amalgamation at Chamba:

- Chamba (Himachal Pradesh): Sculptures at Chamba display a fusion of local traditions with a post-Gupta style. Images like Mahishasuramardini and Narasimha at the Laksna-Devi Mandir reflect the influence of the post-Gupta tradition and the metal sculpture tradition of Kashmir. The yellow color of the images suggests the use of a zinc and copper alloy, popular in Kashmir.

Temples in Kumaon:

- Jageshwar and Champavat: Temples in Jageshwar near Almora and Champavat near Pithoragarh are exemplary of nagara architecture in Kumaon. These temples showcase the characteristic features of the style prevalent in North India.

The hills' architecture stands as a testament to the rich cultural exchanges and adaptability, where diverse influences converge to create unique and harmonious structures, reflecting the spiritual ethos of the region.

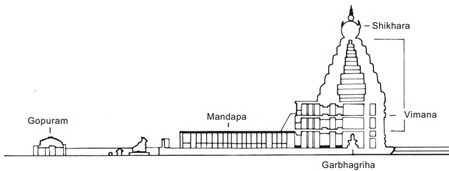

The Dravida or South Indian Temple Style

The Dravida temple style, prevalent in South India, exhibits distinctive features in its architecture and layout, reflecting the rich cultural and religious traditions of the region.

Compound Structure:

- Gopuram: The Dravida temple is enclosed within a compound wall with an entrance gateway known as the gopuram, typically situated at the front wall's center.

Vimana and Shikhara:

- Vimana: The main temple tower, called vimana in Tamil Nadu, resembles a stepped pyramid, rising geometrically rather than the curving shikhara of North Indian temples.

- Shikhara in Dravida Temples: In the South Indian context, the term 'shikhara' specifically refers to the crowning element at the top of the temple, often shaped like a small stupika or an octagonal cupola, equivalent to the amlak and kalasha of North Indian temples.

Iconography and Sculptures:

- Entrance Sculptures: Unlike North Indian temples, where the entrance might feature mithunas, Ganga, and Yamuna, Dravida temples often display sculptures of fierce dvarapalas (door-keepers) guarding the temple.

- Temple Tanks: It is common to find a large water reservoir or temple tank enclosed within the temple complex.

Urban Architecture and Temple Towns:

- Focus on Urban Architecture: Temples became not only religious centers but also rich administrative hubs, controlling vast areas of land in temple towns like Kanchipuram, Thanjavur, Madurai, and Kumbakonam.

Subdivisions of Dravida Temples:

- Shapes: Dravida temples can be of various shapes, including square (kuta or caturasra), rectangular (shala or ayatasra), elliptical (gaja-prishta or vrittayata), circular (vritta), and octagonal (ashtasra).

- Adaptability: The temple's plan and vimana shape were often influenced by the iconographic nature of the consecrated deity, leading to unique styles based on specific requirements.

Pallavas and Early Temples:

- Pallavas: The Pallavas, an ancient South Indian dynasty, contributed significantly to the Dravida temple style. They were active from the second century CE onwards in the Andhra region before settling in Tamil Nadu.

- Mahabalipuram: Early Pallava buildings, like those in Mahabalipuram, showcase rock-cut and later structural temples. Mamalla, also known as Narasimhavarman I, expanded the empire and initiated several building works at Mahabalipuram.

Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram:

- Orientation: The Shore Temple, likely built in the reign of Narasimhavarman II, is oriented to the east facing the ocean. It houses three shrines, two to Shiva and one to Vishnu, with evidence of water tanks and early gopurams.

Brihadiswara Temple in Thanjavur:

- Rajarajeswara Temple: Completed around 1009 by Rajaraja Chola, the Brihadiswara temple in Thanjavur is the largest and tallest of all Indian temples.

- Scale: Standing at a massive seventy meters, the temple features a pyramidal multi-storeyed vimana topped by an octagonal dome-shaped stupika.

- Gopuras and Sculptural Program: Notably, it includes two large gopuras with elaborate sculptural programs, showcasing the grandeur of Chola temple architecture.

- Main Deity: Dedicated to Shiva, the temple's sanctum houses a huge lingam set in a two-storeyed structure.

The Dravida temple style stands as a testament to the vibrant religious and artistic traditions of South India, characterized by its unique architectural elements, sculptural richness, and the integration of temples into the broader urban fabric.

Architecture in the Deccan

The Deccan region of India exhibits a diverse range of temple architecture styles influenced by both North and South Indian traditions.

Vesara Style:

- Hybridization: In regions like Karnataka, a hybridized style known as vesara emerged after the mid-seventh century, incorporating elements from both nagara and dravida traditions.

Ellora and Rashtrakutas:

- Ellora Complex: Ellora, known for its ambitious projects, saw grander developments by the late seventh or early eighth century.

- Rashtrakutas' Kailashnath Temple: The Rashtrakutas' Kailashnath temple at Ellora, dedicated to Shiva, is a complete dravida structure carved out of living rock. The site includes a Nandi shrine, gopuram-like gateway, cloisters, and a towering vimana.

Chalukyan Contributions:

- Western Chalukyas: The early western Chalukyas, starting with Pulakesin I in 543, contributed to rock-cut caves initially and later to structural temples.

- Ravana Phadi Cave: The Ravana Phadi cave at Aihole, with its distinctive sculptural style, includes important sculptures like Nataraja and saptamatrikas.

Chalukyan Hybrid Styles:

- Pattadakal Temples: The Chalukyan temples at Pattadakal, particularly the one built by Vikramaditya II, showcase a blend of dravida and Pallava styles, reflecting the assimilation of various influences.

- Durga Temple at Aihole: The Durga temple at Aihole stands out with an early apsidal shrine and a shikhara stylistically reminiscent of nagara architecture.

Lad Khan Temple:

- Experimental Styles: The Lad Khan temple at Aihole appears inspired by wooden-roofed hill temples but is constructed entirely in stone, showcasing the innovative spirit of Chalukyan architects.

Hoysala Temples:

- Complexity and Soapstone: Hoysala temples, including those at Belur, Halebid, and Somnathpuram, feature complex stellate plans and intricate carvings. Carved from soapstone, the temples exhibit intricate jewelry on the deity sculptures.

- Hoysaleshvara Temple at Halebid: The Hoysaleshvara temple at Halebid, dedicated to Shiva as Nataraja, is a prime example of Hoysala architecture, characterized by a unique blend of dravida and nagara styles.

Vijayanagara Empire:

- Cultural Synthesis: Vijayanagara, founded in 1336, witnessed a synthesis of dravida temple architecture with Islamic styles from neighboring sultanates.

- International Travelers: The city attracted international travelers, and their accounts, along with Sanskrit and Telugu works, provide insights into the vibrant literary and architectural traditions of Vijayanagara.

Cultural Fusion:

- Eclectic Ruins: The ruins from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in Vijayanagara showcase an eclectic blend of styles, marking an age of wealth, exploration, and cultural fusion.

The Deccan region's architectural diversity reflects the creative expressions of architects who adapted, innovated, and competed with their counterparts across India. These buildings stand as dynamic expressions of India's rich art-historical heritage.

Buddhist and Jain Architectural Developments

During the period from the fifth to the fourteenth centuries, Buddhist and Jain architectural developments were vibrant and coexisted alongside Hindu architecture.

Buddhist Developments

- Bodhgaya:

- Significance: Bodhgaya is a major Buddhist pilgrimage site where Gautama Buddha attained enlightenment. The Mahabodhi Temple, constructed around the bodhi tree, is a testament to the brickwork of that time.

- Historical Layers: King Ashoka is believed to have constructed the first shrine, the vedika around it is post-Mauryan, and sculptures in the temple's niches date back to the eighth century Pala Period. The temple's current design is a Colonial Period reconstruction.

- Nalanda:

- Mahavihara: Nalanda was a renowned Buddhist monastic university and mahavihara. The foundation was laid in the fifth century CE by Kumargupta I, and the university flourished with teachings of Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana doctrines.

- Influence: Monks and pilgrims from various Asian countries frequented Nalanda, contributing to the spread of Buddhist art and ideas across the region.

- Sculptural Art: Nalanda's sculptural art, in stucco, stone, and bronze, evolved through a synthesis of Gupta art, local Bihar traditions, and central Indian influences. The sculptures, dating between the seventh and twelfth centuries, depict Mahayana and Vajrayana deities.

- Sirpur:

- Location: Sirpur in Chhattisgarh, an early-Odisha-style site (550–800), features both Hindu and Buddhist shrines with iconographic and stylistic similarities to Nalanda.

- Jain Influence: Sirpur also has Jain temples, highlighting the coexistence of Buddhist and Jain influences in the region.

- Nagapattinam:

- Trading Hub: Nagapattinam served as a major Buddhist center, benefiting from trade with Sri Lanka, where a significant Buddhist population existed.

- Chola Period: Bronze and stone sculptures in the Chola style, dating back to the tenth century, have been unearthed at Nagapattinam.

Jain Developments

- Mount Abu:

- Construction: The Jain temples at Mount Abu were constructed by Vimal Shah. They feature a simplistic exterior and rich sculptural decoration with intricate lace-like patterns.

- Shatrunjay Hills (Palitana):

- Significance: Located near Palitana in Kathiawar, Gujarat, the Shatrunjay hills house an imposing cluster of Jain temples, making it a significant pilgrimage site.

- Architectural Diversity: Scores of temples, each with unique architecture, contribute to the grandeur of the site.

- Other Regions:

- Rich Heritage: Jainism has a rich temple-building tradition across India, particularly in Bihar, Deccan (Ellora and Aihole), Central India (Deogarh, Khajuraho, Chanderi, Gwalior), and Karnataka.

- Gomateshwara Statue: Sravana Belagola in Karnataka is famous for the world's tallest monolithic free-standing structure, the eighteen-meter-high statue of Gomateshwara.

- Gujarat and Rajasthan:

- Strongholds: Gujarat and Rajasthan have been strongholds of Jainism since early times, with famous hoards of Jain bronzes discovered at Akota and other sites.

The Buddhist and Jain architectural developments during this period contributed significantly to the cultural and artistic landscape of India. Monastic centers like Nalanda served as hubs for art production, disseminating ideas across Asia. Jainism, with its extensive temple-building tradition, left a lasting impact on regions across India, showcasing architectural diversity and craftsmanship. The coexistence of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain monuments in various sites exemplifies the syncretic nature of Indian culture during this era.