Description

Copyright infringement not intended

About

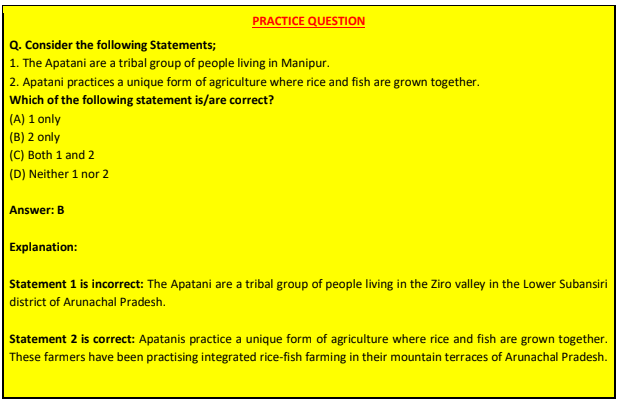

- The Apatani tribe is one of the major ethnic groups of the eastern Himalayas, Arunachal Pradesh.

- They have systematic land use practices and rich traditional ecological knowledge of natural resources management and conservation.

- They practice a unique form of agriculture where rice and fish are grown together. These farmers have been practising integrated rice-fish farming in their mountain terraces of Arunachal Pradesh.

- Apatanis principally use three rice varieties: Emeo, Pyape and Mypia.

- The major festivals of Apatanis are the Myoko, Dree, Yapung and Murung.

- People here believe that these traditional festivals ensure better productivity and well-being.

- The tribe is known for their colourful culture with various festivals, intricate handloom designs, skills in cane and bamboo crafts, and vibrant traditional village councils called bulyañ.

- ‘Bulyañ’ supervises guides and has legal oversight over the activities of individuals that affect the community as a whole.

- They work by addressing the conscience of the people rather than by instilling fear of the law, and by promoting the prevention of unlawful activities rather than by punitive actions.

- Preservation of such an effective socio-legal system is of special value when the formal justice systems of modern times have often come up for criticism.

- The Apatanis are among the few tribes in the world who continue to worship nature. It is their relation with nature that regulates their cultural practices. All the traditional festivals are, in a way, celebrations of nature.

- Conservation of Forest, availability of irrigation water, making wet rice cultivation possible due to strict customs laws governing the utilization of forest resources and hunting practices.

- The Apatanis are known for their judicious utilization of limited land area that evolved out of century-old experimentation. There are separate areas for human settlement, wet rice cultivation, dry cultivation, community burial grounds, pine and bamboo gardens, private plantations and community forests.

- It is an example of a highly successful human adaptation mechanism to the rigour and constraints of upland regions and sustainable management of natural resources.

.jpeg)

Integrated rice-fish cultivation

- Their integrated rice-fish cultivation is a low-input and eco-friendly practice.

- The fish almost depend on the natural food sources of the rice fields and thus, farmers hardly need to use any supplementary fish feeds.

- The farmers sometimes use household and agricultural wastes and excreta of domestic animals like pigs, cows, Mithun and goats to make farming more sustainable and organic.

- Azolla and Lemna are also grown in the field water as nitrogen fixers.

- The organic food grown in the field plays an essential role in feeding fish.

- The water sources in these high-altitude rice fields are mountain streams and rainwater dripped down during the monsoon season.

- Bamboo pipes are being used to distribute water from the networks of earthen irrigation channels.

- Men and women perform different farm duties while preparing the fields for cultivating rice. And during the culture of fish, women folk participate as the major workforce.

- Ancient and old-fashioned agricultural technologies are utilised for cultivation.

- Modern tools like tractors and power tillers are not affordable as well as inaccessible to the farmers.

- Fish improves rice productivity (by 10-15%) by controlling the growth of algae, weeds and insects, providing nutrient input through fish excreta and promoting tillering of the rice through the movement of fish inside the field.

- The zooplankton and algal life forms serve as natural food sources for the fish in the flooded rice fields to enhance aquatic productivity.

- This eco-friendly and economically beneficial practice has made the system unique in terms of aquatic resource utilisation.

- This ecosystem service, in turn, indirectly maintains healthy human-made swamps with better livelihood options for tribal framers.

- The tribe has made a good example of a living cultural landscape where man and environment have harmoniously existed together in a state of interdependence even through changing times, such co-existence being nurtured by the traditional customs and spiritual belief systems.

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/towards-sustainability-arunachal-s-apatanis-use-a-unique-integrated-cultivation-method-it-needs-encouragement-87688