Copyright infringement not intended

Details:

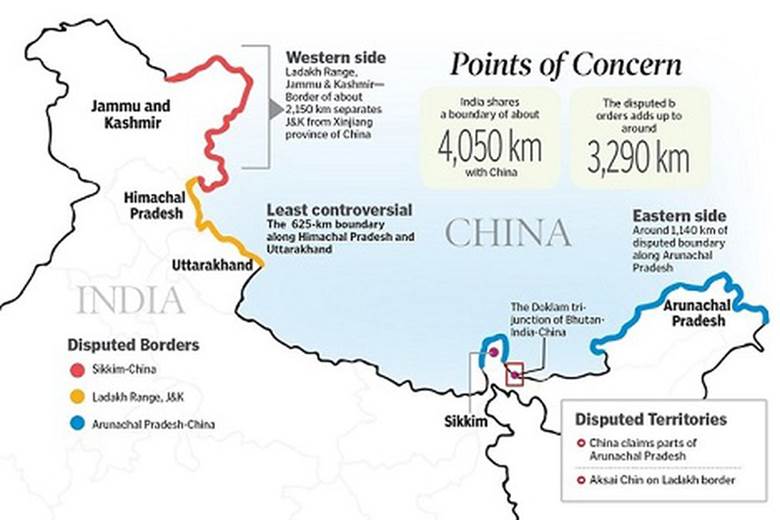

The root cause lies in an ill-defined, 3,440km (2,100-mile)-long border that both countries dispute.Four states - Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand (erstwhile part of UP), Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh and Union Territories of Ladakh (erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir) share a border with China.

The Sino-Indian border is generally divided into three sectors namely: Western sector, Middle sector, and Eastern sector.

Western Sector

In the western sector, India shares about a 2152 km border with China. It is between the union territory of Ladakh (erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir) and the Xinjiang province of China. The territorial dispute in the western sector is over Aksai Chin. India claims it as part of erstwhile Kashmir, while China claims it is part of Xinjiang.

The dispute is said to be due to the failure of the British empire as it failed to demarcate a legal border between both countries. During the British rule in India two borderlines were proposed – Johnson’s line and McDonald line in 1865 and 1893 respectively.

.jpg)

The Johnson’s line shows Aksai Chin in Ladakh i.e. under India’s control whereas McDonald Line places it under China’s control. India considers Johnson Line as a rightful national border with China, while on the other hand, China considers the McDonald Line as the correct border with India. The different claims and perceptions of LAC have led to an overlapping area, within that area lies a small zone which both the sides patrol causing clashes of the Indian and the Chinese army.

At present, Line of Actual Control (LAC) is the line separating Indian areas of Ladakh from Aksai Chin. It is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line.

Middle Sector

In the middle sector, India shares about 625km of the border with China. This is the only sector where the both countries have less disagreement. The border runs from Ladakh to Nepal. The states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand touch the border with Tibet in this sector.

Eastern Sector

In the eastern sector, India shares a 1140km boundary with China. The boundary line is called McMahon Line runs from the eastern limit of Bhutan to a point near the Talu Pass at the trijunction of Tibet, India, and Myanmar. The majority of the territory of Arunachal Pradesh is claimed by China as a part of Southern Tibet.

China considers the McMahon line illegal. McMahon proposed the line in the Simla Accord in 1914 to settle the boundary between Tibet and India, and Tibet and China. Though the Chinese representatives at the meeting initialed the agreement, they subsequently refused to accept it.

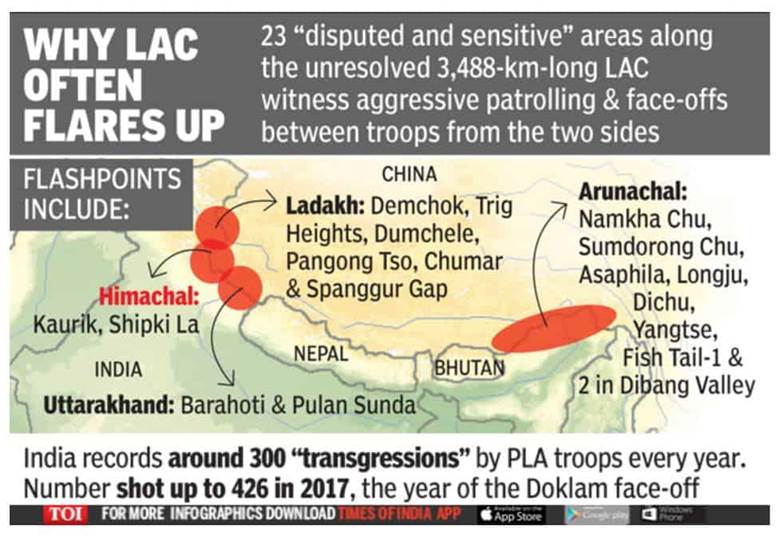

China claims about 90,000 sq km of India’s territory in the northeast, including Arunachal, while India says 38,000 sq km of land in China-occupied Aksai Chin should be a part of Ladakh. There are several disputed areas along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), including in Himachal, Uttarakhand and Sikkim.

In Ladakh, the disputed areas include:

In Himachal Pradesh , the disputed areas are

In Uttarakhand, the disputed areas are-

In Sikkim, the disputed areas include:

Disputed areas in Arunachal Pradesh include:

.jpg)

There are five Border Personnel Meeting points (BPM) for holding rounds of dispute resolution talks among the military personnel. These are – Bum La and Kibithu in Arunachal Pradesh; Daulat Beg Oldi and Chushul in Ladakh, and Nathu La in Sikkim.

Historically, Beijing has made some offers on settling the border dispute. The simplest of them was the “package" deal.

It involved both the countries recognizing the status quo—Chinese occupation of Aksai Chin and Indian sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh—on both fronts. This offer was first made by former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1960. This offer is arguably the best formula for settlement according to historian Mahesh Shankar because the region is not strategically important to India.

The offer was however rejected by former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as he was concerned that any concession, even in the west would only invite further aggression from Beijing all across the frontier.

Note: While Mahesh Shankar’s argument is indeed compelling, it must also be noted that according to Historian Sarvepalli Gopal New Delhi had always recognized the McMahon line in the west which awarded Arunachal Pradesh (then the North-East Frontier Agency) to India. Thus, a straight swap seemed unreasonable.

As Justice A.G. Noorani quoted:

“If a thief breaks into your house and steals your coat and your wallet, you don’t say to him that he can have the coat if he returns the wallet. You expect him to return all that he has stolen from you."

The second offer, which is still better for New Delhi than the “package" deal, is the “LAC plus solution"

The LAC-plus solution involved recognition of the status quo in the east and some concessions by China in the west. This offer, however, was not followed through on the Indian side.

And very soon, in the year 1985, China hardened its stand against this offer and it has roughly remained the same till date.

Beijing has specifically eyed Tawang, and asked India to put forward its offer on the eastern front, following which it would reveal what it could offer on the western front.

Any solution which requires India trading away any part of Arunachal Pradesh will not pass muster in New Delhi.

A resolution of the border dispute seems far away. Economist Arun Shourie summarized it aptly:

We really should not be in a hurry to ‘solve’ the dispute—especially not when the distance between China and India is as vast as it has become;

Secondly, an agreement is worth something only if we are sure that the other side would not violate it. And we can actually make it expensive for the other side if it violates the agreement.

© 2025 iasgyan. All right reserved