Description

Copyright infringement not intended

In News

- New Adoption rules create confusion over the implementation of the provision that requires the transfer of adoption petitions from courts to District Magistrates (DMs).

- Social activists, Parents, and adoption agencies have raised concerns that it could lead to further delays in the adoption procedure.

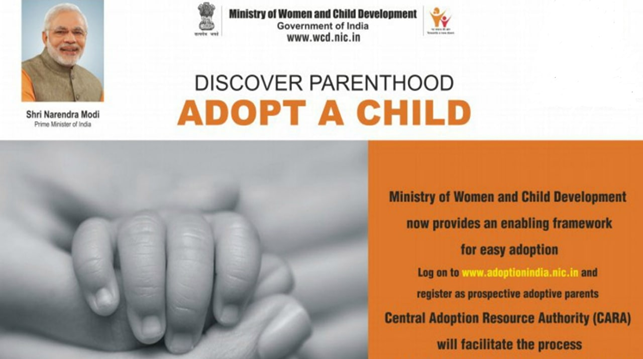

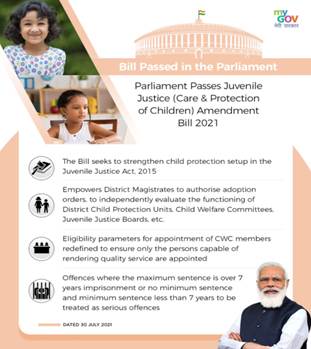

- Last year, the Indian Parliament passed the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Amendment Act, 2021, which empowers DMs to give adoption orders.

- The amendments came into effect on 1st September 2022.

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Amendment Act, 2021

- The Bill amends the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act of 2015.

- The amendment Act contains provisions related to children in conflict with the law and children in need of care and protection.

- The Act provides that the Juvenile Justice Board will inquire about a child who is accused of a serious offence.

- Serious offences are those for which the punishment is imprisonment between 3 to 7 years.

- The Act prescribes the procedure for the adoption of children by prospective adoptive parents from India and abroad.

- The Act provides that instead of the court, the District Magistrate (including the Additional District Magistrate) will issue adoption orders.

- Any person unsatisfied with an adoption order passed by the District Magistrate may file an appeal before the Divisional Commissioner, within 30 days from the date of passage of such order.

- Such appeals should be disposed of within 4 weeks from the date of filing of the appeal.

- Additional functions of the District Magistrate: These include:

- Supervising the District Child Protection Unit.

- Conducting a quarterly review of the functioning of the Child Welfare Committee.

- The Act provides that states constitute one or more CWCs for each district for dealing with children in need of care and protection.

Copyright infringement not intended

Related news

- Recently a report on “Review of Guardianship and Adoption Laws” was tabled by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances and Law and Justice in Parliament of India.

- The report found that there are only 2,430 children available for adoption in a country with millions of orphans.

- They mentioned that it is important to get a real picture of the number of orphaned/abandoned children through a district-level survey and the data needs to be updated regularly.

- The panel has suggested that a monthly meeting chaired by the District Magistrate should be held in every district to “ensure that orphan and abandoned children found begging in streets are produced before the Child Welfare Committee and are made available for adoption at the earliest.”

Other Key Recommendations of Parliamentary panel on Review of Guardianship and Adoption Laws

- Granting equal rights to mothers as guardians under the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (HMGA), 1956 instead of treating them as associates to their husbands.

- Joint custody of children during marital disputes or divorce.

- Courts should grant joint custody to both parents when such a decision is necessary for the welfare of the child, or award sole custody to one parent with visitation rights to the other.

- Allowing the LGBTQI (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex) community to adopt children.

- Amend the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 (HMGA) and provide equal treatment to both mother and father as natural guardians as the present law violated the right to equality and right against discrimination envisaged under Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution.

- Need for a new legislation that harmonises the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 and the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (HAMA), 1956 and such a law should cover the LGBTQI community as well.

The present law on guardianship and adoption

- In the case of guardianship of a minor child, Indian laws accord superiority to the father

- Under the religious law of Hindus, or the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, (HMGA) 1956, the natural guardian of a Hindu minor is the father, and after him, the mother.

- The HAMA which applies to Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists allows men and women to adopt if they are of sound mind and are not minors.

- The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 says that the Shariat or the religious law will apply in case of guardianship.

- According to the law, the father is the natural guardian, but custody vests with the mother until the son reaches the age of 7 years and the daughter reaches puberty.

- The Muslim law states that the welfare of the child is supreme to all. This is the reason why Muslim law gives preference to the mother over the father in matters of custody of children in their emotive years.

- In 1999, in the Githa Hariharan vs Reserve Bank of India case, which challenged the HMGA for violating the equality of sexes under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution?

- The Supreme Court held that the term “after” should not be taken as “after the lifetime of the father “, but rather “in the absence of the father”.

- The judgment failed to acknowledge both parents as equal guardians, subordinating a mother’s role to that of the father.

- The Adoption Regulations, 2017 is quiet on adoption by LGBTQI people and neither bans nor allows them to adopt a child.

- It set the eligibility criteria for adoptive parents saying that they should be physically, mentally and emotionally stable, financially capable and should not have any life-threatening medical condition.

- Single men can only adopt a boy while a woman can adopt a child of any gender.

- A child can be given for adoption to a couple only if they have been in a marital relationship for at least 2 years.

- Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) is a statutory body under the Ministry of Women and Child Development.

- It was set up in 1990.

- It became a statutory body under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

- It is the nodal body for the adoption of Indian children and is mandated to monitor and regulate in-country and inter-country adoptions.

https://epaper.thehindu.com/Home/ShareArticle?OrgId=GGDA8SOL2.1&imageview=0&utm_source=epaper&utm_medium=sharearticle

https://t.me/+hJqMV1O0se03Njk9