The Government of India (GoI) has set ambitious renewable electricity targets for the short to medium term. By 2022 the country aims to have 175 GW of installed renewable electricity capacity. In 2018 the GoI announced an increased ambition of 227 GW renewable capacity by 2022 and 275 GW by 2027. At the United Nations’ Climate Summit in New York on 23 September 2019, the Prime Minister of India announced a new target of 450 GW of renewable electricity capacity, without specifying a date.

At the end of November 2019 grid-connected renewable electricity capacity reached 84 GW, with 32 GW coming from solar photovoltaic (PV), around 37 GW from onshore wind and the remainder from small hydro. To ensure continuous progress in the growth of renewables, auction design, grid connections and the financial health of the power distribution companies (DISCOMs) are critical elements for reform.

Modern renewable energy is not only used in electricity generation – the potential is also great for heating, cooling and transport. India needs a holistic strategy for renewable energy to tap into this potential and to make sure that market development can be beneficial for sustainable development more generally, including local air and water quality. Potential also exists to scale up the use of bioenergy, including energy-from-waste (EfW), which requires robust sustainability governance.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND TRENDS

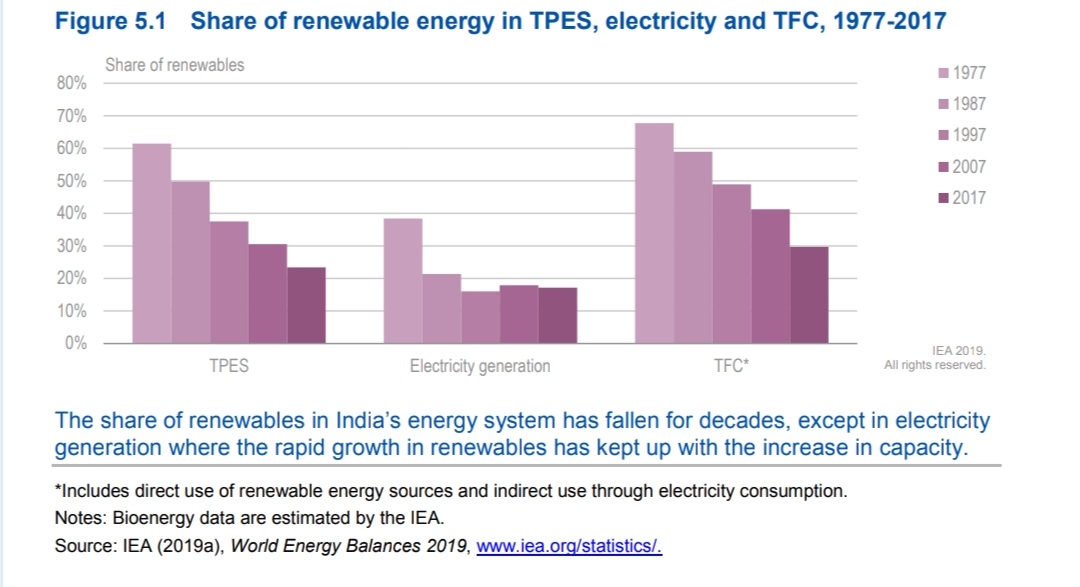

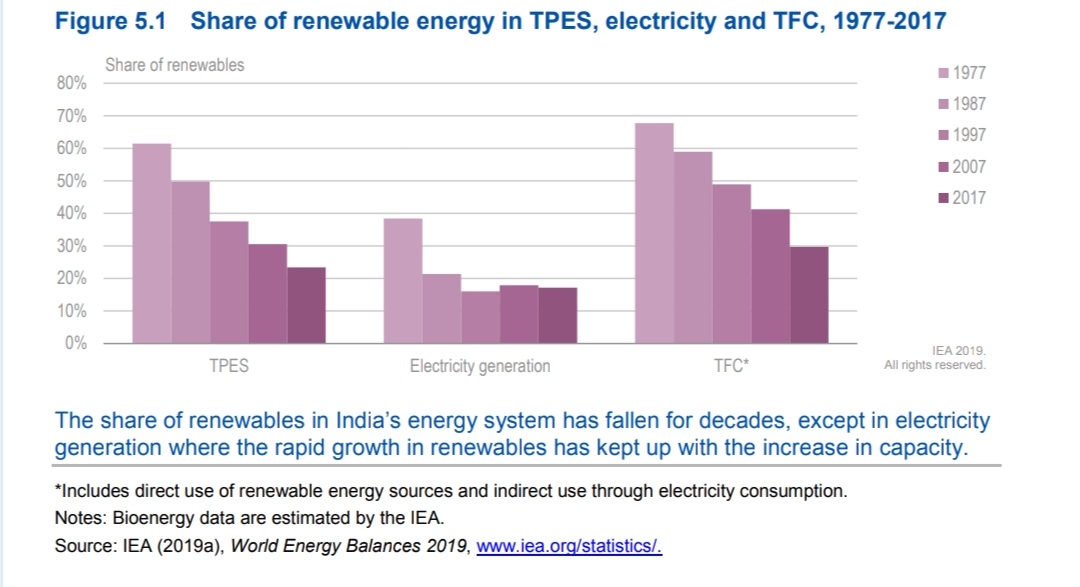

Renewable energy in India has long been dominated by traditional use of biomass in the residential sector. However, in recent years the country has rapidly expanded its use of renewable power sources. This has kept the share of renewables in electricity generation stable at around 16% over the last decade amid strongly increasing electricity consumption, although the share of fossil fuels in total primary energy supply (TPES) and total final consumption (TFC) has significantly increased since the 1970s.

RENEWABLE ENERGY IN TPES

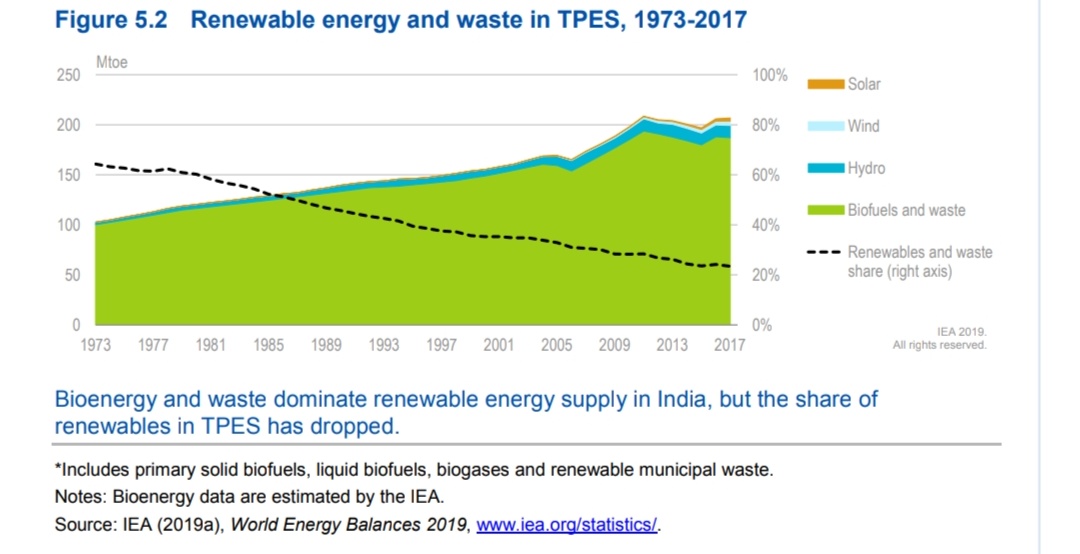

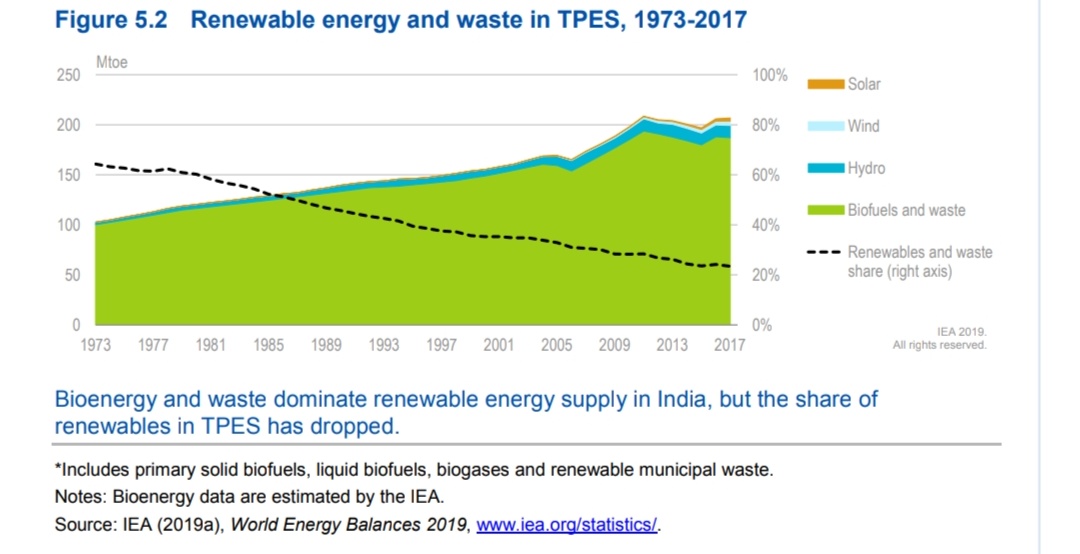

Traditional use of biomass for heating and cooking in households is by far the largest source of renewable energy in India. Bioenergy consumption has increased steadily with population growth for decades, albeit at a slower rate than overall energy supply. Thus, the share of renewables in TPES has been declining over time, despite a recent increase in renewable power generation from hydro, wind and solar photovoltaic (PV). In 2017 the total supply of renewable energy was around 200 Mtoe, representing 23% of TPES.

ELECTRICITY FROM RENEWABLE ENERGY

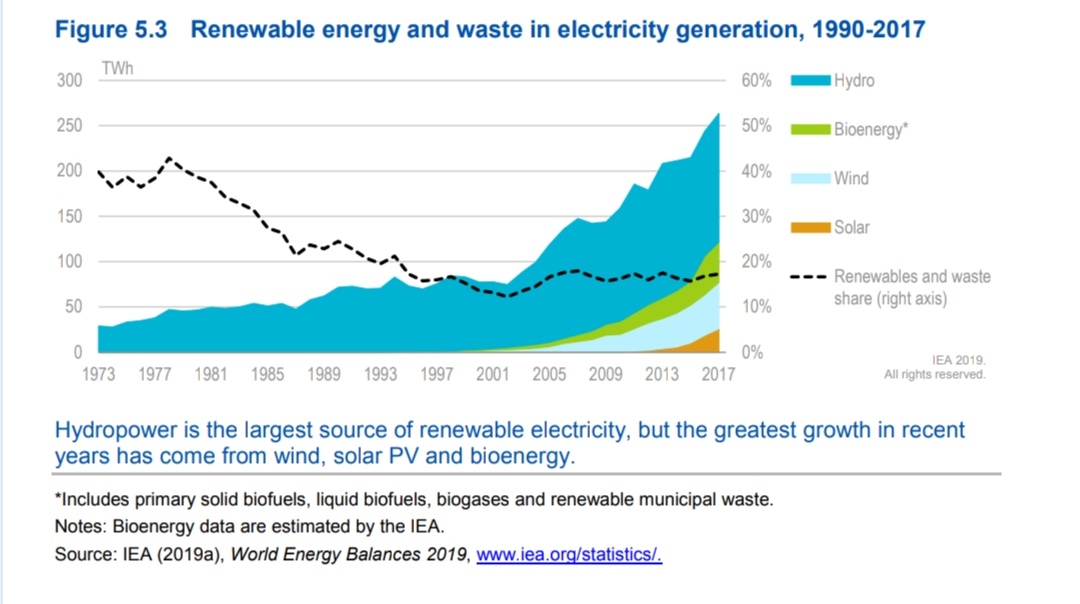

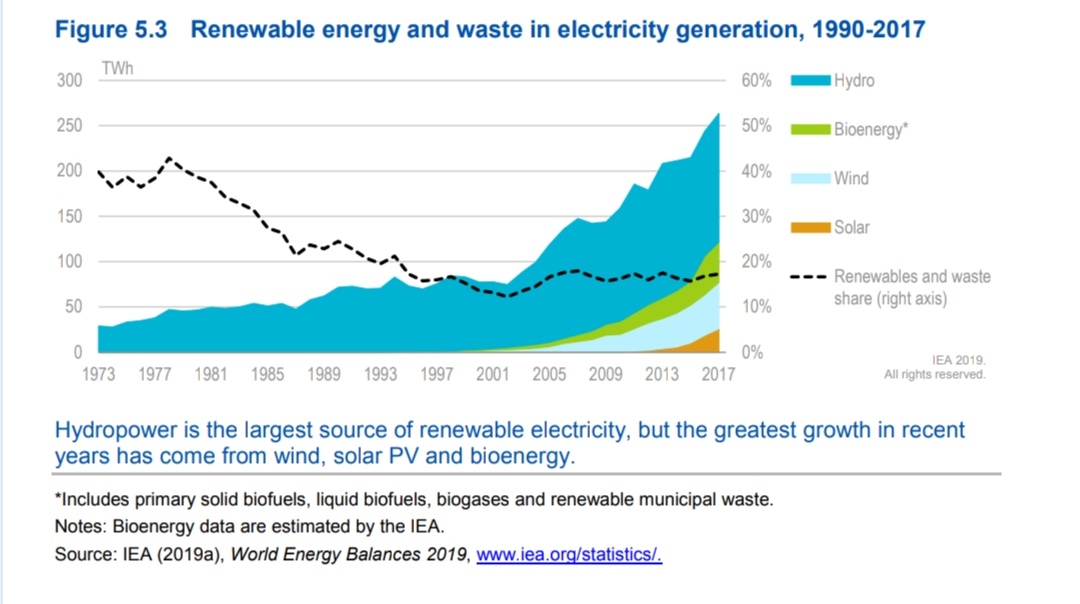

Although traditional use of bioenergy represents the largest supply of renewable energy, the most dynamic development is in the electricity sector, with renewable electricity generation from a range of technologies including hydropower, wind, solar and bioenergy.

Hydropower has been the dominant source of renewable electricity in India for a long time. In the late 1970s hydropower alone accounted for around 40% of total electricity generation. Although the supply of hydropower has increased steadily, its share of electricity generation has fallen to around 10%. In the last decade very strong growth in electricity from wind, solar PV and bioenergy has maintained the total share of renewables stable around 16-17%.

Wind power generation has increased at an average annual growth rate of 14% in the ten years 2007-16, accounting for 3.3% of total electricity generation in 2017. Solar power has only started to grow in the last few years, supported by the 2022 target and auctions for new PV installations. In the five years 2013-17, solar power generation increased by 64% per year on average.

Bioenergy is also increasing in power generation. The principal source is co-generation units using bagasse residues from India’s large sugar industry. Using biomass for power generation is a more sustainable use of bioenergy resources than the traditional use in households.

A minor share of electricity comes from EfW projects using urban, industrial and agricultural wastes and residues. EfW can provide energy at the point of demand and support the waste management sector in India. Increasing urbanisation and economic growth present pressing waste management challenges for cities and therefore potential exists for further development of the EfW sector.

INSTITUTIONS

- The dedicated Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) is in charge of the development of policies for renewables in electricity, transport and heat in India. The MNRE contains the National Institute of Solar Energy and the National Institute of Wind Energy, undertaking activities related to R&D, testing, certification, standardisation, skill development, resource assessment and awareness. The MNRE also covers bioenergy for electricity, including EfW, and biogas.

- The Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) under the MNRE functions as a non-banking financial institution for providing loans for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects.

- Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) is responsible for implementing various MNRE subsidy schemes, such as the solar park scheme and the grid-connected solar rooftop scheme. SSS-NIRE is an autonomous institution of the MNRE, an emerging R&D centre with a mandate to focus on bioenergy and develop innovative technologies in the area of renewables and biofuels.

- The Ministry of Power (MoP) governs the electricity sector in India, including renewables for power generation. The Minister of Power has also oversight of the MNRE and is in charge of renewable energy. As an agency of MoP, the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) is the main advisor to the MoP and is responsible for the technical co-ordination and supervision of programmes, including drafting the National Electricity Plan. The MoP is also responsible for the Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY) programme, which aims to improve the financial health and operational efficiency of India’s debt-ridden DISCOMs.

- The Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) regulates the tariffs for generation companies and transmission utilities, and grants licences for interstate transmission and trading.

- The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG) is the overall co-ordinating ministry for the development of biofuels and implementation of national biofuels policy. The MoPNG manages the marketing and distribution of biofuels, blending levels, pricing and procurement policy, and capacity building.

- The Ministry of Science and Technology (Department of Biotechnology and Department of Science and Technology) has responsibility for innovation and has a strong focus on bioenergy technology research.

POLICY AND REGULATION

- Electricity: The government has a target to achieve 175 GW of grid-connected renewable electricity by March 2022: 100 GW solar, 60 GW wind, 10 GW biomass and 5 GW of small hydropower. In addition, the MNRE is targeting 1 GW of geothermal capacity by 2022. The 2018 National Electricity Plan sets out ambitions to achieve 275 GW of renewables by 2027, which would increase their share to an estimated 44% of installed capacity and 24% in electricity generation.

- Utility-scale renewables: For utility-scale renewables India relies on renewable purchase obligations (RPOs), renewable electricity certificates (RECs), accelerated depreciation of renewable energy assets for commercial and industrial users, and most recently on competitive tenders.

- The RPOs require DISCOMs, energy producers and certain consumers to obtain a share of their electricity from renewable sources. Determination of RPO trajectories and monitoring of compliance are carried out by the State Electricity Regulatory Commissions. In June 2018 the RPO requirement was raised from 17% to 22%, with 10.5% from solar, up from 6.75%, and 10.5% from non-solar renewable sources by 2022, up from 10.25%.

- The RECs are used by the obligated entities to meet their RPO requirements. The CERC established voluntary RECs in 2010 and allowed their trading in March 2011 to address the discrepancy between the availability of electricity from renewable sources across the regional markets and the demand from obligated utilities and customers to meet their RPOs under the Electricity Act 2003. The REC programme is enforced by the CERC.

- The accelerated depreciation tax benefit for renewable energy plant developers was reestablished in 2014 after a two-year long gap and was fixed at an 80% level until March 2017. As of 1 April 2017 the benefit was lowered to 40%. Users of renewable energy can depreciate their investment in a renewable energy plant at a much higher rate than general fixed assets and can claim tax benefits on the value depreciated in a given year.

- In order to reach the 2022 target, the government launched various competitive auctions.

- Rooftop solar PV: For residential and commercial solar PV applications, the GoI has set an ambitious target of 40 GW of rooftop solar by 2022 within the 100 GW solar target. The MNRE has adopted guidelines for the implementation of Phase II of its Grid-Connected Rooftop Solar Programme. The MNRE has several policies to incentivise and facilitate rooftop installations: a) providing central financial assistance for residential, institutional, social and government buildings; b) advising states to implement net/gross metering regulations and tariff orders; c) providing a model memorandum of understanding, power purchase agreement (PPA) and CAPEX agreement for rooftop projects in the government sector; and d) appointing experts to support public-sector undertakings in the implementation of rooftop projects in ministries and departments. In February 2019 the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) approved financial support totalling USD 6.5 billion by 2022 to promote the use of solar among farmers.

- Offshore wind: The GoI estimates the potential of offshore wind to be in the region of 10-20 GW. A good alternative to onshore wind, offshore wind, however, has yet to be adopted in India. An initial tender of 1 GW is expected to be held and a white paper is being developed in collaboration with the European Union to identify bottlenecks in the supply chain and industry infrastructure, as India does not have a large-scale offshore turbine industry.

- Off-grid solar PV: Various schemes are available at both national and state level to support the uptake of offgrid electrification, mainly through solar technologies. In 2015 the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY) scheme was launched to support the adoption of decentralised distributed electricity in rural India via off-grid installations, mainly mini-grids. In 2017 the Off-Grid and Decentralised Solar PV Programme was put in place to facilitate uptake of various solar PV applications for lighting and water pumping in rural areas by providing financial means to the implementing agencies. The programme was extended until the end of the 2020 financial year. In December 2018 the Atal Jyoti Yojana (AJAY) Phase II programme was initiated to finance the installation of over 3 million solar street lights in selected regions. Initiated by the GoI in February 2019 (and followed by guidelines in July 2019), the KUSUM scheme will support farmers to replace existing diesel pumps with solar PV pumps (with both on-grid and off-grid features). The scheme will allow farmers to become prosumers and sell power to the DISCOMs at a predetermined price. The scheme aims to add solar and other renewable capacity of 28 GW by 2022. It has three main components: a) financing of 10 GW of renewable energy plants, each up to 2 MW capacity; b) offering 1.75 million standalone solar agriculture pumps, central government to provide 30% subsidy and state government to provide 30% subsidy; and c) converting 1 million grid connected agriculture pumps to solar powered operation with central government and state government providing 30% subsidy each.

- Bioenergy and waste: India is close to meeting its 2022 target for 10 GW of bioenergy capacity. The principal contributor is the use of bagasse in sugar mill co-generation plants. The Scheme to Support Promotion of Biomass-Based Co-generation in Sugar Mills and Other Industries offers central financial assistance in the form of a capital subsidy per additional MW of capacity delivered by investment in more efficient co-generation technology and runs until 2020. India has also introduced a policy to instigate low-level biomass co-firing (5-10%) in appropriate power generation facilities. India’s 2016 waste management rules provide the basis for stimulating greater exploitation of EfW.

BARRIERS TO INVESTMENT IN RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS

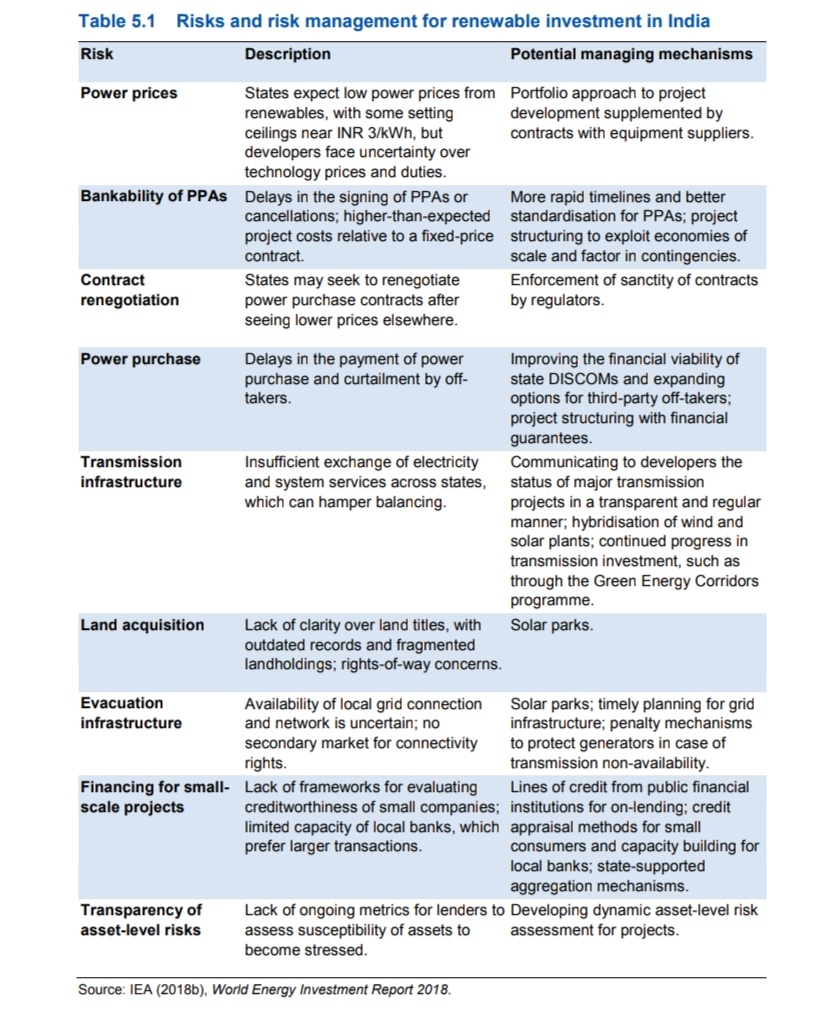

- Besides permitting and network expansion delays, the key barriers to investment in renewable energy projects in India are the small transaction size for distributed energy projects, the credit rating of the off-taker, the absence of clear business models for rooftop solar and the disaggregated nature of the market.

- India’s DISCOMs are at the forefront of investing in solar PV. However, their financial viability as off-taker has come under pressure because of poor payment discipline, high commercial and technical electricity losses and consequent financial losses, cross-subsidised electricity prices that do not cover costs, and a lack of metering and billing.

- In 2015 the GoI adopted the UDAY scheme, which seeks to alleviate high debt and interest cost burdens on DISCOMs and has improved their financial health since its introduction. However, its impact varies considerably across states. At least 40% of capacity additions needed to meet India’s 2022 solar PV target are allocated to states with DISCOMS that have below-average to very low operational financial performance, according to government ratings (B-C grade).

- Financing decentralised projects, such as solar irrigation pumps, rooftop solar and minigrids, is often more difficult than funding utility-scale projects despite the very large markets for these products.

- Local banks have limited capacity and tend to prefer the larger transaction sizes associated with utility-scale projects.

- Moreover, there is a lack of frameworks for evaluating the creditworthiness of smaller companies and consumers.

- For tenders carried out by the central government, the payment security mechanism provided by the SECI was seen as supportive, but there are some concerns over its operation in practice.

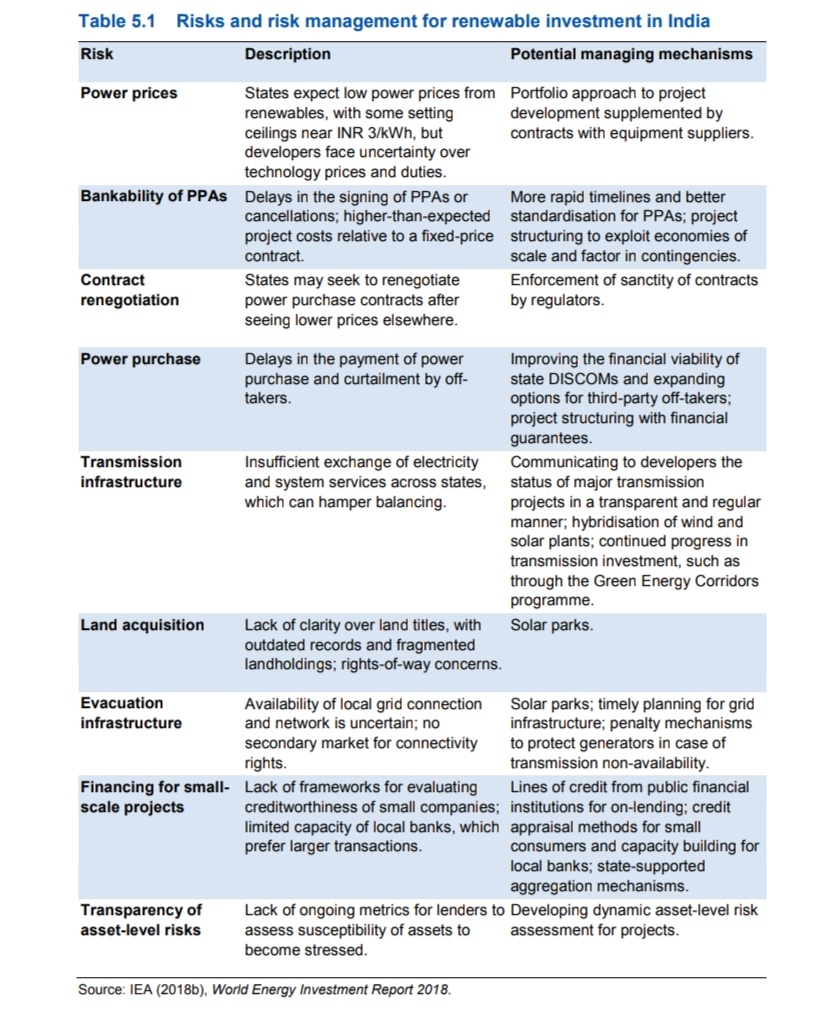

- The risks facing renewable investments generally fall into two categories: project development risks; and operational risks. These pose challenges to investments where they reduce the availability of financing, elevate the cost of capital or delay project development.

GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES IN RECENT TIMES

- The Green Energy Corridors project started in 2013 to establish dedicated grid infrastructure to connect resource-rich states and enable intra- and interstate transmission to load centres.

- The government’s recent policy to facilitate solar–wind hybrid plants, which can include battery storage, may help to better optimise transmission infrastructure and balancing the needs of variable renewables.

- Under its solar parks scheme, the central government provides financial support to the states to facilitate bringing parcels of land and supporting infrastructure together in a simplified process.

- In 2018 the MoPNG introduced a new biofuels policy covering both conventional and advanced biofuels. The new policy proposes an indicative target of 20% ethanol blending in gasoline and 5% biodiesel blending in diesel by 2030.

- The National Biogas and Manure Management Programme set a target for 65 and 180 biogas plants in 2017/18. A programme to promote off-grid and decentralized concentrated solar thermal (CST) technologies for community cooking, process heat and space heating and cooling applications in industrial, institutional and commercial establishments was extended in February 2018 to run until 2020.

- At the end of 2018 around 300 MW of EfW capacity had been installed, and the country’s largest plant (24 MW) was commissioned in New Delhi in 2017.

- The GoI promotes the use of urban, industrial and agricultural waste and residues with a programme providing financial assistance in the form of capital subsidy and grants, with a target of 57 MW equivalent capacity for the period 2017/18 to 2019/20.

- The MNRE has partnered with the United Nations Development Programme to promote clean energy use for small businesses and industries under the Access to Clean Energy for Rural Productive Uses programme. It aims to enhance the use of reliable and affordable renewable energy for rural productive uses, providing livelihoods in areas in the states of Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha.

- The country’s Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) for waste involves using refuse-derived fuel from urban areas within a specified distance from cement plants, and it anticipates that alternative fuels could generate almost 19% of the cement industry’s thermal energy demand by 2030.

ASSESSMENT

- India has emerged as a global leader in renewable energy, notably in solar power. By end of November 2019 grid-connected renewable electricity capacity had reached 84 GW, including 32.5 GW from solar PV and around 37 GW from onshore wind as well as small hydro.

- The ambitious targets have spurred unprecedented growth in solar PV and wind in the country and has gone hand in hand with increased international engagement, including the establishment of the International Solar Alliance. In addition, modern bioenergy use in power generation and industry has been expanding rapidly.

- India has put in place a number of important policies that have underpinned recent strong expansion of renewables.

- However, it will need to further strengthen policy action and accelerate policy implementation to address a number of barriers that still hamper renewables deployment.

- Among the main investment barriers and risks to renewable electricity growth in India are the financial health of DISCOMs, weak transmission and distribution grid infrastructure and difficulties in permitting and land acquisition.

- According to IEA data, bioenergy and waste is the largest source of renewable energy in India’s primary energy supply (21% of TPES, the third-largest energy source in India). However, more than two-thirds of India’s bioenergy consumption comes from traditional use of biomass in the residential sector resulting in negative environmental and health impacts.

- India has historically struggled to meet its 5% ethanol blending mandate and biodiesel is at an early stage of development, as there is no formal mandate. Increased fuel ethanol production would support the financial health of sugar mills while also displacing a higher share of gasoline demand – which is anticipated to grow at approaching 10% per year over the next five years – with a lower-carbon alternative. Therefore, using domestically produced ethanol is viewed as a means to offset oil demand, in line with the aim of reducing crude oil imports by 10% by 2022.

- Despite pressing waste management challenges from urbanisation, population and economic growth trends, EfW activity (in the form of municipal solid waste plants) is very low. Over the longer term, the robust implementation of the 2016 waste management rules should spur uptake. The use of EfW plants with controlled high-temperature combustion and pollution control technology is a superior solution to landfills, as it can generate electricity for cooling or heating purposes through combined heat/cooling and power generation.

- Many sugar mill co-generation systems in India operate at relatively low efficiency because the low-pressure backpressure steam turbines commonly used are designed to produce steam at the pressure required for on-site processes. The level of electricity generation in these systems is not optimised, however, and consequently the full energy potential of bagasse resources is not exploited. Transitioning to higher-pressure co-generation systems is therefore a key way to increase surplus energy production.

WAY FORWARD

The Government of India should:

- Develop a holistic strategy on renewable energy, encompassing both supply and use, for electricity, heating and cooling as well as transport to fully harness India’s large untapped potential.

- Adapt the design of competitive auctions by SECI to ensure India can meet the 2022 renewable electricity targets by:setting out annual procurement trajectories, strengthening pre-qualification criteria, adjusting the price caps to ensure commercial viability of high-quality projects, mitigating all project-related risks.

- Adopt a medium- to long-term target for renewable electricity for the period beyond 2022 to give investors certainty.

- Support further growth of distributed renewable energy – notably the solar PV rooftop market – by strengthening and clarifying incentives to implement business models that offer customers standardised solar PV rooftop systems, based on international and national best practice experience.

- Ensure compliance with RPOs imposed by state regulators.

- Strengthen the financial viability of DISCOMs by ensuring the full implementation of the UDAY scheme.

- Maximise India’s significant potential for sustainable bioenergy, comprising implementation of the policy on transport biofuels to scale up conventional and advanced biofuel production while ensuring sustainability criteria are met, realising the potential to scale up bioenergy in the sugar and cement industries, and scaling up EfW, using best practice throughout the supply chain.