GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES:

- Government has set a target of electric vehicles making up 30 % of new sales of cars and two-wheelers by 2030 from less than 1% today.

- National Electric Mobility Mission Plan 2020 (NEMMP) was conceived in 2013 with an objective to achieve sales of 60-70 lakh units of total EVs by 2020.

- In 2015, the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric vehicles (FAME) scheme was launched to fast-track the goals of NEMMP with an outlay of Rs. 795 crores. The initial outlay was for a period of 2 years, commencing from 1 April 2015, which was extended up to 31 March, 2019.

- FAME India Phase II has been launched, with effect from 1 April 2019, with a total outlay of Rs. 10,000 Crore over the period of three years. Emphasis in this phase is on electrification of public transportation.

- In addition to the initiatives of the Government of India, several states, including Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, have drafted EV policies to complement the national policy and address state-specific needs. Andhra Pradesh has set a target of 10 lakh EVs by 2024 while Kerala has set a target of 10 lakh EVs by 2022. Maharashtra has announced its draft EV Policy, 2018 to increase the number of registered EVs in the state to 5 lakhs. Telangana has targeted 100 per cent electric buses for intracity, intercity and interstate transport for its state transport corporation. Uttarakhand’s EV policy has focused on the manufacturing of EVs in the state with incentives for manufacturers of EVs in the MSME sector.

- National Mission on Transformative Mobility and Battery Storage was launched to promote clean, connected, shared, sustainable and holistic mobility initiatives. The Mission will drive mobility solutions that will bring in significant benefits to the industry, economy and country.

- Phased Manufacturing Programme: Valid for 5 years till 2024 to support setting up of a few large-scale, export-competitive integrated batteries and cell-manufacturing Giga plants in India.

NEED OF EVs FOR INDIA:

- Historically, mobility and fossil fuels have been inextricably linked with electric vehicles being successful only in a few niche markets. However, over the last decade, a collection of circumstances have conspired to create an opening for electric mobility to enter the mass market. Those forces include:

- Climatic change

- Advances in renewable energy

- Rapid urbanization

- Data capture and analysis: With the rise of GPS enabled smartphones and the associated universe of mobility applications, mobility has undergone a digital revolution. That digital revolution has created possibility of a greater utilization of existing transportation assets and infrastructure.

- Battery chemistry: Advances in battery technology have led to higher energy densities, faster charging and reduced battery degradation from charging

- Energy security: The petrol, diesel and CNG needed to fuel an internal combustion engine (ICE) based mobility system requires an extensive costly supply chain that is prone to disruption from weather, geopolitical events and other factors. India needs to import oil to cover over 80 percent of its transport fuel. That ratio is set to grow as a rapidly urbanizing population demands greater intra-city and inter-city mobility.

- As a result, developed economies such as EU, the USA and Japan as well as developing economies such as China and India have all included EVs in their policies to lower their carbon emissions while providing convenient and cost-effective mobility.

- In India, transport sector is the second largest contributor to CO2 emissions after the industrial sector. Road transport accounts for around 90 per cent of the total emissions in the transport sector in India (MOEF&CC, 2018).

- Given the large import dependence of the country for petroleum products, it is imperative that there be a shift of focus to alternative fuels to support our mobility in a sustainable manner.

- In India, a particular set of circumstances which are conducive to a sustainable mobility paradigm have created an opportunity for accelerated adoption of EVs over ICE vehicles. These are:

- A relative abundance of exploitable renewable energy resources.

- High availability of skilled manpower and technology in manufacturing and IT software.

- An infrastructure and consumer transition that affords opportunities to apply technologies to leapfrog stages of development.

- A universal culture that accepts and promotes sharing of assets and resources for the overall common good.

The key objectives of the EV policy are:

- Reduce primary oil consumption in transportation.

- Facilitate customer adoption of electric and clean energy vehicles.

- Encourage cutting edge technology in India through adoption, adaptation, and research and development.

- Improve transportation used by the common man for personal and goods transportation.

- Reduce pollution in cities.

- Create EV manufacturing capacity that is of global scale and competitiveness.

- Facilitate employment growth in a sun-rise sector.

CHALLENGES FOR EV IN INDIA:

- Lack of a stable policy for EV production

- Technological challenges: batteries, semiconductors, controllers, etc.

- Lack of associated infrastructural support: The lack of clarity over AC versus DC charging stations, grid stability and range anxiety are other factors that hinder the growth of EV industry.

- Lack of availability of materials for domestic production: Battery is single most important component of EVs. India does not have any known reserve of lithium and cobalt which are required for battery production.

- Lack of skilled workers.

IMPACT OF EVs:

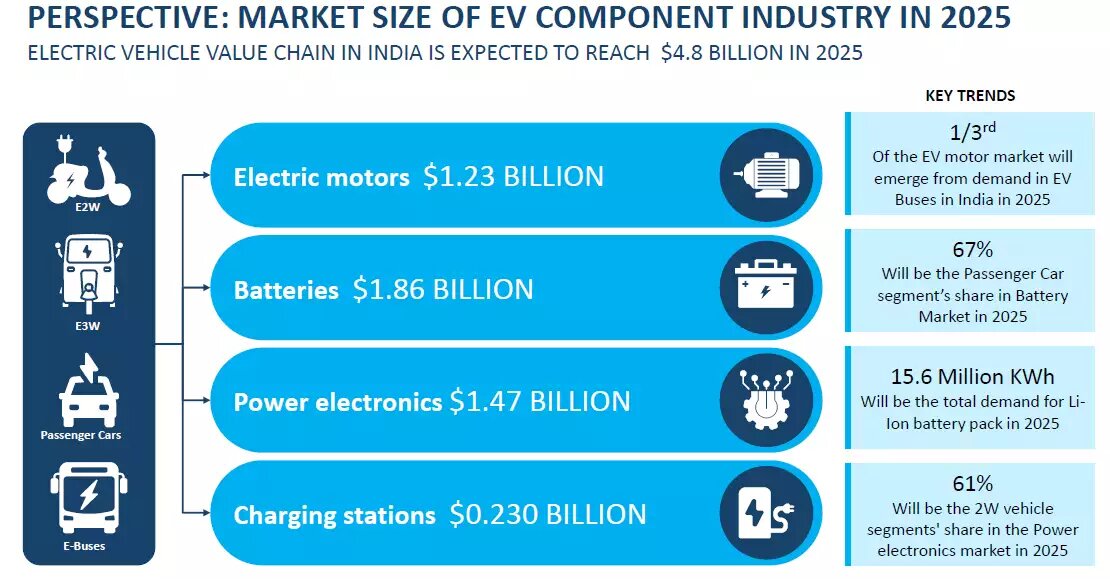

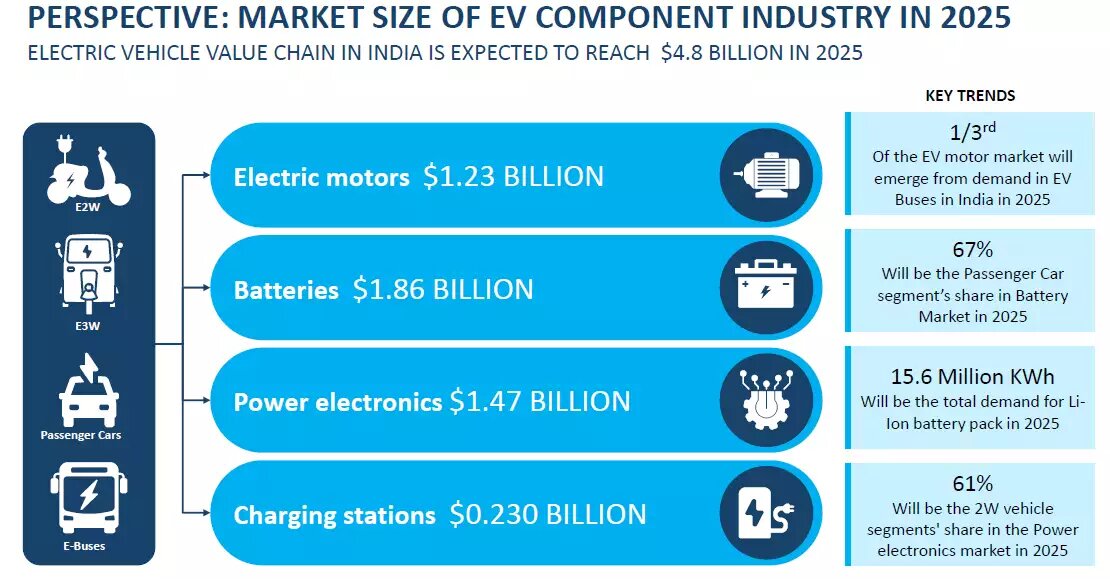

- Shifting modes of mobility could launch new business opportunities. These would emerge in areas such as charging and swapping infrastructure, service, or integrated transport. In India, energy players have entered the mobility industry, while some traditional power companies are exploring possibilities in charging infrastructure, and infrastructure companies are seen entering the battery business.

- There are several studies that suggest overall positive impact on GDP on introduction of EVs in fuel importing service dominated economies. One study has estimated that driving the shift to electric vehicles would lead to a 1% increase in EU GDP. In another study, net private and social benefits are estimated between $300 and $400 per EV.

- European Climate Foundation has estimated that through reducing oil demand by more efficient electric cars, employment will increase by 5,00,000 to 8,50,000 by 2030. Another report estimates that about 2 million additional jobs will be created by EVs by 2050.

- As far as the automotive sector is concerned, a large part of the supply chain will get transformed in the power train segment.

- Early conversion of these vehicles to electric vehicles using Lithium-ion batteries will provide clean transport to a large number of people.

- Freight movement in the rural areas, and for transport connecting farms to cities, are primarily handled by smaller transport vehicles (like rickshaws, autos and tempos). These vehicles are eminently suited for replacement by EVs.

- Sustainable mobility would require that small freight vehicles are enabled by aggregators to be made available on request, just as Uber or Ola cabs for city commuters. This would cut farm to market costs for the farmers, and also result in better fleet utilisation.

- It will have positive impact on environment and health as well.

CUSTOMIZING INDIA’S EV POLICY TO THE INDIAN AUTO-INDUSTRY TODAY:

- While India is operating in the same global context as other countries who have adopted an EV policy, it has a unique mobility pattern which other countries do not share. An EV policy for India must be tailor made to India’s particular needs.

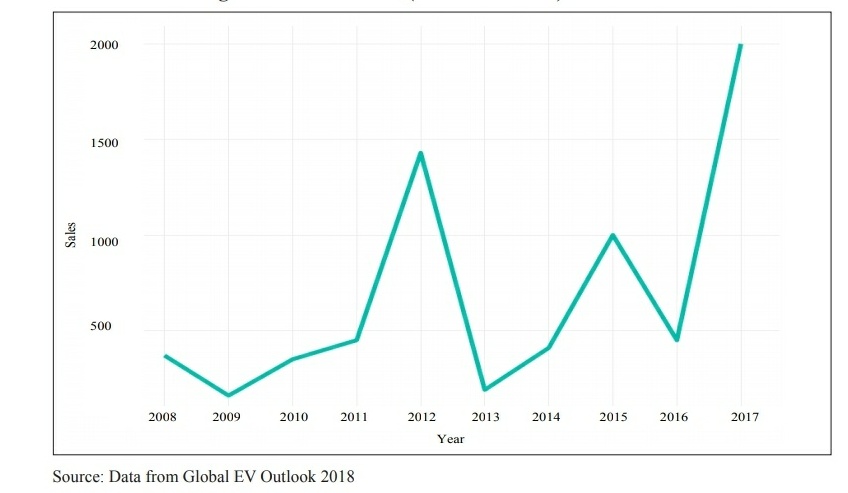

- In the near term, India should foster early adoption of vehicles by premium customers which will pave the way for consumer comfort with electrification, raise aspirations for indigenous products and make advanced technology available in the market.

- In the longer term, India should establish technological and manufacturing leadership in the economy segment of the market.

- India has an opportunity to take a leadership role in the electrification of small vehicles.

- The limiting factor of batteries on driving range may be addressed by developing an ecosystem of fast-charging or swapping of batteries.

- The general strategy should address two key variables affecting the costs of EVs: battery costs and any fiscal policies that either increase the costs of an ICE vehicle or decrease the costs of an EV.

- Broadly speaking, approaches exist to reduce battery costs – reducing the number of batteries that an electric vehicle needs and making batteries cheaper on a per kilowatt-hour basis. For the first approach, reducing the batteries needed for a given EV, there are two key pathways: 1. Providing charging infrastructure 2.Increasing efficiency of vehicles

- For the second approach, reducing the unit costs of each battery, India can explore several pathways: Selecting appropriate battery chemistries, Exploring new battery chemistries

- Beyond reducing battery costs, India can explore potential avenues of fiscal support for EVs to accelerate adoption. The standard approach in other countries to providing fiscal support to EVs has been direct subsidization. For India, however, those paths are not viable; the elimination of direct subsidy will be the policy basis. Therefore, India has to be creative to make electric vehicles and its infrastructure economically viable from the very beginning. Direct financial demand-incentives / subsidies could be replaced by Tradable Auto-Emission Coupons or credits based on CO2 emissions per km as well as on a sliding scale for vehicle efficiency.

- Keeping in mind the stage of EVs in the country, India needs a new approach to import duty while keeping “Make in India” as a goal.

- GST should favor commercial vehicles that have higher utilization and drive more KMs, to maximize electric Vehicle Kilometre (VKM).

- It is imperative that India quickly develops strong Research and Development (R&D) capacity leading to commercialization in EV subsystems.

- India would need a new power-electronics industry which can help develop and produce high-efficiency sub-systems for EV industries. A special thrust is needed to promote such industries.

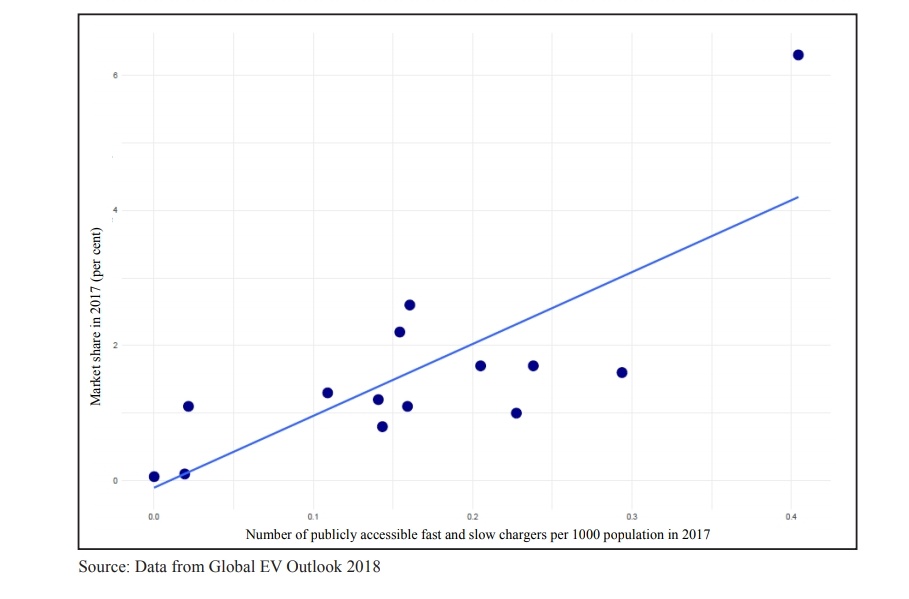

- Market share of EVs is positively related to the availability of chargers and a larger availability of chargers corresponds to a greater adoption of EVs. The market share of EVs increases with increasing availability of charging infrastructure. This is primarily due to the limited driving range of batteries in the EVs. It, therefore, becomes important that adequate charging stations are made available throughout the road networks. In India, the limited availability of charging infrastructure seems to be a major impediment to increased adoption of EVs.

- Another major impediment is that of time taken for completely charging EVs, compared to conventional vehicles. Even fast chargers can take around half an hour to charge an electric car while slow chargers could take even 8 hours. It is, therefore, an important policy issue to come up with universal charging standards for the country as a whole to enable increased investment in creation of such infrastructure.

- Also, since the battery is the heart of any EV, development of appropriate battery technologies that can function efficiently in the high temperature conditions in India need to be given utmost importance.

India has a lot to gain by converting its Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles to EVs at the earliest. Its oil-import bill would considerably reduce. ICE vehicles are a major contributor to pollution in cities and their replacement with EVs will definitely improve air quality. There is a considerable possibility that we can become leaders in small and public electric vehicles. India has over 170 million two-wheelers. If we assume that each of these vehicles uses a little more than half a litre of petrol per day or about 200 litres per year, the total amount of petrol used by such vehicles is about 34 billion litres. At ₹70 per litre, this would cost about ₹2.4 lakh crores. Even if we assume that 50% of this is the cost of imported crude (as tax and other may be 50%), one may save ₹1.2 lakh crores worth of imported oil. There is a real possibility of getting this done in the next five to seven years. This would however require innovations, a policy regime that encourages access to latest technologies and a concerted effort by the Indian industry to achieve global competition through acquiring the necessary scale and using cutting edge technology.

The country’s economy is growing and would continue to grow at a rapid pace in the coming years. This presents a great opportunity for the automobile industry as the demand for automobiles would only increase. Given the commitments that India has made on the climate front as a nation and the increasing awareness of the consumers on environmental aspects, it is likely that larger and larger share of automobile sector would be in the form of electric vehicles. According to NITI Aayog (2019), if India reaches an EV sales penetration of 30 per cent for private cars, 70 per cent for commercial cars, 40 per cent for buses, and 80 per cent for 2 and 3 wheelers by 2030, a saving of 846 million tons of net CO2 emissions and oil savings of 474 MTOE can be achieved.

It also provides us an opportunity to grow as a manufacturing hub for EVs, provided policies are supportive. While various incentives have been provided by the government and new policies are being implemented, it is important that these policies not only focus on reducing the upfront costs of owning an EV but also reduce the overall lifetime costs of ownership.