Description

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: https://www.lawinsider.in/columns/what-is-the-history-of-reservation-in-india

Context: Religion-based reservation in a secular country like India raises constitutional questions.

Religion-based reservations

- Religion-based reservations refer to the policy of providing special benefits, quotas, or reservations in educational institutions and government jobs based on religious affiliation or identity.

- In the Indian context, these reservations aim to address historical socio-economic disparities faced by certain religious communities, particularly those identified as socially and educationally backward.

- The purpose of religion-based reservations is rooted in the principle of social justice and affirmative action to uplift marginalized sections of society.

- Historically, certain religious communities have faced discrimination and exclusion, leading to socio-economic backwardness. Reservation policies seek to remedy these inequalities by providing opportunities for education, employment, and representation in government services.

Pre-Independence Era

- During the 19th and early 20th centuries, India witnessed various social reform movements aimed at addressing caste-based discrimination and social inequities.

- Leaders like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Jyotirao Phule, and B.R. Ambedkar advocated for social reforms and upliftment of marginalized communities, including those based on religious identities.

Movements for Social Reform

- Brahmo Samaj: Founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, this movement aimed at reforming social practices and promoting education and gender equality.

- Satyashodhak Samaj: Initiated by Jyotirao Phule, this movement focused on empowering lower-caste and Dalit communities through education and social upliftment.

- Dalit Movement: Leaders like B.R. Ambedkar emerged as a strong advocate for the rights and upliftment of Dalits (Scheduled Castes), highlighting the need for reservations based on social and educational backwardness.

Discussions on Representation and Social Justice

- Various social and political discussions during this period centred around representation and social justice for marginalized communities, including those defined by religion.

- The need for adequate representation of religious minorities in legislative bodies and government services was highlighted.

Communal Award (1932) and Poona Pact (1932)

- The Communal Award of 1932 proposed separate electorates for different religious communities, including Muslims, Sikhs, and others.

- The Poona Pact signed between B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi in 1932, led to the abandonment of separate electorates in favour of reserved seats for marginalized communities within the general electorate.

- These discussions and agreements laid the groundwork for future reservation policies based on social and educational backwardness rather than religious identity alone.

Post-Independence Era

- India gained independence from British rule in 1947. The Constituent Assembly, comprising elected representatives from various political parties and social groups, was tasked with drafting the Constitution of India.

- The Indian Constitution was enacted on January 26, 1950, marking the beginning of India as a sovereign democratic republic. The Constitution laid down the fundamental principles and governance structure of the nation.

- The first general elections were held in 1951-52, establishing India as the world's largest democracy. During this period, there were extensive debates and discussions on the issue of reservations, particularly in the context of representation for historically marginalized communities.

Constitutional Framework

- The Constitution of India has provisions for affirmative action to ensure social justice and equality of opportunity.

- Articles 15(4) and 16(4) enable the state to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens, including Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), to address historical disadvantages.

- While Article 15 prohibits discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth, it allows for special provisions for the advancement of certain sections of society. The principle of substantive equality is emphasized, which aims at achieving equitable outcomes rather than mere formal equality.

|

Reservation system in India

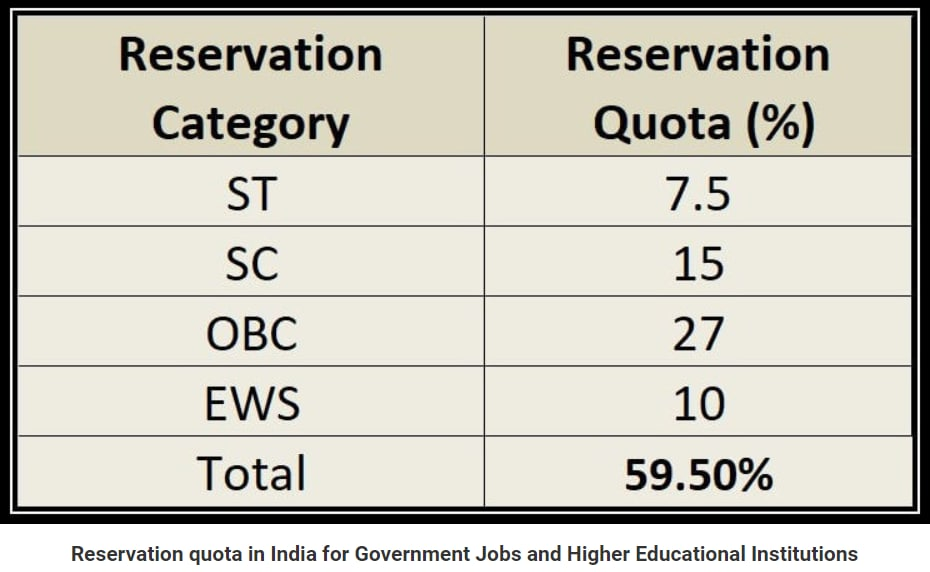

●The reservation system in India is a policy of affirmative action aimed at addressing historical socio-economic disparities and promoting social inclusion in public employment and educational institutions.

●This system primarily benefits the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), economically weaker sections (EWS), and persons with disabilities (PWDs) who have been historically underrepresented in these sectors.

●Scheduled Caste status under Article 341 is currently limited to Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists. Muslims and Christians are excluded from this category, which could be considered a form of religion-based reservation.

|

Religion-based Reservations Emergence

Factors and Influences

- Mandal Commission (1979): One of the key developments during this period was the appointment of the Mandal Commission in 1979. The commission was tasked with identifying socially and educationally backward classes and recommending measures for their advancement, including reservations in educational institutions and government jobs.

- Reservation Demands from Various Religious Communities: During the 1960s to 1980s, there were increasing demands from various religious communities, including Muslims, for reservations based on social and educational backwardness. These demands were influenced by socio-economic disparities faced by certain religious groups.

Landmark Cases and Decisions

- The Supreme Court has emphasized that reservation policies should be based on social and educational backwardness rather than religious identity alone. Courts have upheld the inclusion of certain Muslim communities within the OBC category based on objective criteria and empirical data.

- The courts have emphasized that reservations should not violate the principle of secularism and should be justified by evidence of social and educational backwardness.

|

Key Supreme Court Judgments

|

|

The State of Madras v/s. Smt. Champakam Dorairajan Case1951

|

●This case challenged reservations in educational institutions solely based on caste, arguing that it violated the principle of equality under the Indian Constitution.

●The Supreme Court struck down the caste-based reservations; this judgment highlighted the need to consider broader criteria beyond caste alone for implementing affirmative action measures.

|

|

Indra Sawhney v/s Union of India Case 1992

|

●Introduced the concept of the "creamy layer" exclusion within OBC reservations, excluding affluent sections from benefiting.

●Imposed a 50% cap on total reservations to maintain efficiency and prevent reverse discrimination.

●Stated that reservations in promotions are generally not permissible, except for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

●Defined important limitations and criteria for reservation policies, ensuring fairness and efficiency in their implementation.

|

|

M. Nagaraj v/s Union Of India Case 2006

|

●Addressed the issue of reservations for SCs and STs in promotions in public employment.

●Upheld Article 16(4A), allowing reservations for SCs and STs in promotions, subject to certain conditions.

●Established criteria include social and educational backwardness, inadequate representation, and maintenance of administrative efficiency.

●Provided clarity on the conditions and requirements for extending reservations to promotions within the framework of Article 16.

|

|

Jarnail Singh v/s Lachhmi Narain Gupta Case 2018

|

●Clarified the applicability of the "creamy layer" concept to reservations for SCs and STs in promotions.

●Affirmed that the creamy layer exclusion applies to SCs and STs in promotions to prevent the perpetuation of benefits to affluent sections.

●Emphasized that quantifiable data on backwardness is not mandatory for justifying reservations in promotions for SCs and STs.

●Reinforced the importance of ensuring the effectiveness and fairness of reservation policies, even within the context of promotions.

|

|

Janhit Abhiyan v/s Union of India, 2022

|

●Examined the validity of the 103rd Constitutional Amendment, which introduced 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) among forward castes.

●The Supreme Court upheld the validity of the amendment, allowing for EWS reservations in government jobs and educational institutions.

●Acknowledged the government's efforts to address economic disparities and expand the scope of affirmative action beyond traditional categories of reservation.

|

Reservation Implementation

- The Mandal Commission submitted its report in 1980, recommending reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in government jobs and educational institutions. This report had significant implications for reservation policies in India, including considerations for reservations based on social and educational backwardness across religious communities.

State-Level Initiatives

- Kerala: Religion-based reservation was first introduced in the Travancore-Cochin state in 1936. Communal reservation replaced religion-based reservation in 1952, encompassing Muslims within the OBCs due to their historical socio-economic status. After Kerala's formation in 1956, all Muslims were included in specific sub-quota categories within the OBCs, with a dedicated sub-quota of 10% (now 12%) within the overall OBC reservation quota.

- Karnataka: The Third Backward Classes Commission headed by Justice O Chinnappa Reddy (1990) recognized Muslims as fulfilling the requirements for being considered among backward classes. In 1995, the government implemented a 4% reservation for Muslims within the OBC quota, including 36 Muslim castes from the central list of OBCs.

- Tamil Nadu: Based on the recommendations of the Second Backward Classes Commission headed by J A Ambasankar (1985), Tamil Nadu passed a law in 2007 providing a sub-category of Muslims with 3.5% reservation within the OBC quota.

- Andhra Pradesh: The question of Muslim reservation was referred to the Andhra Pradesh Backward Classes Commission in 1994. By 2004, based on the commission's report highlighting the backwardness of Muslims, the state government provided a 5% reservation. However, this initiative faced legal challenges and was struck down by the High Court due to procedural issues.

- Telangana: The State Government proposed a 12% reservation for OBC Muslims based on reports highlighting educational and economic disparities compared to other communities. The proposal exceeded the Supreme Court-mandated 50% reservation cap and was referred to the central government for inclusion in the Ninth Schedule, but did not progress further.

|

Central-Level Interventions

●Justice Rajinder Sachar Committee (2006): Found that the Muslim community was almost as backward as Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), and more backward than non-Muslim Other Backward Classes (OBCs), highlighting the need for targeted interventions.

●Justice Ranganath Misra Committee (2007): Suggested a 15% reservation for minorities, with 10% specifically for Muslims, recognizing the socio-economic challenges faced by minority communities.

●Executive Order (2012): The government issued an order providing 4.5% reservation for minorities within the existing 27% OBC quota, aiming to address socio-economic disparities among minority communities.

|

Contemporary Issues and Debates

- The reservation system continues to face scrutiny regarding its effectiveness in achieving social justice and equitable representation. Debates centre around the balance between meritocracy and affirmative action, as well as concerns about perpetuating caste-based identities.

- Several legal challenges have emerged against the reservation policies, questioning their constitutionality and impact on governance and public institutions. Political parties often have differing stances on reservation policies, leading to ongoing debates and policy reforms.

Proposed Reforms and Alternatives

- Merit-based Alternatives: Some stakeholders propose shifting towards merit-based criteria while ensuring inclusive policies for socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

- Targeted Welfare Measures: Alongside reservations, there is a growing emphasis on targeted welfare measures aimed at addressing broader socio-economic disparities, including education, healthcare, and employment opportunities.

- Enhanced Data Collection: There are calls for more comprehensive data collection and analysis to identify and address specific challenges faced by different communities, enabling more nuanced policy interventions.

Challenges and Way Forward

- The success of religion-based reservations depends on establishing the social and educational backwardness of specific communities through empirical studies and commission reports.

- Balancing secular principles with the objectives of social justice remains a challenge in formulating reservation policies that address historical inequalities without compromising constitutional values.

- The formulation of reservation policies requires sensitivity to local socio-economic contexts and adherence to constitutional principles, ensuring that the benefits reach the most marginalized and deserving sections of society.

Conclusion

- The issue of religion-based reservations in India is a complex issue that demands careful consideration of constitutional mandates, legal proceedings, empirical evidence, and socio-economic realities. While efforts have been made to address historical injustices through affirmative action, the challenge lies in formulating inclusive policies that uphold both secularism and social justice, ensuring equitable opportunities for all citizens irrespective of religious identity.

Source:

Indian Express

Lawinsider

Wikipedia

|

PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. The Sachar Committee report found that the Muslim community as a whole was almost as backwards as SCs and STs. Based on this, what are the arguments for and against providing a separate reservation quota for the entire Muslim community, instead of the current practice of identifying specific backward groups among Muslims? How can such a move be squared with the secular principles of the Constitution?

|