Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- The Union Coal Ministry has sought to rush through the forest diversion process for proposed opencast coal mining in Angul district of Odisha.

- This would require the felling of more than one lakh standing trees in a reserve forest and cause significant disturbance to the elephant herds.

Economic Growth and the Environment

- The issue of economic growth and the environment essentially concerns the kinds of pressures that economic growth, at the national and international level, places on the environment over time.

- The relationship between ecology and the economy has become increasingly significant as humans gradually understand the impact that economic decisions have on the sustainability and quality of the planet.

Economic growth

- Economic growth is commonly defined as increases in total output from new resources or better use of existing resources; it is measured by increased real incomes per capita.

- All economic growth involves transforming the natural world, and it can effect environmental quality in one of three ways. Environmental quality can increase with growth.

Environment with growth

- Increased incomes, for example, provide the resources for public services such as sanitation and rural electricity.

- With these services widely available, individuals need to worry less about day-to-day survival and can devote more resources to conservation.

- Second, environmental quality can initially worsen but then improve as the growth rate rises.

- In the cases of air pollution , water pollution , and deforestation and encroachment there is little incentive for any individual to invest in maintaining the quality of the environment.

- These problems can only improve when countries deliberately introduce long-range policies to ensure that additional resources are devoted to dealing with them.

- Third, environmental quality can decrease when the rate of growth increases.

- In the cases of emissions generated by the disposal of municipal solid waste , for example, abatement is relatively expensive and the costs associated with the emissions and wastes are not perceived as high because they are often borne by someone else.

Future estimates

- The World Bank estimated that, under present productivity trends and given projected population increases, the output of developing countries would be about five times higher by the year 2030 than it is today.

- The output of industrial countries would rise more slowly, but it would still triple over the same period.

- If environmental pollution were to rise at the same pace, severe environmental hardships would occur.

- Tens of millions of people would become sick or die from environmental causes, and the planet would be significantly and irreparably harmed.

- Yet economic growth and sound environmental management are not incompatible. Economic growth will be undermined without adequate environmental safeguards, and environmental protection will fail without economic growth.

Limited Resources

- The earth's natural resources place limits on economic growth. These limits vary with the extent of resource substitution, technical progress, and structural changes.

- For example, in the late 1960s many feared that the world's supply of useful metals would run out. Yet, today, there is a glut of useful metals and prices have fallen dramatically.

- The demand for other natural resources such as water, however, often exceeds supply.

- In arid regions such as the Middle East and in non-arid regions such as northern China, aquifers have been depleted and rivers so extensively drained that not only irrigation and agriculture are threatened but the local ecosystems.

- Some resources such as water, forests, and clean air are under attack, while others such as metals, minerals, and energy are not threatened.

- This is because the scarcity of metals and similar resources is reflected in market prices. Here, the forces of resource substitution, technical progress, and structural change have a strong influence.

- But resources such as water are characterized by open access, and there are therefore no incentives to conserve.

- Effective policies designed to sustain the environment are most necessary because society must be made to take account of the value of natural resources and governments must create incentives to protect the environment.

- Economic and political institutions have failed to provide these necessary incentives for four separate yet interrelated reasons:

1) short time horizons;

2) failures in property rights;

3) concentration of economic and political power; and

4) immeasurability and institutional uncertainty.

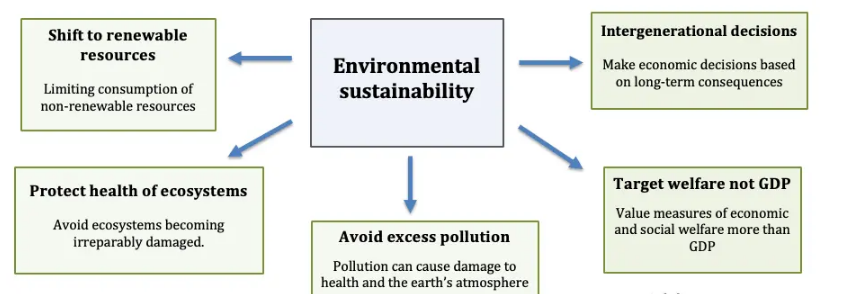

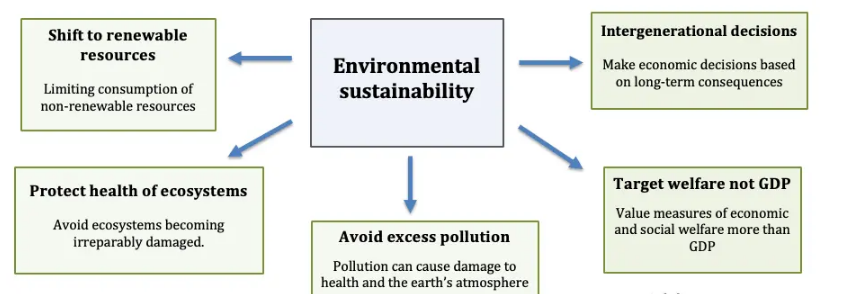

Sustainability

- Although economists and environmentalists disagree on the definition of sustainability, the essence of the idea is that current decisions should not impair the prospects for maintaining or improving future living standards.

- The economic systems of the world should be managed so that societies live off the dividends of the natural resources, always maintaining and improving the asset base.

- Promoting growth, alleviating poverty, and protecting the environment may be mutually supportive objectives in the long run, but they are not always compatible in the short run.

- Poverty is a major cause of environmental degradation , and economic growth is thus necessary to improve the environment. Yet, ill-managed economic growth can also destroy the environment and further jeopardize the lives of the poor.

- In many poor but still forested countries, timber is a good short-run source of foreign exchange.

- When demand for Indonesia's traditional commodity export—petroleum—fell and its foreign exchange income slowed, Indonesia began depleting its hardwood forests at non-sustainable rates in order to earn export income.

- In developed countries, it is competition that can shorten time horizons.

- Competitive forces in agricultural markets, for example, induce farmers to take short-term perspectives for financial survival.

- Farmers must maintain cash flow to satisfy bankers and make a sufficient return on their land investment.

- They therefore adopt high-yield crops, monoculture farming, increased fertilizer and pesticide use, salinizing irrigation methods, and more intensive tillage practices which cause erosion .

Little incentive to reduce damage to the global environment

- "The Tragedy of the Commons" is the classic example of property rights failure. When access to a grazing area, or commons is unlimited, each herdsman knows that grass not eaten today will not be there tomorrow.

- As a rational economic being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain and adds more animals to his herd.

- No herdsman has an incentive to prevent his livestock from grazing the area. Degradation follows and the loss of a common resource. In a society without clearly defined property rights, those who pursue their own interests ruin the public good.

- The cheapest methods of avoiding loss of mineral revenues has been to hurry the development of oil and gas in areas which might revert to open water, thereby, hastening erosion and saltwater intrusion, or putting up levies around the property to maintain it as private property, thus interfering with normal estuarine processes.

- Global or transnational problems such as ozone layer depletion or acid rain produce a similar problem.

- Countries have little incentive to reduce damage to the global environment unilaterally when doing so will not reduce the damaging behavior of others or when reduced fossil fuel use would leave that country at a competitive disadvantage.

- International agreements are thus needed to impose order on the world's nations that would be analogous to property rights.

Concentration of wealth

- Concentration of wealth of wealth within the industrialized countries allows for the exploitation and destruction of ecosystems in less developed countries (LDC) through, for example, timber harvests and mineral extraction.

- The concentration of wealth inside a less developed country skews public policy toward benefiting the wealthy and politically powerful, often at the expense of the ecosystem on which the poor depend.

- Local sustainability is dependent upon the goals of those who have power—goals which may or may not be in line with a healthy, sustainable ecosystem. Furthermore, when an exploiting party has substitute ecosystems available, it can exploit one and then move to the next.

- Japanese lumber firms harvest one country and then move on to another. Here the benefits of sustainability are low and exploiters have shorter time horizons than local interests. This is also an example of how the high discount rates in developed countries are imposed on the management of developing countries' assets.

Environmental policy-making

- Policy-makers and institutions are often unable to grasp the direct and indirect effects of policies on ecological sustainability, nor do they know how their actions will affect other areas not under their control.

- Many contemporary economists and environmentalists argue that the value of the environment should nonetheless be factored into the economic policy decision-making process.

- The goal is not necessarily to put monetary values on environmental resources ; it is rather to determine how much environmental quality is being given up in the name of economic growth, and how much growth is being given up in the name of the environment.

- A danger always exists that too much income growth may be given up in the future because of a failure to clarify and minimize tradeoffs and to take advantage of policies that are good for both economic growth and the environment.

Economic development is often put ahead of environmental sustainability as it involves people’s standards of living. However, quality of life can decline if people live in an economic place with a poor environmental quality because of economic development.

|

Mumbai, India – mini case study

Mumbai is a city that has grown rapidly in both population and economically (full case study notes on Mumbai’s urbanisation here!), but is among the most polluted cities in the world. According to the WHO, Breathing Mumbai’s air is the equivalent of smoking two-and-one-half packs of cigarettes per day. The major sources are road traffic (60% of air pollution) and industry, but domestic sources make a small contribution.

Impacts of economic and urban growth on Mumbai’s environment

1. Nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide pollution worsened in the last part of the 20th century

2. Particulate matter levels got worse too

3. Atmospheric sulphur dioxide and lead declined, because of the reduced use of high sulphur fuel, especially by some major industries, and reduced lead in petrol.

4. The maximum permissible levels of lead are sometimes exceeded because many vehicles run on leaded petrol.

5. World Health Organisation limits for particulate pollution were exceeded in all areas and during all seasons in 1998. 97% of Mumbai’s population live in high pollution zones.

6. The south-eastern corner of the Northern Suburbs is also affected by the burning of refuse at the 100 ha municipal garbage dump.

7. It has been estimated that 20m work days are lost or affected because of 24,000 cases of chronic bronchitis, 900,000 cases of asthma, and other pollution-related illnesses.

8. Water pollution from untreated sewage and industrial waste is prevalent, and water-borne diseases are common.

9. Improvements have been made in recent years, for example by the construction of two marine outfalls, the provision of many more standpipes and the treatment of all piped water, but water-related diseases have not declined significantly.

10. 75% of all sewage is discharged untreated into local waterways and coastal waters, and the water supply is beset by problems of low pressure and supply interruptions, allowing contamination before use.

|

- Economic growth means an increase in real output (real GDP). Therefore, with increased output and consumption we are likely to see costs imposed on the environment. The environmental impact of economic growth includes the increased consumption of non-renewable resources, higher levels of pollution, global warming and the potential loss of environmental habitats.

- However, not all forms of economic growth cause damage to the environment. With rising real incomes, individuals have a greater ability to devote resources to protecting the environment and mitigate the harmful effects of pollution. Also, economic growth caused by improved technology can enable higher output with less pollution.

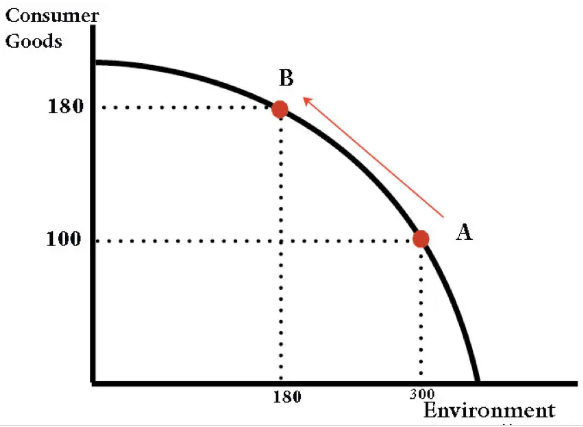

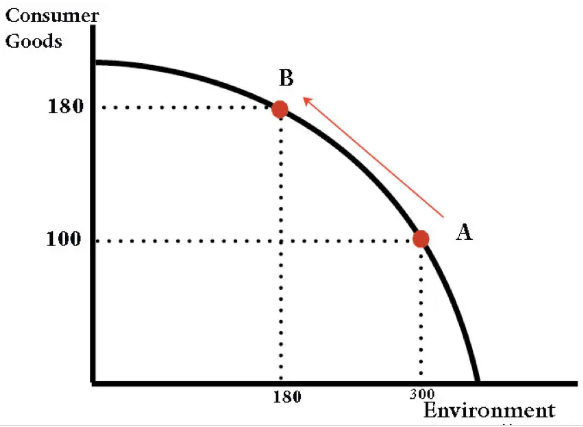

Classic trade-off between economic growth and environmental resources

This PPF curve shows a trade-off between non-renewable resources and consumption. As we increase consumption, the opportunity cost implies a lower stock of non-renewable resources.

For example, the pace of global economic growth in the past century has led to a decline in the availability of natural resources such as forests (cut down for agriculture/demand for wood)

- A decline in sources of oil/coal/gas

- Loss of fishing stocks – due to overfishing

- Loss of species diversity – damage to natural resources has led to species extinction.

External costs of economic growth

Pollution

Increased consumption of fossil fuels can lead to immediate problems such as poor air quality and soot, (London smogs of the 1950s). Some of the worst problems of burning fossil fuels have been mitigated by Clean Air Acts – which limit the burning of coal in city centres. Showing that economic growth can be consistent with reducing a certain type of pollution.

Less visible more diffuse pollution

While smogs were a very clear and obvious danger, the effects of increased CO2 emissions are less immediately obvious and therefore there is less incentive for policymakers to tackle. Scientists state the accumulation of CO2 emissions have contributed to global warming and more volatile weather. All this suggests economic growth is increasing long-term environmental costs – not just for the present moment, but future generations.

Damage to nature

Air/land/water pollution causes health problems and can damage the productivity of land and seas.

Global warming and volatile weather

Global warming leads to rising sea levels, volatile weather patterns and could cause significant economic costs

Soil erosion

Deforestation resulting from economic development damages soil and makes areas more prone to drought.

Loss of biodiversity

Economic growth leads to resource depletion and loss of biodiversity. This could harm future ‘carrying capacity of ecological systems’ for the economy. Though there is uncertainty about the extent of this cost as the benefit of lost genetic maps may never be known.

Long-term toxins

Economic growth creates long-term waste and toxins, which may have unknown consequences. For example, economic growth has led to increased use of plastic, which when disposed of do not degrade. So there is an ever-increasing stock of plastic in the seas and environment – which is both unsightly but also damaging to wildlife.

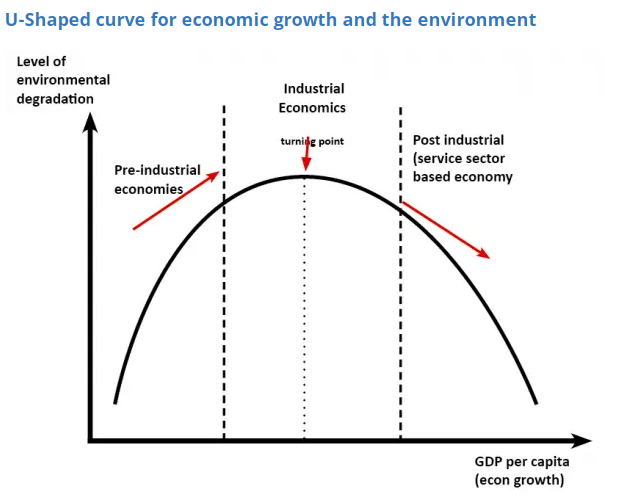

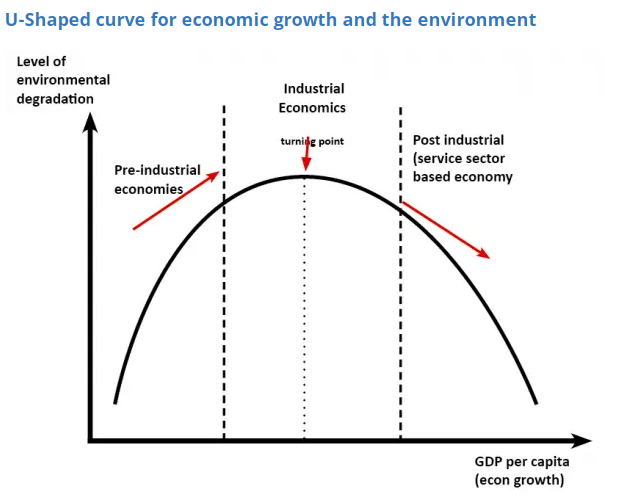

One theory of economic growth and the environment is that up to a certain point economic growth worsens the environment, but after that the move to a post-industrial economy – it leads to a better environment.

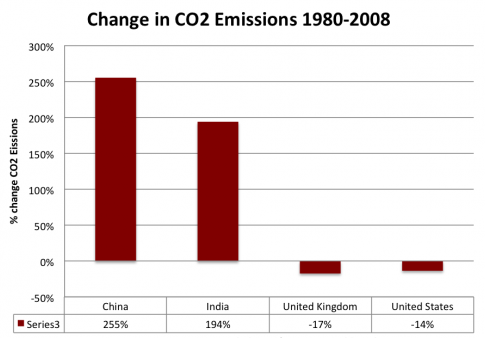

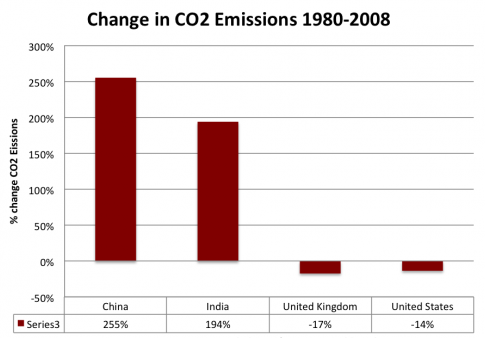

For example – since 1980, the UK and the US have reduced CO2 emission. The global growth in emissions is coming from developing economies.

Another example – In early days of growth, economies tend to burn coal/wood – which cause obvious pollution. But, with higher incomes, an economy can promote cleaner technology which limits this air pollution. However, in a paper “Economic growth and carrying capacity” by Kenneth Arrow et al. they caution about this simplistic u-shape. As the authors state:

“Where the environmental costs of economic activity are home by the poor, by future generation, or by other countries, the incentives to correct the problem are likely to be weak”

- It may be true there is a Kuznets curve for some types of visible pollutants, but it is less true of more diffuse and less visible pollutants. (like CO2)

- The U-shaped maybe true of pollutants, but not the stock of natural resources; economic growth does not reverse the trend to consume and reduce the quantity of non-renewable resources.

- Reducing pollution in one country may lead to the outsourcing of pollution to another, e.g. we import coal from developing economies, effectively exporting our rubbish for recycling and disposal elsewhere.

- Environmental policies tend to deal with pressing issues at hand but ignore future intergenerational problems.

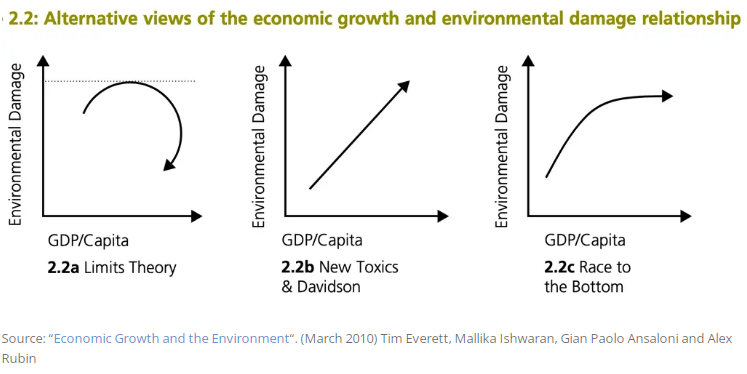

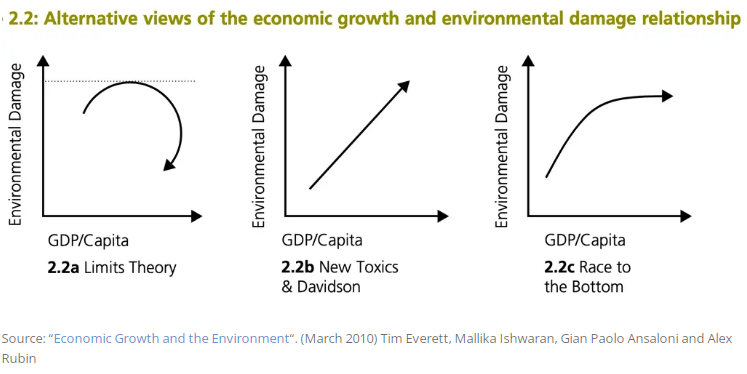

Other models of a link between economic growth and environment

Limits Theory

- This suggests that economic growth will damage the environment, and damage will itself start to act as a brake on growth and will force economies to deal with economic damage.

- In other words, the environment will force us to look after it. For example, if we run down natural resources, their price will rise and this will create an incentive to find alternatives.

New toxics

- This is more pessimistic suggesting that economic growth leads to an ever-increasing range of toxic output and problems, some issues may get solved, but they are outweighed by newer and more pressing problems which are difficult if impossible to overturn.

- This model has no faith that the free-market will solve the problem because there is no ownership of air quality and many of the effects are piling up on future generations; these future effects cannot be dealt with by the current price mechanism.

Race to the bottom

- This suggests that in the early stages of economic growth, there is little concern about the environment and often countries undermined environmental standards to gain a competitive advantage – the incentive to free-ride on others’ efforts. However, as the environment increasingly worsens, it will reluctantly force economies to reduce the worst effects of environmental damage. This will slow down environmental degradation but not reverse past trends.

Economic growth without environmental damage

Some ecologists argue economic growth invariably leads to environmental damage. However, there are economists who rightly argue that economic growth can be consistent with a stable environment and even improvement in the environmental impact. This will involve

A shift from non-renewables to renewables

- A recent report suggests that renewable energy is becoming cheaper than more damaging forms of energy production such as burning coal and in 2018 – this has led to a 39% drop in new construction starts from 2017, and an 84% drop since 2015.

Social cost pricing.

- If economic growth causes external costs, economists state it is socially efficient to include the external cost in the price (e.g. carbon tax).

- If the tax equals the full external cost, it will lead to a socially efficient outcome and create a strong incentive to promote growth that minimises external costs.

Treat the environment as a public good

- Environmental policy which protects the environment, through regulations, government ownership and limits on external costs can, in theory, enable economic growth to be based on protection of the environmental resource.

Technological development

- It is possible to replace cars running on petrol with cars running on electricity from renewable sources. This enables an increase in output, but also a reduction in the environmental impact.

- There are numerous possible technological developments which can enable greater efficiency, lower costs and less environmental damage.

- Include quality of life and environmental indicators in economic statistics.

- Rather than targetting GDP, environmental economists argue we should target a wider range of living standards + living standards + environmental indicators. (e.g. Genuine Progress Indicators GPI)

https://epaper.thehindu.com/Home/ShareArticle?OrgId=GUF9PIM30.1&imageview=0