POLICE REFORMS IN INDIA

BACKGROUND

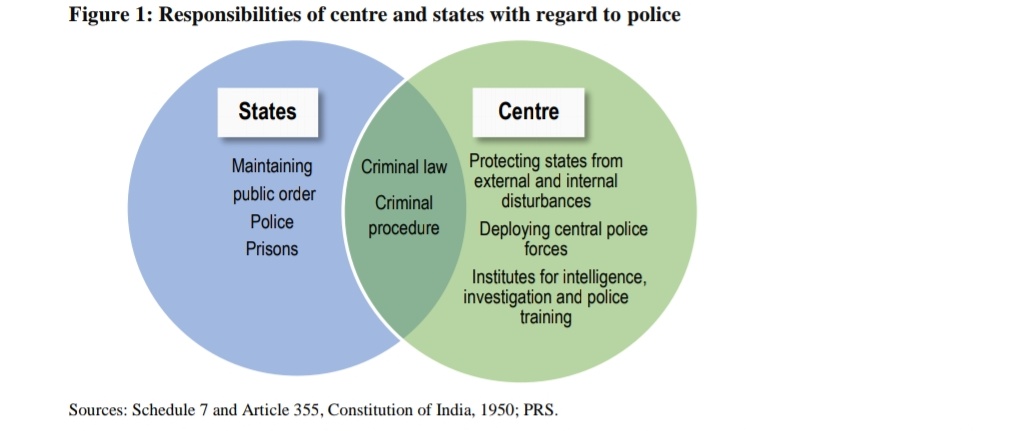

Under the Constitution, police is a subject governed by states. Therefore, each of the 29 states have their own police forces. The centre is also allowed to maintain its own police forces to assist the states with ensuring law and order. Therefore, it maintains seven central police forces and some other police organisations for specialised tasks such as intelligence gathering, investigation, research and recordkeeping, and training.

The primary role of police forces is to uphold and enforce laws, investigate crimes and ensure security for people in the country. In a large and populous country like India, police forces need to be well-equipped, in terms of personnel, weaponry, forensic, communication and transport support, to perform their role well. Further, they need to have the operational freedom to carry out their responsibilities professionally, and satisfactory working conditions (e.g., regulated working hours and promotion opportunities), while being held accountable for poor performance or misuse of power.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF CENTRE AND STATES

The Constitution provides for a legislative and executive division of powers between centre and states. The responsibilities of the state and central police forces are different. State police forces are primarily in charge of local issues such as crime prevention and investigation and maintaining law and order. While they also provide the first response in case of more intense internal security challenges (e.g., terrorist incident or insurgency-related violence), the central forces are specialised in dealing with such conflicts.

For example, the Central Reserve Police Force is better trained to defuse large-scale riots with least damage to life and property, as compared to local police. Further, the central forces assist the defence forces with border protection. The centre is responsible for policing in the seven union territories. It also extends intelligence and financial support to the state police forces.

INSIGHTS

OVERVIEW OF POLICE ORGANISATION AND FUNCTIONING

State Police Forces

Police forces of the various states are governed by their state laws and regulations. Some states have modelled their laws on the basis of a central law, the Police Act, 1861.6 States also have their police manuals detailing how police of the state is organised, their roles and responsibilities, records that must be maintained, etc.

State police forces generally have two arms: civil and armed police. The civil police is responsible for day-to-day law and order and crime control. Armed police is kept in reserve, till additional support is required in situations like riots. In this section, we discuss how civil police is organised in the country.

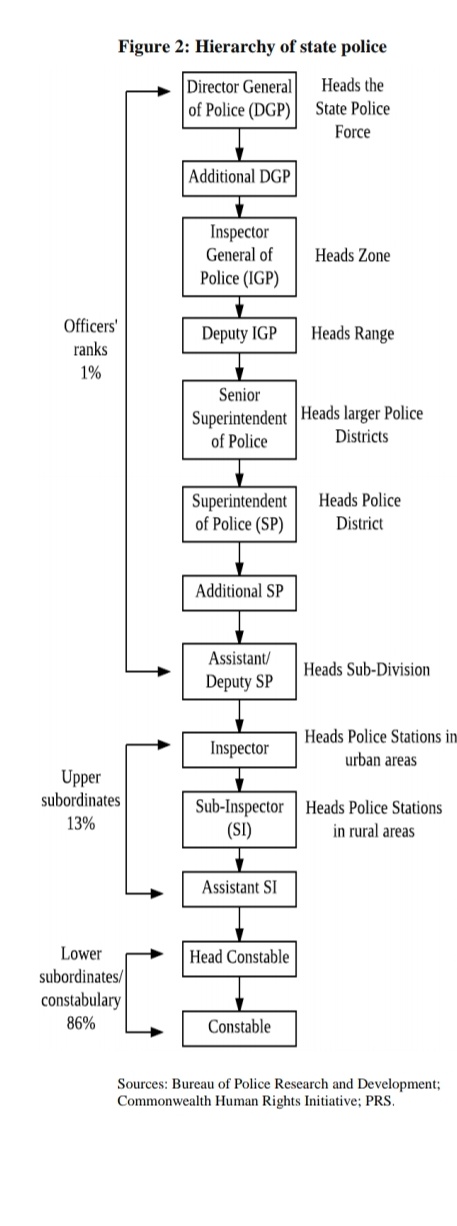

Every state is divided into various field units for the purpose of effective policing: zones, ranges, districts, sub-divisions or circles, police stations and outposts. For instance, a state will comprise of two or more zones, each zone will comprise two or more ranges, and ranges will be sub-divided into the other field units in a similar manner. The key field units in this setup are the police district and the police station.

A police district is an area declared so by the state government. It is considered the most important supervisory and functional unit of police administration because the officer in charge of the district (i.e. Superintendent of Police or SP) has operational independence in matters relating to internal management of the force and carrying out of law and order duties.

A police station (typically headed by an Inspector or Sub- Inspector) is the basic unit of police functioning. It is engaged with:

A police station may have several police outposts for patrolling and surveillance. Generally, the state government in consultation with the head of the state police force (i.e. Director General of Police or DGP) may create as many police stations with police outposts in a district as necessary, in line with the population of the district, the area, the crime situation and the work load.

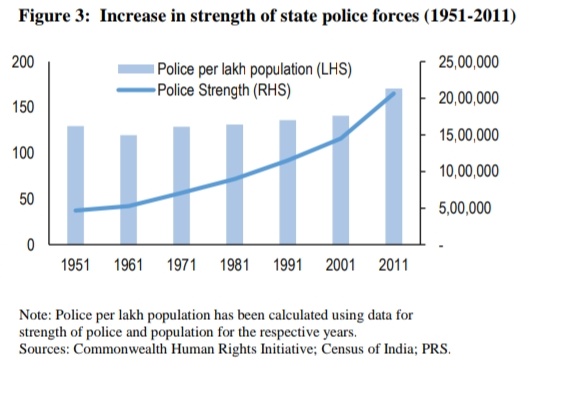

As of January 2016, the sanctioned strength of the state police forces stood at 22,80,691. Over the last six decades, the overall strength of the state forces has increased substantially. Police strength rose from 130 per lakh population to 141 per lakh population between 1951 and 2001, at an average growth rate of 2% per decade. This further increased by 21% to 171 per lakh population between 2001 and 2011.

The state government exercises control and superintendence over the state police forces. At the district level, the District Magistrate (DM) may also give directions to the SP and supervise police administration. This is called the dual system of control (as authority is vested in both the DM and SP) at the district level.

In some metropolitan cities and urban areas, however, the dual system has been replaced by the Commissionerate system to allow for quicker decision-making in response to complex law and order situations. As of January 2016, 53 cities had this system such as Delhi, Ahmedabad and Kochi.

Direct recruitment within the state police forces takes place at three levels: (i) Constables, (ii) Sub- Inspectors, and (iii) Assistant or Deputy SPs. The state governments are responsible for recruiting police personnel directly to the ranks of Constables, Sub-Inspectors and Deputy SPs. The central government recruits Indian Police Service (IPS) officers for the rank of Assistant SP. IPS is an All India Service created under the Constitution. Vacancies at other positions (as well as at the ranks of Sub-Inspector and Assistant/ Deputy SPs) may be filled up through promotions.

Training of the police forces is carried out in various kinds of state training institutes. For example, states have: (i) apex institutes to train officers (i.e., Deputy or Assistant SP and above rank personnel), (ii) police training schools for subordinate ranks and the constabulary, and (iii) specialized schools for specific police units like traffic, wireless and motor vehicle driving. In addition, some national training institutes run courses for capacity building of state forces (e.g., Central Detective Training Schools in Kolkata, Hyderabad, Chandigarh, Ghaziabad and Jaipur).

In 2015-16, states (excluding union territories) spent Rs 77,487 crore on state police forces, including on salaries, weaponry, housing and transport. Bulk of this expenditure was on revenue items, like salaries, because police is a personnel-heavy force. Expenditure on police formed 3% of the total budget for states (i.e. Rs 27,20,716 crore). On an average, in the last decade expenditure on police has been increasing at a rate of 15% per year, though the annual growth has fluctuated widely (4% in 2012-13, 30% in 2009-10).

Central Police Forces

Central Police Forces

The centre maintains various central armed police forces and paramilitary forces, of which four guard India’s borders, and three perform specialised tasks.

These are:

The total sanctioned strength of the seven central police forces is about 9.7 lakh personnel. Of these, the largest forces are the CRPF (3 lakh personnel), the BSF (2.6 lakh) and the CISF (1.4 lakh). The sanctioned strength of the central police forces (excluding the NSG, data for which was unavailable) has increased by 37% over the last decade (2006-2016). The ITBP (146% increase) and the SSB (100% increase) have experienced the maximum increase in this period.

Expenditure on the central forces has also been increasing at an average annual rate of 15% over the years (2005-06 to 2015-16). In 2015-16, the centre spent Rs 43,870 crores on the central forces, with the maximum share going to the three largest forces (CRPF: 33%, BSF: 26% and CISF: 13%).

The centre also maintains several police organisations. Key organisations include:

Police reforms has been on the agenda of Governments almost since independence but even after more than 50 years, the police is seen as selectively efficient, unsympathetic to the under privileged. It is further accused of politicization and criminalization. In this regard, one needs to note that the basic framework for policing in India was made way back in 1861, with little changes thereafter, whereas the society has undergone dramatic changes, especially in the post-independence times. The public expectations from police have multiplied and newer forms of crime have surfaced.

COMMITTEES / COMMISSION ON POLICE REFORMS

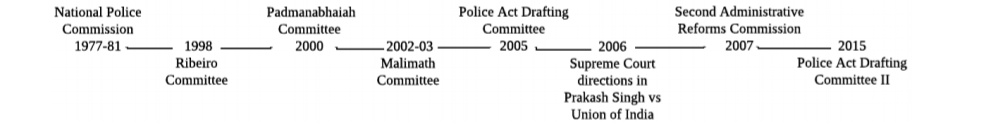

Various Committees/Commissions in the past have made a number of important recommendations regarding police reforms. Notable amongst these are those made by the National Police Commission (1978-82); the Padmanabhaiah Committee on restructuring of Police (2000); and the Malimath Committee on reforms in Criminal Justice System (2002-03). Yet another Committee, headed by Shri Ribero, was constituted in 1998, on the directions of the Supreme Court of India, to review action taken by the Central Government/State Governments/UT Administrations in this regard, and to suggest ways and means for implementing the pending recommendations of the above Commission.

Reports of The National Police Commission

The National Police Commission (NPC) was constituted in 1977 to study the problems of police and make a comprehensive review of the police system at national level. The NPC dealt with wide range of aspects of police functioning. The National Police Commission submitted eight reports during the period February 1979 to May 1981.

The major recommendations of the NPC to amend the Code of Criminal procedure 1973 were considered in the Chief Minister’s Conference on the Administration of Criminal Justice System held in 1992. Other important recommendations of NPC for revision of syllabus for IPS probationers trainees / augmentation of DCPW have already been implemented and a new Bill for regulation of private security agencies has since been passed by the Parliament and become an Act.

Reports of the Ribero Committee

On the directions of the Supreme Court of India in the case of Prakash Singh vs Union of India and others pertaining to implementation of the recommendations of the National Police Commission, the Government in 1998, constituted a Committee under the Chairmanship of Shri J.F. Ribeiro, IPS (Retd.). The Rebeiro Committee endorsed the recommendations of the NPC with certain modifications.

Report of the Padmanabhaiah Committee on Police Reforms

Government had set up a Committee in 2000 under the Chairmanship of Shri K. Padmanabhaiah, former Union Home Secretary, to suggest the structural changes in the police to meet the challenges in the new millennium. Out of 240 recommendations of the Committee, 23 recommendations regarding review of allocation of cadre policy, direct IPS officers to be given charge of district, to post IAS/IPS as judicial magistrate, police commissioners system in cities, division of NICFS, compulsory retirement to those not empanelled as DIG, review of cadre allotment policy of IPS for NE, recruitment of Constables and sub-Inspectors from the boys who have passed 10th & 12th Examination and giving them 2/3 years training in Police training Schools/Police Training Colleges respectively, maximum age of entry of IPS to be reduced to 24 years and federal offences etc were not accepted, after examination.

As many as 154 recommendations pertaining to recruitment, training, reservation of posts, involvement of public in crime prevention, recruitment of police personnel, delegation of powers to lower ranks in police, revival of beat system, use of traditional village functional village functionaries, police patrolling on national and state highways, designs of the police stations, posting and transfer of SP and above etc. were found to be such that they can be implemented without any structural changes.

Malimath Committee on Reforms in the Criminal Justice System

Government had set up (November, 2000) a Committee under the Chairmanship of Dr. (Justice) V.S. Malimath, a former Chief Justice of the Karnataka and Kerala High Courts to consider and recommend measures for revamping the Criminal Justice System. The Malimath Committee submitted its report in April, 2003 which contained 158 recommendations. These pertain to strengthening of training infrastructure, forensic science laboratory and Finger Print Bureau, enactment of new Police Act, setting up of Central Law Enforcement agency to take care of federal crimes, separation of investigation wing from the law and order wing in the police stations, improvement in investigation by creating more posts, establishment of the State Security Commission, etc.

MHA Committee to review the various recommendations and the follow up taken

The then Prime Minister, while interacting with DGPs / IGPs in 2004, appreciated the need for police reforms and declared that a Committee would be constituted to review the status of implementation of recommendations made by the various Commission/Committees. Accordingly, a Committee was constituted by MHA in December 2004 to look into this aspect.

The Committee short-listed 49 recommendations from out of the recommendations of the previous Commission/Committees on Police Reforms as being crucial to the process of transforming the police into a professionally competent and service-oriented organization. These 49 recommendations mainly pertain to:

(I) improving professional standards of performance in urban as well rural police stations,

(II) emphasizing the internal security role of the police,

(III) addressing the problems of recruitment, training, career progression and service conditions of police personnel,

(IV) tackling complaints against the police with regard to non-registration of crime, arrests, etc. and

(V) insulating police machinery from extraneous influences.

Expert Committee to draft a New Model Police Act

As one of the recommendations of Review Committee was replacement of Police Act, 1861, the Ministry of Home Affairs set up an Expert Committee (Chair: Soli Sorabjee) to draft a new Model Police Act in 2005. The Committee submitted a model Police Act in 2006.

The Model Police Act emphasized the need to have a professional police ‘service’ in a democratic society, which is efficient, effective, responsive to the needs of the people and accountable to the Rule of Law. The Act provided for social responsibilities of the police and emphasizes that the police would be governed by the principles of impartiality and human rights norms, with special attention to protection of weaker sections including minorities.

The other salient features of Model Police Act include:-

17 states (Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Punjab, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Tripura, Uttarakhand) passed new laws or amended their existing laws in light of this new model law.

Supreme Court judgment on 22.9.2006 on Police Reforms and the follow up action

The Supreme Court of India has passed a judgement in 2006– Prakash Singh and others vs UOI and others on several issues concerning Police reforms. The directions inter-alia were:

(i) Constitute a State Security Commission on any of the models recommended by the National Human Right Commission, the Reberio Committee or the Sorabjee Committee.

(ii) Select the Director General of Police of the State from amongst three senior-most officers of the Department empanelled for promotion to that rank by the Union Public Service Commission and once selected, provide him a minimum tenure of at least two years irrespective of his date of superannuation.

(iii) Prescribe minimum tenure of two years to the police officers on operational duties.

(iv) Separate investigating police from law & order police, starting with towns/ urban areas having population of ten lakhs or more, and gradually extend to smaller towns/urban areas also,

(v) Set up a Police Establishment Board at the state level for inter alia deciding all transfers, postings, promotions and other service-related matters of officers of and below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police, and

(vi) Constitute Police Complaints Authorities at the State and District level for looking into complaints against police officers.

(vii) The Supreme Court also directed the Central Government to set up a National Security Commission at the Union Level to prepare a panel for being placed before the appropriate Appointing Authority, for selection and placement of Chiefs of the Central Police Organisations (CPOs), who should also be given a minimum tenure of two years, with additional mandate to review from time to time measures to upgrade the effectiveness of these forces, improve the service conditions of its personnel, ensure that there is proper coordination between them and that the forces are generally utilized for the purposes they were raised and make recommendations in that behalf.

Out of the above seven directives, the first six were meant for the State Governments and Union Territories while the seventh directive related solely to the Central Government.

SOME ISSUES

Police accountability: Police forces have the authority to exercise force to enforce laws and maintain law and order in a state. However, this power may be misused in several ways. For example, in India, various kinds of complaints are made against the police including complaints of unwarranted arrests, unlawful searches, torture and custodial rapes. To check against such abuse of power, various countries have adopted safeguards, such as accountability of the police to the political executive, internal accountability to senior police officers, and independent police oversight authorities.

Accountability to the political executive vs operational freedom: Both the central and state police forces come under the control and superintendence of the political executive (i.e., central or state government). The Second Administrative Reforms Commission (2007) has noted that this control has been abused in the past by the political executive to unduly influence policepersonnel and have them serve personal or political interests. This interferes with professional decision-making by the police (e.g., regarding how to respond to law and order situations or how to conduct investigations), resulting in biased performance of duties.

Independent Complaints Authority: The Second Administrative Reforms Commission and the Supreme Court have observed that there is a need to have an independent complaints authority to inquire into cases of police misconduct. This may be because the political executive and internal police oversight mechanisms may favour law enforcement authorities, and not be able to form an independent and critical judgement district level complaints authorities.

Of 35 states and UTs (excluding Telangana), two states had not made laws or issued notifications regarding setting up of the police complaints authorities (i.e., Jammu and Kashmir and Uttar Pradesh) as of August 2016. A report of the NITI Aayog also shows that the composition of these authorities is at variance with the Model Police Act, 2006 and the Supreme Court directions.

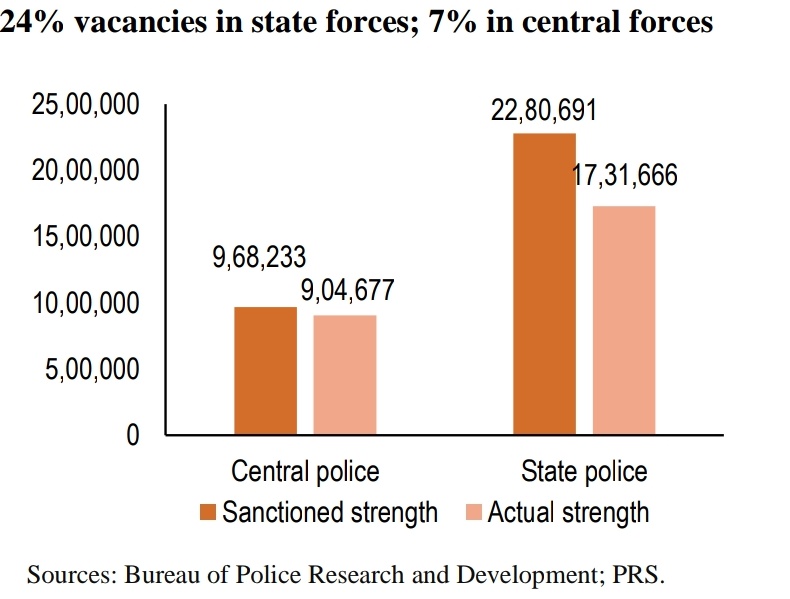

Vacancies and an overburdened force: Currently there are significant vacancies within the state police forces and some of the central armed police forces. As of January 2016, there were 24% vacancies (i.e. 5,49,025 vacancies). States with the highest vacancies in 2016 were Uttar Pradesh (50%), Karnataka (36%), West Bengal (33%), Gujarat (32%) and Haryana (31%).

The total sanctioned strength of the seven central police forces was 9,68,233. 7% of these posts (i.e. 63,556 posts) were however lying vacant. Sashastra Seema Bal (18%), Central Industrial Security Force (10%), Indo-Tibetan Border Police (9%) and National Security Guards (8%) had relatively high vacancies. Vacancies in the central police forces have been in the range of 6%-14% since 2007. A high percentage of vacancies within the police forces exacerbates an existing problem of overburdened police personnel.

While the United Nations recommended standard is 222 police per lakh persons, India’s sanctioned strength is 181 police per lakh persons.8After adjusting for vacancies, the actual police strength in India is at 137 police per lakh persons. Therefore, an average policeman ends up having an enormous workload and long working hours, which negatively affects his efficiency and performance.

Constabulary related issues: Qualifications and training, Housing.

Crime investigation: In India, crime rate has increased by 28% over the last decade, and the nature of crimes is also becoming more complex (e.g., with emergence of various kinds of cybercrimes and economic fraud). Conviction rates (convictions secured per 100 cases) however have been fairly low. Law Commission has observed that one of the reasons behind this is the poor quality of investigations. Crime investigation requires skills and training, time and resources, and adequate forensic capabilities and infrastructure. However, the Law Commission and the Second Administrative Reforms Commission have noted that state police officers often neglect this responsibility because they are understaffed and overburdened with various kinds of tasks. Further, they lack the training and the expertise required to conduct professional investigations. They also have insufficient legal knowledge (on aspects like admissibility of evidence) and the forensic and cyber infrastructure available to them is both inadequate and outdated.

Police infrastructure: Modern policing requires a strong communication support, state-of-art or modern weapons, and a high degree of mobility. The CAG and the BPRD have noted shortcomings on several of these fronts.

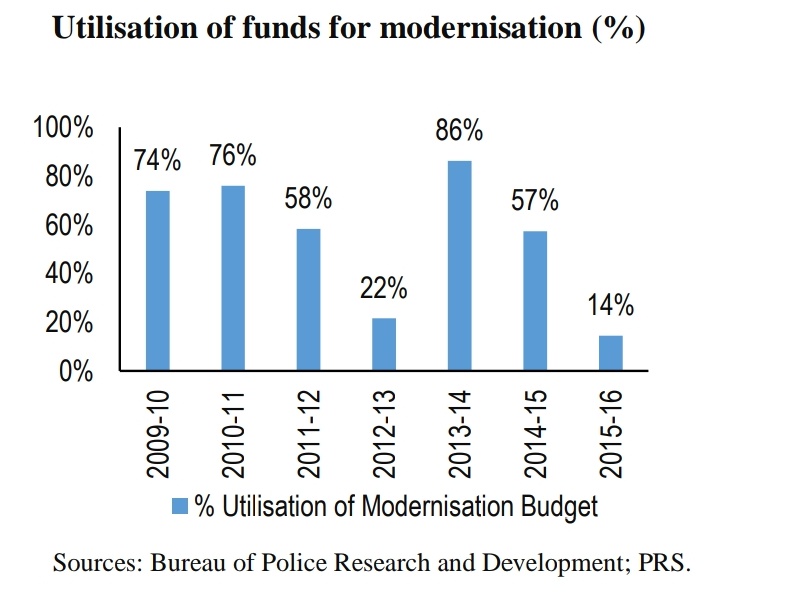

Underutilisation of funds for modernisation: In 2015-16, the centre and states allocated Rs 9,203 crore for modernisation. However, only 14% of it was spent.

Police-public relations: Police requires the confidence, cooperation and support of the community to prevent crime and disorder. For example, police personnel rely on members of the community to be informers and witnesses in any crime investigation. Therefore, police-public relations is an important concern in effective policing. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission has noted that police-public relations is in an unsatisfactory state because people view the police as corrupt, inefficient, politically partisan and unresponsive.

One of the ways of addressing this challenge is through the community policing model. Community policing requires the police to work with the community for prevention and detection of crime, maintenance of public order, and resolving local conflicts, with the objective of providing a better quality of life and sense of security. It may include patrolling by the police for non-emergency interactions with the public, actively soliciting requests for service not involving criminal matters, community-based crime prevention and creating mechanisms for grassroots feedback from the community. Various states have been experimenting with community policing including Kerala through ‘Janamaithri Suraksha Project’, Rajasthan through ‘Joint Patrolling Committees’, Assam through ‘Meira Paibi’, Tamil Nadu through ‘Friends of Police’, West Bengal through the ‘Community Policing Project’, Andhra Pradesh through ‘Maithri and Maharashtra through ‘Mohalla Committees’.

© 2025 iasgyan. All right reserved