A ‘fat tax’ is a specific tax placed on foods which are considered to be unhealthy and contribute towards obesity. The tax could be placed on foods high in sugar/fat, such as crisps, chocolate and deep fried takeaways.

Thus, a fat tax is a tax or surcharge that is placed upon fattening food, beverages or on overweight individuals. It is considered an example of Pigovian taxation. A fat tax aims to discourage unhealthy diets and offset the economic costs of obesity.

The main reason behind implementing the fat tax is to make sure that people do not consume unhygienic food on large scale. The basic need of the time is to improve the health-related issues of the society and make it prosperous and healthy. The research indicates that the increase in the consumption of junk foods makes people unhealthy. A fat tax aims to decrease the consumption of foods that are linked to obesity. A related idea is to tax foods that are linked to increased risk of coronary heart disease.

It would be similar in principle to a cigarette or alcohol tax.

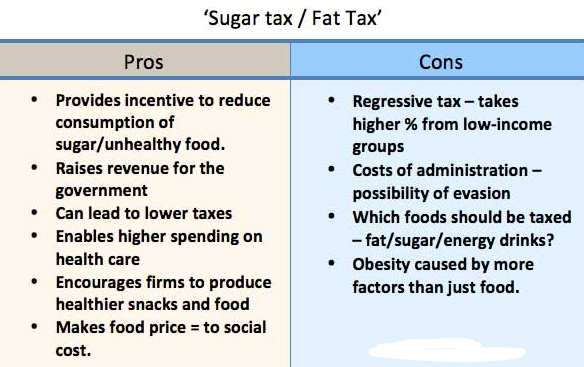

Pros of a Fat Tax

Social cost

A fat tax would make people pay the social cost of unhealthy food. Consumption of fatty foods have external costs on society. For example, eating unhealthy foods contributes to the problem of obesity. Obesity is estimated to cost the UK economy around £6.6–7.4 billion a year. (Blackwell-Synergy). These costs are due to

Those who are obese are 25% less likely to be in employment, leading to lower tax revenue and higher welfare spending on benefits. A tax on fatty foods would make people pay the social cost of these foods. Increasing the cost of unhealthy foods, would reduce demand and play a role in reducing obesity levels. Making people pay social cost would achieve a more efficient allocation of resources. (see theory of tax on negative externality)

Encourage a healthier diet

A tax on unhealthy foods would encourage people to choose healthier foods which lead to improved health and would help reduce related disease. A fat tax would also encourage producers to supply foods lower in fat and sugar. Fast food outlets would have an incentive to provide a wider range of foods.

Raise revenue. Through increasing tax on fatty foods, the government could raise substantial sums of money. They could use this revenue to offset other taxes – such as decrease the basic rate of VAT. Therefore, a fat tax could be revenue-neutral (no overall increase in tax revenue). Alternatively, the money raised from ‘fat tax’ could be used to spend treating health costs of obesity.

Equity neutral

Also, a fat tax could be equity neutral. Some may say a fat tax is regressive (takes a higher % of income from low-income families), but if other regressive taxes are reduced the overall impact on equality should be unchanged.

Similar taxes such as cigarette taxes have been widely accepted and contributed to long-term fall in cigarette smoking rates.

Food selection

Difficult to know which foods deserve a fat tax. e.g. cheese has high-fat content. Many foods could contribute to obesity if consumed in sufficient quantities.

Many factors behind obesity

Obesity is caused by more factors than just over-consumption of ‘high fat’ high sugar foods. It includes issues such as the size of portions, levels of exercise and genetic factors.

Administration costs

Administration costs in collecting tax from unhealthy foods.

Likely to be regressive

Often people on low-incomes spend a high % of their income on ‘unhealthy foods’.

Costs of obesity may be over-estimated

Obese people have lower life expectancy and so save government pension costs and health care costs in old age.

Political costs

Political costs of introducing a new tax – people dislike the idea of ‘nanny-state’ discouraging certain behaviours.

Kerala Government’s Initiative Regarding Fat Tax

In 2016, Kerala Government has imposed 14.5 percent “fat tax” on foods such as burgers, pizza .

Industry estimates suggest there are 50-75 outlets of organised fast-food restaurant chains in Kerala, including global brands McDonald's, Chicking, Burger King, Pizza Hut, Domino's Pizza and Subway. Kerala is the first state in India to introduce a "fat tax" on burgers, pizzas, doughnuts and tacos served in branded restaurants.

Fat Tax: Not a new Concept

Obesity has emerged as a global problem. According to a study published by acclaimed medical journal Lancet in 2014, India has the third largest number of obese people in the world. According to the study, India is home to 30 million obese people; if the current trends continue, this number will skyrocket to 75 million by 2025. Childhood obesity tracks into adulthood, and is an important risk factor for the development later in life of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, among others. The obesity epidemic has to do with unhealthy food, sedentary lifestyles, and loss of traditional knowledge. Given the circumstances, it is indeed laudable that Kerala has taken an initiative to tackle the problem.

The concept of a fat tax, one type of Pigovian tax, is not new. A fat tax seeks to impose restrictions on the unhealthy food regime that has emerged in the world. Japan was the first country in the world to impose a “metabo law.” This law, which included measuring citizens’ waist sizes, was sought as a tool to fight rising obesity numbers in Japan.

Similarly, in 2011 Denmark introduced a fat tax on certain products as a way to fight rising obesity and lifestyle diseases. However, after a 15-month stint the law was scrapped. The government admitted that people had been buying the same food from across the border.

Other countries such as Finland, UK, France, Hungary have imposed sugar tax on sugar-sweetened beverages.

Fat tax and its associated arguments

Fat tax has lead to discussions over its effectiveness. One of the first points of discussion has been the financial rationale behind this tax. Such a tax will not signal a shift in consumption patterns but will only add to the burden of consumers.

Another major argument relates to the fact that a fat tax on pizzas and burgers is essentially a nonstarter because such “Western” foods constitute a small part of Indian dietary patterns. India has long been a haven of spices and oil, with samosas, pakodas, and other fried items almost inevitable on Indian menus. Each of these items carry huge potential threats to the health of the population.

Others argue that Denmark’s failed experiment must be a lesson for those who seek to tax fast food. The government of Denmark’s decision to wind down the scheme within 15 months, citing administrative burdens, is a sign that such schemes are doomed to fail, critics say.

However the rationale behind this taxation is not so much to earn taxes as to create awareness about the existence of health hazards.

It is true that the Indian diet consists of a large share of unhealthy items; however, what can’t be denied is that products like pizzas and burgers have made rapid inroads into Indian markets and are poised to soon take over from traditional Indian foods.

A 2015 Delhi High Court judgement is noteworthy in this regard. The judgment, sought to ban the sale of junk food near schools. It also sought to control and regulate the advertisements of such products in schools.

Similarly, in 2019, The FSSAI banned the sale and advertising of junk food in and around 50 metres of school premises. Kitchens and canteens in schools now need a license from FSSAI to operate.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is cutting down on the sale of junk food to students whether it is in the cafeterias and canteens or in the area around schools. The sale or advertisement of unhealthy food has been prohibited inn a 50-metre radius around school premises.

Foods which are referred to as foods high in fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) cannot be sold to schoolchildren in school canteens or mess premises or hostel kitchens or within 50 metres of the school campus.

This undoubtedly shows that policymakers recognize the obesity issue and awareness is the first step toward combating it.

Fat tax would not so much as fill the government coffers as it would create awareness about unhealthy food items. In the long run, such awareness will also spread over to traditional Indian unhealthy snacks. Hence such a tax should not be opposed merely because it targets only a particular category of items.

While the Denmark experiment was a failure, there are other examples around the world in different forms which have shown such schemes are successful. For example a soft drink tax imposed by Mexico in 2014 of one peso per liter resulted in the dropping of soft drink sales by 2 percent. It also added about $2 billion to government coffers, almost a third more than what the government had anticipated.

While sales have picked up again since then, the rate of sales are nowhere near pre-taxation levels.

On the other hand, there have been successful experiments in Hungary, Finland, and France of taxing one junk food item or another. Governments worldwide are waking up to the reality of obesity and unhealthy lifestyles.

The most important component to this debate, however, is the threat to the poor. As any economist would tell us, the poor are vulnerable to false impressions of a better lifestyle, because it signals aspiration. Burgers, pizzas, and cold drinks are seen as symbols of a better lifestyle. And it is this image to which the poor are most vulnerable. In a country like India, which is confronting the poverty challenge boldly, providing a better food basket is an important part of that challenge. To effectively combat obesity, the image of fast food will have to change, from being a symbol of growth to one that is fraught with its dangers.

Research indicates that the current obesity epidemic is increasing as a result of the fast food industry expanding. Junk food outlets are changing the dietary habits of society, pushing out traditional restaurants and leading to the detrimental health effects of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. Taxes on tobacco have seen smoking rates decrease, and as a result there have been calls for fat taxes to be implemented in more countries in an attempt to reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods.

NITI Aayog has righly pointed out that India can take actions such as taxation of foods high on sugar, fat and salt and front-of-the pack labelling to tackle rising obesity in the population.

The Aayog in the report mentioned that the incidences of overweight and obesity are increasing among children, adolescents and women in India. There are many actions that India can take, such as front-of-pack labelling, marketing and advertising of HFSS foods and taxation of foods high in fats, sugar and salt. Non-branded namkeens, bhujias, vegetable chips and snack foods attract 5 per cent GST while for branded and packaged items, the GST rate is 12 per cent. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019-20, the percentage of obese women increased to 24 per cent from 20.6 per cent in 2015-16, while the percentage for men rose to 22.9 per cent from 18.4 per cent four years earlier.

To implement a fat tax, it is necessary to specify which food and beverage products will be targeted. This must be done with care, because a carelessly chosen food tax can have surprising and perverse effects.[8] For instance, consumption patterns suggest that taxing saturated fat would induce consumers to increase their salt intake, thereby putting themselves at greater risk for cardiovascular death.

Final Thoughts

As we move into a global order food habits and dietary charts will undoubtedly change. For example the consumption of pulses has rapidly fallen in India. Yet it is important to keep reinventing the food basket so that at any point it offers a healthy modicum of choices for the consumer. The fat tax should be seen as a move toward this change of perception. It is not a tool to earn revenue or rapidly shift consumer consumption patterns. It must be seen as an indicator that seeks to check and balance our dietary behavior should it reach dangerous levels.

© 2025 iasgyan. All right reserved