For a banking sector dependent economy like India, good health of the banks is very important to ensure accessible financial services and flow of credit to support the growing economy. Unfortunately, for many years, Indian banks have been dealing with a crisis that has created problems for them and the entire economy.

The quest to find a solution to this problem has further gained momentum after the economic fallout from the COVID pandemic. One of the many measures that have been proposed is the idea of setting up a National bad bank.

This article explains the concept of a bad bank, some history of the banking sector crisis, the ongoing debate on bad banks, the bold proposal that has been made to set up a bad bank in India, and the possibility of it being considered by the Government.

A ‘bad bank’ is a bank that buys the bad loans of other lenders and financial institutions to help clear their balance sheets. The bad bank then resolves these bad assets over a period of time. When the banks are freed of the NPA burden, they can take a more positive look at the new loans. Ideally, such a bank should be owned by the banks which have the most of NPAs.

|

When does a loan turn 'bad'? The banking sector is the backbone of the economy as it provides credit to fund different economic activities. Sometimes these loans turn into bad loans. Bad loans, also called as non-performing assets (NPA’s) are those loans made by a bank on which the borrower has not made interest or principal repayments on time. These loans are classified as non-performing and are at the verge of or already in the state of default. These bad loans negatively impact a bank’s balance sheet. Thus, several leading economists feel “bad bank” could be a good idea to free the banks from the mounting burden of the NPAs. |

The bad bank is similar to an asset reconstruction company (ARC), where they absorb these loans from the banks and then manage them to recover as much amount as possible. They help remove the burden of these loans from the banks’ books, allowing the banks to increase their profitability and solely focus on core lending while transferring risk to the bad bank. Having a clean balance sheet also enhances a bank’s ability to raise more capital and instill confidence among its investors.

India’s economy has been dependent to a large extent on the banking sector. Corporates have heavily relied on bank credit to fund their growth and expansion. India experienced an economic boom starting in 2003-2004, with the GDP growing at an average rate of close to 9%.

The big companies, sensing an opportunity, borrowed heavily from the banks to fund their growth and expansion. Moreover, the banks were more than willing to lend to the corporate sector at very low interest rates and without much due diligence.

But after the 2008 financial crisis, India’s economy experienced a slowdown, and many companies found it difficult to pay back the huge loans they had taken. For many years, this did not come to light as banks kept on restructuring, giving even more loans to these companies hoping that there would be a turn-around in these companies, as the economic conditions improve. Banks, mostly the public sector banks kept on ever-greening these loans and did not recognize them as Non-performing assets in their balance sheets, did not make provisions as it would hurt their profitability.

The problem got worse day by day, and the number of bad loans kept increasing. Consequently, as a lot of bank’s resources got locked up in these loans, bank lending and credit growth started to fall. The extent of this problem came to light during the 2014 asset quality review of the banking sector by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The central bank took immediate actions– it scrutinized the banks and introduced new regulations regarding the recognition and reporting of non-performing assets in the banks’ balance sheet.

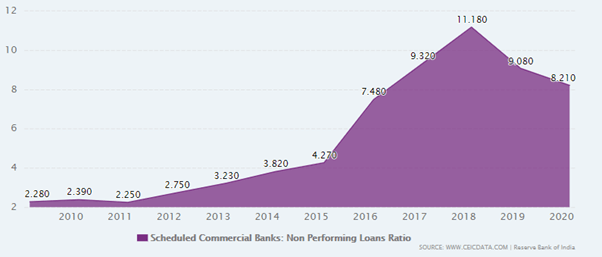

Gross NPA ratio is a measure of the NPA in the banking sector. It is calculated as a ratio of the non-performing loans to the total loans and advanced by scheduled commercial banks. As shown in the figure below, the gross NPA ratio drastically increased from 2.2% in 2009 to about 11.1% in 2018; the total amount of NPA surpassing Rs.10 trillion. India had among the highest NPA ratios in the world.

Most of the NPA’s were generated by the public sector banks, accounting for over 70% of the NPA of the entire banking sector. The trend of high profile companies borrowing huge sums from PSB’s and then willfully defaulting on these loans became evident. Moreover, many banking frauds came into light involving the public sector banks. The root causes of the NPA crisis were – high inefficiency and poor governance in the public sector banks, lack of due diligence and regulation and even outright fraud.

RBI and the Government took steps to address this problem, which was adversely impacting the flow of credit within the economy. Strict regulations by the RBI, reforms like The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC -2016), and bank recapitalization efforts by the Government helped reduce the gross NPA ratio in the banking sector to 8.5% in March 2020.

But due to the impact of COVID crisis on economic activity, many corporates find themselves in a difficult financial situation and once again the NPA ratio is poised to increase.

Also, because of the government support, moratorium on loans and the relaxation to banks on NPA reporting, the true extent of the increase in NPA’s unknown.

But according to latest estimates by the RBI in its financial stability report, the gross NPA’s may increase to 12.5% in March 2021 or in the worst scenario it may also escalate to 14.5%.

In May 2020, the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), a body representing major Indian banks submitted a proposal to the RBI and Government to set up a national Bad Bank. According to the proposal, the bad bank would initially start with a book of approximately Rs.75000 Crores worth of bad loans.

A bad bank would allow banks to devote more time and effort to lending and flow of credit instead of being burdened with the recovery of past loans. As bad loans ratio is expected to increase in the next few months due to the damage caused by the pandemic, it is argued that the time is ripe for the Government to set up a bad bank as it would help banks to deal with the spike in NPA’s and to assess the true extent of bad loans post the pandemic.

|

Raghuram Rajan on Bad Banks Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan had opposed the idea of setting up a bad bank in which banks hold a majority stake. “I just saw this (bad bank idea) as shifting loans from one government pocket (the public sector banks) to another (the bad bank) and did not see how it would improve matters. Indeed, if the bad bank were in the public sector, the reluctance to act would merely be shifted to the bad bank,” Rajan wrote in his book I Do What I Do. |

|

International Experience on Bad Banks Countries like the UK, the US, Spain, Malaysia, France, Finland, Belgium, Germany, Austria and Sweden have successfully experimented with bad asset resolution through a bad bank. The earliest case was of the Mellon Bank in 1988—to hold bad assets of $1.4 billion. The UK Asset Resolution (UKAR), a bad bank, repaid 48.7 billion pound taxpayers’ loan that it had taken, and is close to selling the last of its asset portfolio before winding down. International experience should come handy for us to model our bad bank on. |

The above analysis clearly shows that the basic task of the bad bank is to mop up the mess created by the regular banks in relation to the management of their toxic assets. The toxic assets of a regular bank are transferred to the bad bank not just for the purpose of better management of the transferred assets but also for the purpose of cleaning up the balance sheet of the regular bank. This process however involves some costs.

As long as these costs are borne by the concerned banks or private players, the impact on the economy will be limited and the government needs to have only a regulatory control over the entire process.

However, if these costs are financed with tax payer’s money, a mere regulatory control by the government agencies will not be sufficient. Rather, a more strict and watchful control of the bad banks by the government will be necessary.

In India, as of now a large number of Asset Reconstruction Companies registered under the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 are functioning. These are primarily financed by those regular banks whose toxic assets they service and liquidate. The said legislation provides the Reserve Bank of India with sufficient powers to exercise regulatory control over those bad banks.

However, it is highly doubtful, whether the said regulatory powers conferred on the Reserve Bank would be sufficient to ensure the efficient functioning of any public funded bad. More stringent legislation will be necessary.

Moreover, the economic fallout from the pandemic will further deteriorate the health of the banks. Restoring credit flow is essential to revive economic growth post the pandemic. Amid an ongoing debate on whether a bad bank will be helpful or not, the Government and the central bank have rightly considered the idea of setting up a National Bad Bank. Creation of a bad bank can go a long way in reviving credit growth and the long-halted investment cycle.

© 2025 iasgyan. All right reserved