Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Mental Health

Mental health is a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. It is an integral component of health and well-being that underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships and shape the world we live in. Mental health is a basic human right. And it is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development.

What is a Mental Disorder or Illness?

The term ‘mental disorders’ is used to denote a range of mental, behavioural disorders and psychosocial disabilities. They are generally characterised by a combination of abnormal thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others. Mental Disorders include depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other psychoses, dementia, and developmental disorders including autism. People with mental health conditions are more likely to experience lower levels of mental well-being, but this is not always or necessarily the case.

Factors responsible

Many factors contribute to mental health problems, including:

Mental illness is an amalgamation of biological, social, psychological, hereditary, and environmental stressors.

In a nutshell,

Who Is at Risk of Developing Mental Disorders?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that the determinants of mental health and mental disorders include not only individual attributes such as the ability to manage one’s thoughts, emotions, behaviours and interactions with others, but also social, cultural, economic, political and environmental factors such as national policies, social protection, standards of living, working conditions, and community support.

Stress, genetics, nutrition, perinatal infections and exposure to environmental hazards are also contributing factors to mental disorders, says WHO.

Mental Health in India

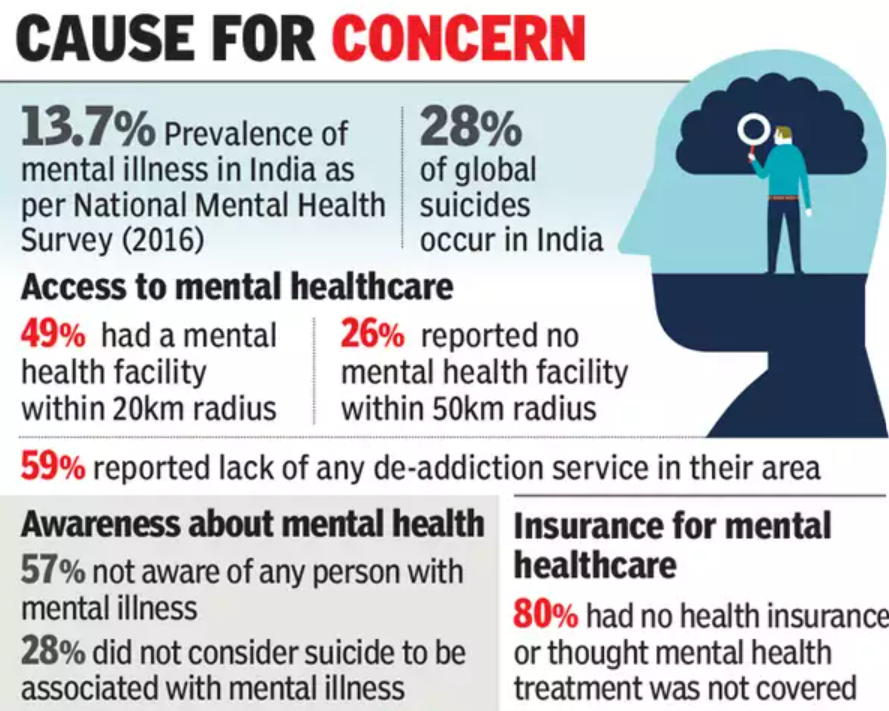

Mental disorders are now among the top leading causes of health burden worldwide, with no evidence of global reduction since 1990. The contribution of mental disorders to the total disease burden doubled between 1990 and 2017. In 2017, an estimation of the burden of mental health conditions for the states across India revealed that as many as 197.3 million people required suffer from mental health conditions. This included around 45.7 million people with depressive disorders and 44.9 million people with anxiety disorders. The situation has been exacerbated due to the Covid-19 pandemic, making it a serious concern world over.

In 2017, the President of India, Ram Nath Kovind asserted that India was “facing a possible mental health epidemic”. In the same year, 14% of India’s population suffered from mental health ailments, including 45.7 million suffering from depressive disorders and 49 million from anxiety disorders.

A study by the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative showed that the disease burden in India due to mental disorders increased from 2.5% in 1990 to 4.7% in 2017 in terms of DALYs1 (disability-adjusted life years), and was the leading contributor to YLDs (years lived with disability) contributing to 14.5% of all YLDs in the country (India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative, 2017).

As per the report, the highest contribution to DALYs due to mental disorders in India in 2017 was from depressive disorders (33.8 per cent) and anxiety disorders (19 per cent).

|

DALYs is a sum of the years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature mortality and the years lived with a disability (YLDs). Let’s assume the average life expectancy in a country is 65 years. Due to a particular disease, some people die at the age of 50 which means they are dying 15 years before they are expected to. Hence, YLLs will be 15 years. There is another disease that affects people at the age of 40 but does not lead to mortality. Here, the disease has affected the ability of a person; YLDs will be 25 years. |

The Lancet report also highlighted a substantially higher DALY rate of depressive and anxiety disorders in females than males. DALY rate of depressive disorders among females was 38.6 per cent whereas, in males, it stood at 28.9 per cent. Similarly, the DALY rate of anxiety disorders in females was reported at 21.7 per cent whereas, in males, it was at 16.2 per cent.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders, as well as eating disorders, was found to be significantly higher among women. The association between depression and death by suicide was also found to be higher among women.

World Federation of Mental Health (WFMH) Report

Concerns

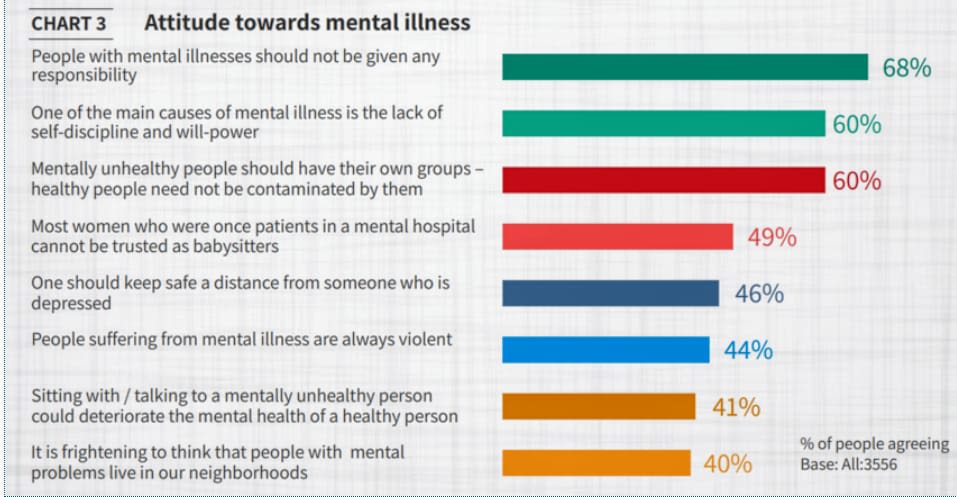

In India, having a mental health disorder is perceived with a sense of judgement and there is stigma associated with those having mental health issues (The Live Love Laugh Foundation, 2018). Mental disorders are also considered as being a consequence of a lack of self-discipline and willpower. The stigma associated with mental health as well as lack of access, affordability, and awareness lead to significant gaps in treatment. The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS), 2015-16 found that nearly 80% of those suffering from mental disorders did not receive treatment for over a year. This survey also identified large treatment gaps in mental healthcare, ranging from 28% to 83% across different mental disorders (National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS), 2016).

The Live Love Laugh Foundation Report

The Deloitte study found that 80% of India's workforce reported mental health issues during the past year. Despite these alarming numbers, the report said social stigmas around mental health issues prevented 39% of the affected respondents from taking steps to manage their symptoms.

The common symptoms of anxiousness, irritability, lack of sleep and fading memory are considered normal, especially in the Indian context. In most cases, people keep living in denial due to the lack of awareness

Economic burden of mental disorders

Mental disorders place a considerable economic burden on those suffering from them – the NMHS (2015-16) revealed that the median out-of-pocket expenditure by families on treatment and travel to access care was Rs. 1,000-1,500 per month. Discussions with respondents also revealed that expenditure incurred on treatment of mental disorders often drove families to economic hardship. This burden was more pronounced in the case of middle-aged individuals – who were also most affected by mental disorders – as it affects their productivity thereby amplifying the burden not just on the individual, but also the economy.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the economic loss to India on account of mental health disorders to be US$ 1.03 trillion. The NMHS also found that mental health disorders disproportionately affect households with lower income, less education, and lower employment. These vulnerable groups are faced with financial limitations due to their socioeconomic conditions, made worse by the limited resources available for treatment. Lack of State services and insurance coverage results in most expenses on treatment – when sought – being out-of-pocket expenses, thus worsening the economic strain on the poor and vulnerable.

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, several reports have indicated a worsening of mental health issues among individuals across age groups.

Legislation and building State capacity

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 makes several provisions to improve the state of mental health in India. This Act rescinds the Mental Healthcare Act, 1987 which was criticised for failing to recognise the rights and agency of those with mental illness.

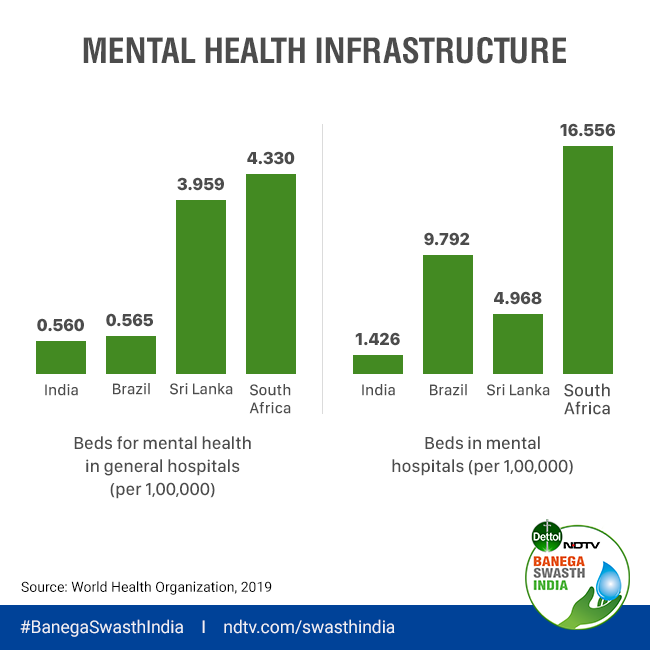

The 2017 Act states that access to mental healthcare is a ‘right’. It mandates for instituting Central and State Mental Health Authorities (SMHA), which would focus on building robust infrastructure including registration of mental health practitioners and implementing service-delivery norms. Although the Act required states to set up an SMHA in nine months of the Act being passed, as of 2019, only 19 out of 28 states had constituted an SMHA.

The National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) was introduced in 1982, in keeping with the WHO’s recommendations, to provide mental health services as part of the general healthcare system. Although the programme has been successful in improving mental healthcare access at the community level, resource constraints and insufficient infrastructure have limited its impact (Gupta and Sagar 2018).

As of 2021, only a few states included a separate line item in their budgets towards mental health infrastructure. After the passing of the Act in 2017, budget estimates for the NMHP increased from Rs. 3.5 million in 2017-18 to Rs. 5 million in 2018-19. However, this figure was reduced to Rs. 4 million in 2019-20 and has remained at the same level in subsequent years – even 2021-22 where several reports have indicated the worsening of mental health issues during the Covid-19 pandemic.

A survey by the Indian Psychiatry Society indicated that 20% more people suffered from poor mental health since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. Emerging evidence indicates that during the Covid-19 pandemic, women exhibit relatively higher levels of psychological stress among the urban poor and households with migrant workers in rural areas – who were acutely affected by the lockdown restrictions – show higher incidence of mental health issues relative to those without migrants. Students were also severely affected by the lockdowns as it required adapting to a new learning medium and environment, as well as increased concerns about future prospects. To provide psychosocial support to students during the pandemic, the government introduced an online platform, ‘Manodarpan’ – with an interactive online chat option, a directory of mental health professionals, and a helpline number.

Recently, India's Health Ministry also launched a 24-hour mental health service called Tele Mental Health Assistance and Networking Across States (Tele-MANAS). It aims to increase access to psychiatric care across the country, including in hard-to-reach areas. Callers are connected online to mental health specialists such as clinical psychologists, psychiatric social workers, psychiatric nurses or psychiatrists.

Developed countries allocate 5-18% of their annual healthcare budget on mental health, while India allocates roughly 0.05% (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2014).

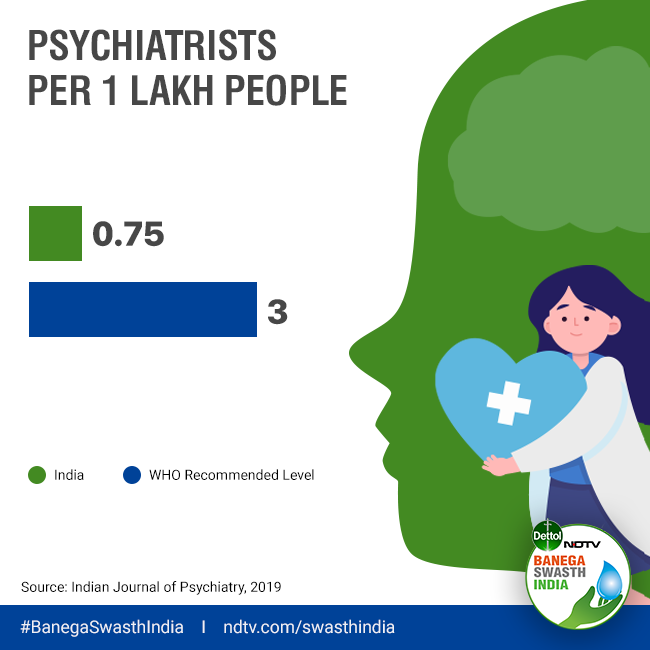

Data provided by the government of India says there are less than 4000 psychiatrists to serve the country’s population of 1.3 billion. There is about one psychiatrist for 13,000 people. Indian Journal of Psychiatry says that to fill the gap in the next 10 years we will require 2700 psychiatrists annually.

Youth-The most vulnerable population

One of India’s most valuable resources is the young people of its country, and this generation needs to be nurtured for a bright future of the nation. According to Indian Journal of Medical Research, 2018, the world includes 1.8 billion young people aged 10-24 years, and nine out of 10 live in the developing countries. India has the world's highest number of this age bracket with 356 million.

Recently concluded National Mental State Survey of India evaluated the prevalence of mental disorders within the age of 18-29 years at 7.39%. The lifelong prevalence of such disorders is 9.54%.

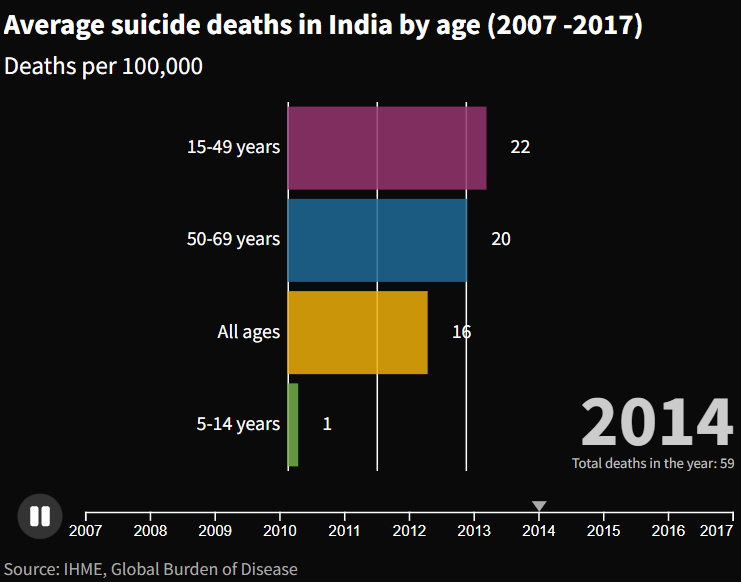

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2019, 10-20 percent of all adolescents worldwide include youngsters between 10 to 19 years experience mental disorder. In addition to that it stated suicide the second leading cause of death among 15–29-year-olds globally.

Anxiety, depression, suicide, substance abuse are the major challenges facing the youth today. Many times, youngsters cannot cope with stress and they are inclined to use various coping mechanisms such as substance abuse.

The Lancet Public Health posted that India reports 36.6% of suicides globally and it exceeded as the major cause of death among women and teenage girls from 15-19 years.

Mental health in youngsters is a major concern, primarily because they are afraid to talk about it as they fear discrimination and judgments by peers.

A big challenge is to remove the stigma and secretiveness regarding mental health which makes youngsters feel like their illness is something to be ashamed of. These things prevail mostly due to various misconceptions and lack of information and awareness in the society.

When it comes to teenage girls, they have to deal with the pressure to look perfect, behave perfectly. Not just that, they have to deal with gender-based violence, lack of financial independence, income inequality as well as socio-economic disadvantage. Females are also exposed to sexual violence which leads to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Concluding Remarks

Acknowledging the extent of the issue would be the first step towards addressing the mental health crisis in the country. The next and most pertinent step – given the socioeconomic groups largely affected by the crisis – would be to take initiative towards making mental healthcare more accessible, with targeted interventions for vulnerable groups.

It is important for everyone to be involved actively in promoting mental health awareness as well as awareness regarding the absurd stigma related to mental health. Workshops in schools, colleges, and corporations can help stimulate a movement for mental health.

Careful mapping and research need to be undertaken to produce quality data, that is essential to understand the size of the problem. This in turn should be utilised to implement a comprehensive approach, supported by heightened political commitment, scientific understanding and a citizen driven movement.

In the context of national efforts to strengthen mental health, it is vital to not only protect and promote the mental well-being of all, but also to address the needs of people with mental health conditions.

This should be done through community-based mental health care, which is more accessible and acceptable than institutional care, helps prevent human rights violations and delivers better recovery outcomes for people with mental health conditions. Community-based mental health care should be provided through a network of interrelated services that comprise:

The vast care gap for common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety mean countries must also find innovative ways to diversify and scale up care for these conditions, for example through non-specialist psychological counselling or digital self-help.

All WHO Member States are committed to implementing the “Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030", which aims to improve mental health by strengthening effective leadership and governance, providing comprehensive, integrated and responsive community-based care, implementing promotion and prevention strategies, and strengthening information systems, evidence and research. In 2020, WHO’s “Mental health atlas 2020” analysis of country performance against the action plan showed insufficient advances against the targets of the agreed action plan.

WHO’s “World mental health report: transforming mental health for all” calls on all countries to accelerate implementation of the action plan. It argues that all countries can achieve meaningful progress towards better mental health for their populations by focusing on three “paths to transformation”:

WHO gives particular emphasis to protecting and promoting human rights, empowering people with lived experience and ensuring a multisectoral and multistakeholder approach.

Talking about India specifically, offering subsidies and grants for starting clinics, hospitals, tech-enabled innovations, research, public health campaigns, and peer-based interventions is the need of the hour. Policies need to be enacted to make mental health treatment a national priority, which will then have a positive effect on tackling other ailments. Minimizing the stigma will help in not just reducing the financial burden due to mental health illness, but will also help the government to achieve its targets in other medical fields like diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypertension and cardiology, which are affected by overlooking mental health.

Mental health in India needs us to be part of a dialogue in which we are all speaking the same language.

It is time to break the silence around mental health and illness;

As Glenn Close once said, “What mental health needs is more sunlight, more candor, and more unashamed conversation.”

© 2025 iasgyan. All right reserved