Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- A recent working paper from the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) assessed the criticality levels of 43 select minerals for India.

- Post assessment CSEP extended the earlier minerals assessment for 23 minerals as critical minerals for India.

What are critical minerals?

- Mineral commodities that have important uses and no viable substitutes, yet face potential disruption in supply, are defined as critical to the Nation’s economic and national security.

- Critical minerals are the building blocks of essential modern-day technologies.

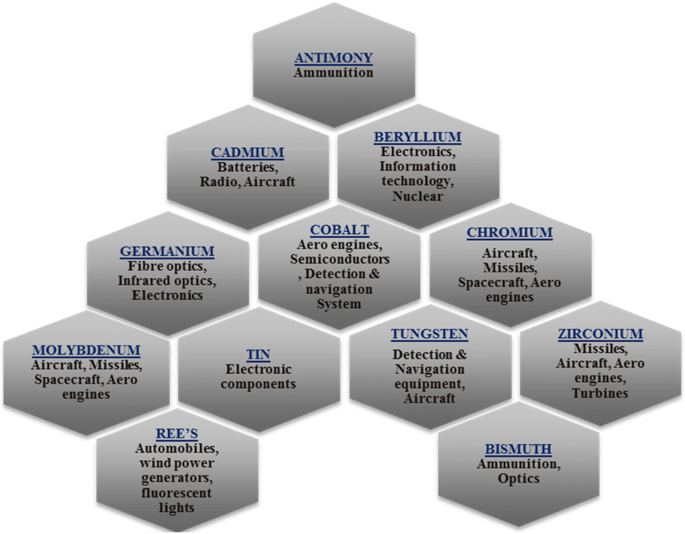

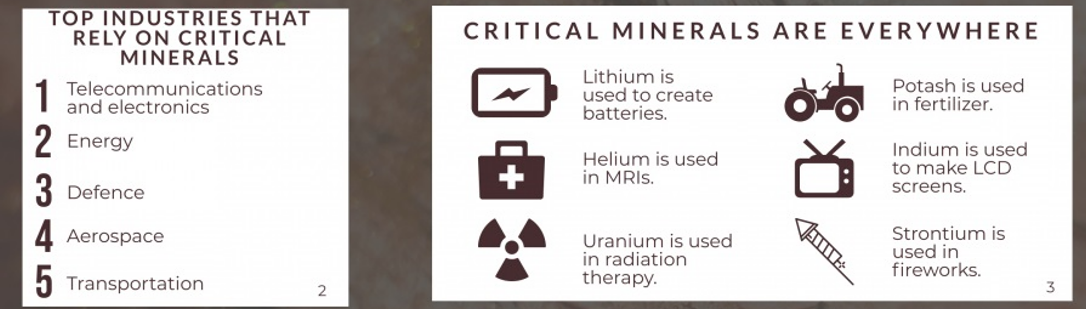

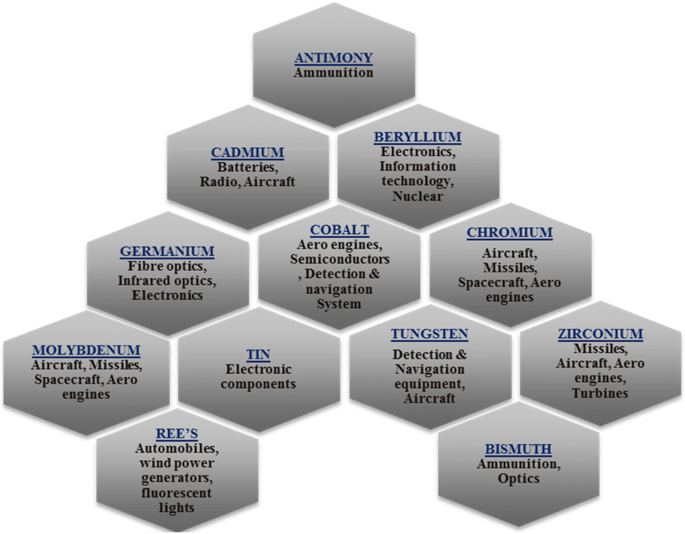

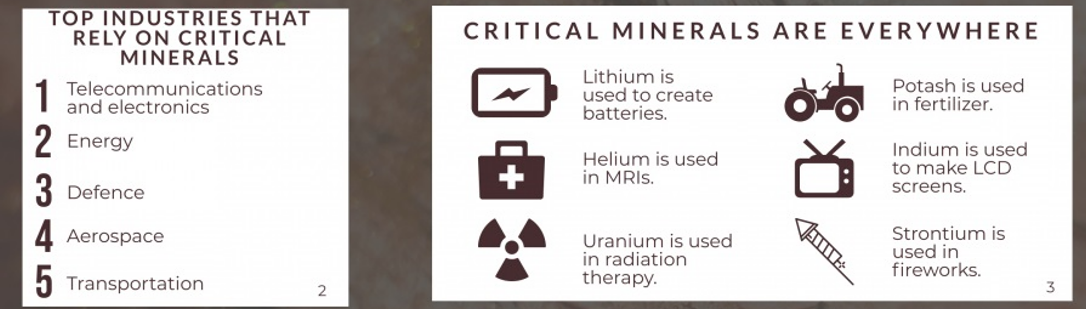

Uses of Critical Minerals

- While some such materials provide inputs to traditional industries, many are crucial for high-tech products required for clean energy, national defence, information technology, aviation and space research.

- These minerals are now used everywhere from –

- Making mobile phones,

- Computers to batteries,

- Electric vehicles and

- Green technologies like solar panels and wind turbines.

- Energy storage systems (ESS) for renewable energy and data transmission hardware.

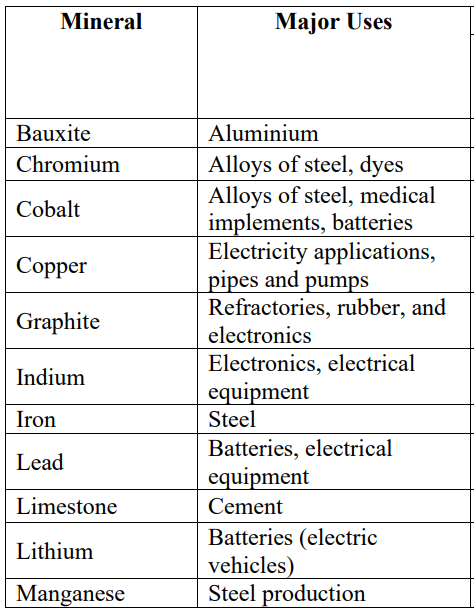

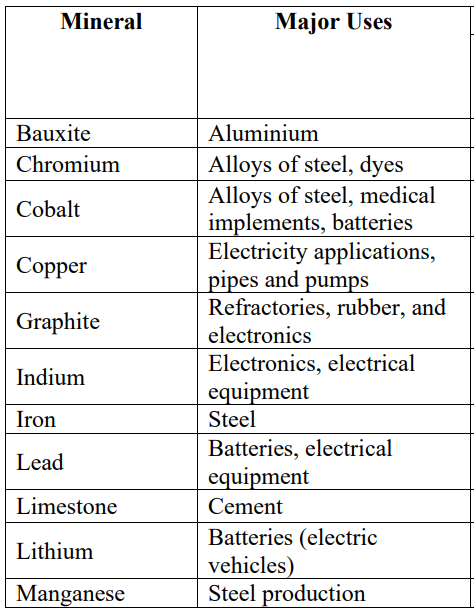

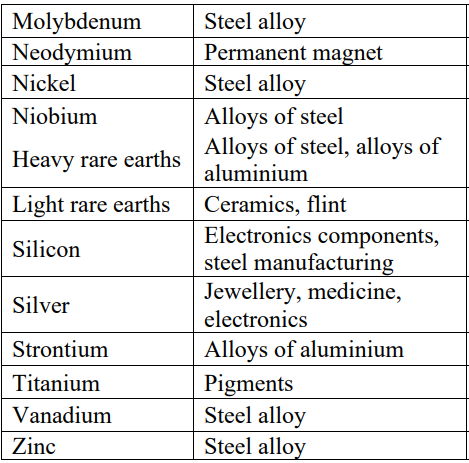

Some major uses include:

- Electric vehicles: cobalt, lanthanum, lithium

- Fuel cells: platinum, palladium, rhodium

- Wind energy technologies: neodymium, dysprosium, terbium

- Aviation sector: titanium

- Photovoltaic solar technologies: cadmium, indium, gallium

How are the Critical Minerals Categorised?

Critical minerals have been classified into three categories based on their end-use industries:

- Traditional — titanium, vanadium

- Sunrise — lithium

- Mixed use — cobalt, nickel, graphite, light rare earth elements (LREEs), heavy rare earth elements (HREEs)

However, there are eight minerals considered to be of greatest interest and these include lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, LREEs, HREEs, titanium and vanadium.

What explains the rising demand for Critical Minerals?

- CRMs are irreplaceable in solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and energy-efficient lighting and are therefore very relevant for fighting climate change and for improving the environment.

- As the world’s clean energy transitions gather pace, demand for critical minerals is expected to grow quickly.

- According to the International Energy Association (IEA), the rise of low-carbon power generation is projected to triple mineral demand from this sector by 2040.

- A US government statement noted that as the world transitions to a clean energy economy, global demand for these critical minerals is set to rapidly increase by 400 per cent to 600 per cent over the next several decades, and, for minerals such as lithium and graphite used in EV batteries, demand will increase by as much as 4,000 per cent.

Why the supply risk?

- The supply-side risks for a mineral are based on the domestic endowment, geopolitical risks of the trade, substitutability and recycling potential.

- Supply risks can be manifested at any of the four stages in the value chain of minerals:

-

- Extraction (exploration and mining),

- Conversion (processing of ore into usable form),

- Transfer (infrastructure, trade, and geopolitical restrictions), and

- Consumption (efficient use in the manufacturing of products).

- Thus, a country with limited supplies of such minerals and with ambitious plans for manufacturing has to think strategically about the overall availability of these minerals.

- Sudden supply shocks or constrictions in the supply chain make a mineral critical, especially if there are no substitutes available in specific applications. This impact is larger if these products contribute to significant value addition in the economy.

- The global concentration of extraction and processing activities, governance regimes and environmental footprints in resource-abundant countries adversely impact availability risks.

- The supply risks of critical minerals may occur due to domestic factors and interruptions in international trade.

- Domestic factors include unrest and civil wars, environmental factors, mining disasters and political conflicts within the producing countries. Risks also arise from trade wars.

.jpeg)

Is there any instance of supply shortfall of Critical Minerals?

- In 2010, China suspended exports of REEs to Japan for 59 days over a territorial dispute.

- The impact was such that the prices of rare earth oxides increased in the range of 60 per cent to 350 per cent and returned to the pre-dispute levels after a year.

- In the case of nickel, there has been a track record of delays and cost overruns in new mines.

- Indonesia, the largest producer of nickel, has banned its exports.

- Similarly, tightening of labour and environment standards in Congo might impact cobalt production and downstream supply chains.

Country-wise List of Critical Minerals

- Based on their individual needs and strategic considerations, different countries create their own lists.

Example: The case of U.S.

- The critical minerals list is revised every three years by the US Geological Survey. The most recent final list is that of 2022.

- These minerals are deemed critical minerals by the US government in light of their role in national security or economic development.

- There must be a clear supply chain strategy as they are mostly imported and are, under the US definition, prone to supply chain disruption.

- Under the 2022 list, there are 50 minerals that are deemed critical:

- Aluminium*

- Antimony

- Arsenic

- Barite

- Beryllium

- Bismuth

- Cerium*

- Cesium

- Chromium

- Cobalt

- Dysprosium

- Erbium

- Europium

- Fluorspar

- Gadolinium*

- Gallium

- Germanium

- Graphite*

- Hafnium

- Holmium

- Indium

- Iridium

- Lanthanum*

- Lithium

- Lutetium

- Magnesium

- Manganese

- Neodymium*

- Nickel

- Niobium

- Palladium*

- Platinum*

- Praseodymium*

- Rhodium*

- Rubidium

- Ruthenium*

- Samarium*

- Scandium

- Tantalum

- Tellurium

- Terbium

- Thulium

- Tin

- Titanium

- Tungsten

- Vanadium

- Ytterbium

- Yttrium

- Zinc

- Zirconium

Critical Minerals of India

CSP Assessment

- As mentioned earlier, in the recent assessment CSEP extended the earlier minerals assessment for 23 minerals as critical minerals for India.

- The assessment was based on their

- Economic importance (demand-side factors) and

- Supply risks (supply-side factors) which are determined through the evaluation of specific indicators.

- Minerals such as antimony, cobalt, gallium, graphite, lithium, nickel, niobium, and strontium are among the 23 assessed to be critical for India.

Many of these are required to meet the manufacturing needs of green technologies, high-tech equipment, aviation, and national defence.

Assessment by Department of Science and Technology (DST)

- India’s Department of Science and Technology (DST), in collaboration with the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), drafted the Critical Minerals Strategy for India in 2016, with a focus on India’s resource requirements till 2030.

- The Indian Critical Minerals Strategy has identified 49 minerals that will be vital for India’s future economic growth. These 49 minerals have been categorised into four categories, depending on their economic importance and supply risk.

Challenges pertaining to Critical Minerals Sector

The China ‘Threat’

- China is typically not considered as a major resource exporter and yet is world’s largest producer of 18 critical minerals.

- The IEA in its report in 2020 has identified that China produces 63 per cent of world’s output of REEs and 45 per cent of molybdenum.

- More than 70 percent of cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with China having a majority ownership of these mines.

- Australia produces 55 percent of world’s lithium with China as its major importer.

- China’s share of refining is around 35 percent for nickel, 50-70 percent for lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90 percent for rare earth elements. China thus plays a crucial role in the global supply chains of critical minerals.

No Domestic availability of Critical Minerals in India

- India has a significant mineral geological potential, many minerals are not readily available domestically.

Reservation of minerals only for public sector undertakings

- Many critical and strategic minerals constitute part of the list of atomic minerals in the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) (MMDR) Act, 1957.

- However, the present policy regime reserves the extraction of these minerals only for Public Sector Undertakings.

Skewed Distribution

- While the demand for critical minerals is set to increase because of the global preference and emphasis on renewable energy, the global supply chain of the critical minerals is highly concentrated and unevenly distributed,

Dependency of China

- China, the most dominant player in the critical mineral supply chains, still struggles with Covid-19-related lockdowns.

- As a result, the extraction, processing and exports of critical minerals are at risk of slowdown.

Supply chain disruption due to Russia-Ukraine War

- Russia is one of the significant producers of nickel, palladium, titanium sponge metal, and the rare earth element scandium.

- Ukraine is one of the major producers of titanium. It also has reserves of lithium, cobalt, graphite, and rare earth elements, including tantalum, niobium, and beryllium.

- The war between the two countries has implications for these critical mineral supply chains.

A Shift in Balance of Power: Impacts the Developing countries

- As the balance of power shifts across continents and countries, the critical mineral supply chains may get affected due to the strategic partnership between China and Russia.

- As a result, developed countries have jointly drawn up partnership strategies, including the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) and G7’s Sustainable Critical Minerals Alliance, while developing countries have missed out.

Lack of mineral reserves

- Manufacturing renewable energy technologies would require increasing quantities of minerals, including copper, manganese, zinc, and indium.

- Likewise, the transition to electric vehicles would require increasing amounts of minerals, including copper, lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

- However, India does not have many of these mineral reserves, or its requirements may be higher than the availability, necessitating reliance on foreign partners to meet domestic needs.

Way Ahead

National Strategy

- India needs to develop a national strategy to ensure resilient critical minerals supply chains, which focuses on minerals found to be critical in this study.

Creation of New List

- Given the increasing importance of critical and strategic minerals, there is an imperative need to create a new list of such minerals in the MMDR Act.

- The list may include minerals such as rhenium, tungsten, cadmium, indium, gallium, graphite, vanadium, tellurium, selenium, nickel, cobalt, tin, the platinum group of elements, and fertilizer minerals such as glauconitic, potash, and phosphate (without uranium).

- These minerals must be prospected, explored, and mined on priority, as any delays may hinder India’s emissions reduction and climate change mitigation timeline.

Special emphasis on Deep Seated Minerals

- The reconnaissance and exploration of minerals must be encouraged, with particular attention given to deep-seated minerals. This will call for a collective effort by the government, ‘junior’ miners, and major mining companies.

Incentivize private explorers

- An innovative regime must be devised to allocate critical mineral mining assets, which adequately incentivizes private explorers, including ‘junior’ explorers.

Clear-cut strategy for processing and assembly of minerals

- India needs to determine where and how the processing of minerals and assembly of critical minerals-embedded equipment will occur.

- Currently, India relies on global supplies of various processed critical minerals, as there are limited domestic sources.

Critical minerals Strategy

- India requires a Critical Minerals Strategy comprising measures aimed at making the country AatmaNirbhar (self-reliant) in critical minerals needed for sustainable economic growth and green technologies for climate action, national defence, and affirmative action for protecting the interests of the affected communities and regions.

Bilateral and Plurilateral Arrangements

- India must actively engage in bilateral and plurilateral arrangements for building assured and resilient critical mineral supply chains.

- Australia, for instance, has the potential to be one of the top suppliers of cobalt and zircon to India, being in the top 3 for global production of these minerals.

- The recently signed Australia-India Critical Minerals Investment Partnership will support further Indian investment in Australian critical minerals projects.

- Australia has a range of development-ready critical minerals projects that, if quickly scaled up, could support the ‘Make in India’ manufacturing plans.

- Critical minerals are already developing as a new base for multilateral collaboration, as seen in the “Quad critical and Emerging Technology Working group”, which aims to develop supply resilience among Quad members -- India, the US, Japan and Australia.

Regular assessment of Critical Minerals

- The assessment of critical minerals for India needs to be updated every three years to keep pace with changing domestic and global scenarios.

Time-bound Action Plan

- A policy framework and time-bound action plan for exploration, processing, use, and recycling of critical minerals in the country - an essential step towards self-sufficiency across several sectors and energy transition.

Reform in Mining and Downstream Sector

- Reforms in mining and downstream sectors of critical minerals can boost not only domestic high-tech manufacturing.

Reducing Import Risks

- The import risks of critical minerals may be reduced by developing resilient supply chains, signing trade agreements, and acquiring mining assets abroad.

Closing Remarks

- Critical minerals are the possible next “Geopolitical Battleground” just as crude oil has been over the last 50 years.

- The Economic Survey 2022-23 has rightly prescribed a “carefully crafted multi-dimensional mineral policy”.

- The skewed distribution of the resource poses a supply risk in the face of its enhanced demand.

- A National Critical Minerals Strategy for India, underpinned by the minerals identified, can help focus on priority concerns in supply risks, domestic policy regimes, and sustainability.

READ:

CRITICAL MINERALS INVESTMENT PARTNERSHIP: https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/critical-minerals-investment-partnership

RARE EARTH ELEMENTS: https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/rare-earth-elements

|

PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. Critical minerals are the possible next “Geopolitical Battleground” just as crude oil has been over the last 50 years. However, the skewed distribution of the resource poses a supply risk in the face of its enhanced demand. What explains the rising demand for Critical Minerals? What are the challenges pertaining to Critical Minerals Sector? What should be India’s Critical Minerals strategy in the coming times? Discuss.

|

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-economics/experts-explain-challenges-india-faces-in-critical-minerals-supply-chains-8566220/