Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- India’s jute economy is faltering while Bangladesh’s is flourishing: Experts.

Jute industry of West Bengal

- The jute industry of West Bengal is facing a major crisis and impacting the livelihoods of thousands of workers and farmers.

- The sector directly provides employment to about 70 lakh workers in the country and sustains over 40 lakh farm families.

- With 70 of the 93 (2016 data) mills in India, West Bengal is the hub of India’s jute industry, valued at around Rs 10,000 crore. Several mills are on the verge of closing.

Issue

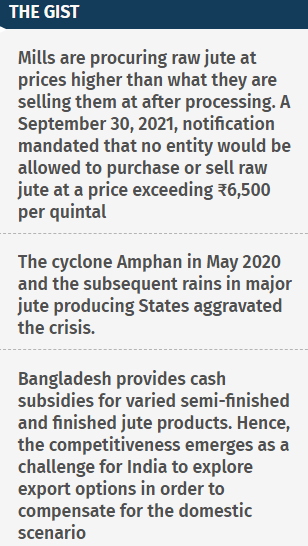

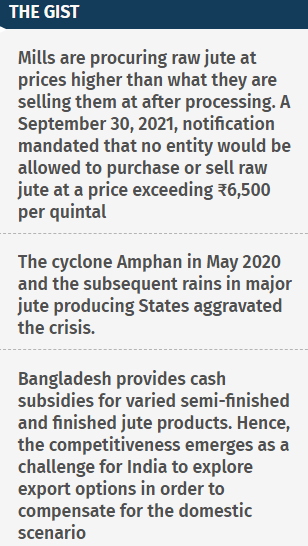

- The issue is the procurement of raw jute at a higher cost but the final output is being sold at higher rates.

- The government procures raw jute from farmers at a fixed Minimum Support Price (MSP) which is Rs 4,750 per quintal for the financial year 2022-23.

- This reaches the mill at Rs. 7,200 per quintal, that is, Rs. 700 more than the Rs. 6,500 per quintal cap for the final product.

- The jute mills do not procure raw material directly from the farmers because the mills are far from farmers and the process of procurement takes time. No single farmer produces enough to meet the entire demand of a mill. Thus, the middlemen or traders procure raw jute from multiple farmers and then trade it to the mills.

Supply Crunch

- The occurrence of Cyclone Amphan in May 2020 and the subsequent rains in major jute producing States aggravated the crisis. These events led to lower acreage, which in turn led to lower production and yield compared to previous years.

- Additionally, as the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) stated in its report, this led to production of a lower quality of jute fibre in 2020-21 as water-logging in large fields resulted in farmers harvesting the crop prematurely.

- Acreage issues were accompanied by hoarding at all levels – right from the farmers to the traders.

Impact

- As the jute sector provides direct employment to 3.70 lakh workers in the country and supports the livelihood of around 40 lakh farm families, closure of the mills is a direct blow to workers and indirectly, to the farmers whose production is used in the mills. West Bengal, Bihar and Assam account for almost 99% of India’s total production.

India’s Jute Industry

- India is the world’s biggest producer of jute, followed by Bangladesh. Jute is primarily grown in West Bengal, Odisha, Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Andhra Pradesh.

- The jute industry in India is 150 years old. There are about 79 jute mills in the country, of which about 60 are in West Bengal along both the banks of river Hooghly.

- Jute production is a labour intensive industry. It employs about two lakh workers in the West Bengal alone and 4 lakh workers across the country.

Jute as a crop and its benefits

- Jute is the only crop where earnings begin to trickle in way before the final harvest. The seeds are planted between April and May and harvested between July and August.

- The leaves can be sold in vegetable markets for nearly two months of the four-month jute crop cycle. The tall, hardy grass shoots up to 2.5 metres and each part of it has several uses.

- The outer layer of the stem produces the fibre that goes into making jute products. But the leaves can be cooked, the inner woody stems can be used to manufacture paper and the roots, which are left in the ground after harvest, improve the yield of subsequent crops.

- Compared to rice, jute requires very little water and fertiliser. It is largely pest-resistant, and its rapid growth spurt ensures that weeds don’t stand a chance.

- To top it all, the monetary returns on jute are twice that of paddy. An acre of land produces approximately nine quintals of fibre.

- Jute brings home higher returns compared to most cash and food crops, and it is also a massive winner on the sustainability front.

- Jute is the second most abundant natural fibre in the world. It has high tensile strength, acoustic and thermal insulation, breathability, low extensibility, ease of blending with both synthetic and natural fibres, and antistatic properties.

- Jute can be used: for insulation (replacing glass wool), geotextiles, activated carbon powder, wall coverings, flooring, garments, rugs, ropes, gunny bags, handicrafts, curtains, carpet backings, paper, sandals, carry bags, and furniture.

- A ‘Golden Fibre Revolution’ has long been called for by various committees, but the jute industry is in dire need of basic reforms.

|

Climatic Requirements

Temperatures ranging to more than 25 °C and relative humidity of 70%–90% are favorable for successful Jute cultivation. Jute requires 160–200 cm of rainfall yearly with extra needed during the sowing period. River basins, alluvial or loamy soils with a pH range between 4.8 and 5.8 are best for jute cultivation.

Constant rain or water-logging is harmful. The new gray alluvial soil of good depth, receiving salt from annual floods, is best for jute. Flow ever jute is grown widely in sandy loams and clay loams.

Retting is a process in which the tied bundles of jute stalks are taken to the tank by which fibres get loosened and separated from the woody stalk. The bundles are steeped in water at least 60 cm to 100 cm depth.

Stripping is the process of removing the fibres from the stalk after the completion of retting.

|

Problems of Jute Industry in India

The major problems of Indian Jute Industries are mentioned below:

- High cost of production: Equipments for production are all worn out, outmoded in design. Many mills are uneconomic. Products are made costlier.

- Storage of raw Jute: Jute industry suffers from inadequate supply of raw jute.

- Shortage of Power Supply: Load-shedding creates problem of under-utilization of capacity.

- Growth of Jute mills in Bangladesh and loss of foreign market: Newly started jute industry in Bangladesh has captured some of the market of Indian jute goods.

- Emergence of substitute goods against gunny bags and loss of demand for jute goods both at home and abroad: Indian jute goods have been losing ground in the world market primarily due to keen competition from synthetic substitutes and also supplies from Bangladesh and China.

- Effects of Partition: Due to Partition in 1947, the erstwhile best quality jute-producing areas went to the then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) while the jute mills were mainly concentrated in the Indian Territory. Bangladesh received 82% of the good quality jute growing tract India retained 95% of the mills. The resultant acute shortage of raw jute forced some of the mills to close down.

- Stiff Competition: Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand and China are recently posing grave threat to India in international export market.

- Low Yield Per Acre: India produces very low quantity of jute per unit of land. In Bangladesh the average yield per hectare is 1.62 tonnes. It is only 1.3 tonnes per hectare in India. The corresponding figure of jute production in China is 1.78 tonnes per hectare. In Taiwan, it is 2 tonnes per hectare.

- Outmoded Mills and Machinery: Most of these jute mills were established some 100 or 150 years back. Naturally most of these mills are having backdated machinery. Output of these machines is very low compared to the modern sophisticated machines. Because of use of these for more than a century, productive capacity has gradually declined.

- Low Demand: Not many people are aware of plastic alternatives like jute. Besides, the misconception that cotton bags are more durable, presentable and nature friendly has resulted in very few people using jute products.

- Pandemic: The coronavirus pandemic has also thwarted hopes of restoring the lost glory of the industry — several mills have shut down and lockdowns have caused labour and raw material shortages.

|

Dire situation

The jute industry of West Bengal primarily supplies its produce to the government of India for food grain packaging. The price of these bags saw a corresponding rise with the spiking rates of raw material. As a result, the union government passed an order in September 2021 to cap the prices of raw jute and B-Twill (the gunny bags used to package food grains) at Rs 6,500 per quintal.

However, the market price of raw jute, as well as its price in Bangladesh, is around Rs 7,200 per quintal, which is why the “industry is forced to buy it at higher prices to keep the mills running”. “The scenario is extremely critical as there is no enough compensation for the prices. And as far as profitability is concerned, it’s a very difficult situation.

In 2021 a notification was issued on increasing the GST rates on jute products from 5% to 12%, worsening their plight.

|

Steps taken by the Government

The following measures have been taken for improving the Jute mills.

- Mandatory use of Jute goods: Mandatory use of Jute bags in food grains and sugar, cement and in fertilizers.

- Modernization and Rationalization: Modernization and rationalization of Jute mills have been undertaken.

- Nationalization of ‘sick’ Jute mills: The National Jute Manufacture Corporation Limited (NJMC) under the Ministry of Textiles has taken over the management of sick Jute mills.

- Under the Jute Packaging Materials (Compulsory Use in Packing Commodities) Act 1987 (JPMA), the government is required to consider and provide for the compulsory use of jute packaging materials for supply. Under unusual circumstances, the central government can allow the use of plastic bags as an alternative for up to 30% of the total requirement for food grains.

- Whenever the market price of raw jute falls below a certain level, the Jute Corporation of India (JCI) procures raw jute at Minimum Support Price (MSP), fixed on the basis of recommendation of the commission for Agricultural Cost and Prices (CACP), from jute growers to safeguard their interest.

- Incentive Scheme for Acquisition of Plants and Machinery (ISAPM): Government of India launched ISAPM for Jute Industry and Jute Diversified Products Manufacturing Units in 2013. The basic aim of this scheme is to facilitate modernization in existing and new jute mills and up- gradation of technology in existing jute mills and to provide assistance to a large number of entrepreneurs to manufacture value added biodegradable Jute Diversified Products (JDP) as well as for modernization Jute up-gradation of technology.

- Jute-ICARE (Jute: Improved Cultivation and Advanced Retting Exercise): This pilot project launched in 2015 is aimed at addressing the difficulties faced by the jute cultivators by providing them certified seeds at subsidized rates, seed drills to facilitate line sowing, nail-weeders to carry out periodic weeding and by popularizing several newly developed retting technologies under water limiting conditions. This has resulted in increased returns to jute farmers.

- The National Jute Board implements various schemes for market development, workers’ welfare and promotion of diversification and exports.

- Government issued a notificationin 2017 imposing Definitive Anti-Dumping Duty on jute goods originating from Bangladesh and Nepal.

- Government has made it mandatory for the entire chain from importers and traders to the level before the end-users, to register with the Office of Jute Commissioner, and furnish monthly reports on the imported goods.

- Government through its Office of Jute Commissioner, Kolkata has also directed all manufacturers, importers processors and traders to mark/ print/ brand the words “Made in- Country of Origin” on imported bags. Customs have also been requested to maintain a strict vigil so that no unregistered importers/ traders can import jute and no unbranded jute goods can enter India.

These measures are not enough to address the looming crisis the industry faces. Lack of implementation of existing initiatives is another problem.

Prospects

- Jute products are in high demand outside India. According to a recent report by Research and Markets, the global jute bag market was valued at $2.07 billion in 2020 and is projected to touch $3.1 billion by 2024, with consumers looking for alternatives to single-use plastic.

- The material's appeal has been boosted by brands such as Dior making jute sandals and stars such as the Duchess of Sussex wearing jute footwear and using hessian gift bags for guests attending her wedding to Prince Harry.

- India should seize the opportunity to invest in its industry and make diverse jute-based products such as rugs, lamps, shoes and shopping bags.

- India's scientists have developed high yielding varieties of jute to tap this renewed interest, but unskilled labour and outdated farming practices meant this had yet to translate into economic returns.

- Environmentalists insist jute has vast economic and green potential, particularly as consumers voice concerns about fast fashion and more countries introduce legislation to ban single-use plastic.

- Every part of the jute plant can be used: the outer layer for the fibre, the woody stem for paper pulp, and the leaves can be cooked and eaten.

- Jute has a great future. It can bring a lot of valuable foreign exchange to the country so the government must focus on this sector.

Way Ahead

- Under the Jute Packaging Act, the percentage of reservation of packaging of foodgrain and sugar into jute bags is reviewed every year. Currently 100 per cent food grains and 20 per cent sugar is mandated to be packed in jute bags. There is a need to restore it to 100 per cent for both.

- India can cater to global demand but for that two things are needed: upgrading the skills of the people...to produce different types of products and upgrading the machinery.

- The need of the hour is to upgrade and adopt new technology, new manufacturing standards and evolve with time.

- Jute needs to diversify its offering into non-packaging segments because it has tremendous potential and uses apart from packaging.

- Handlooms, handicrafts and products made from Jute need to be mainstreamed and adopted on a mass scale in our society.

Jute made products are eco-friendly and can be used to manufacture shopping bags, furnishings, clothing, etc., on a small scale in the rural and sub-urban areas.

- Jute-based lifestyle products can be produced on a large scale and then sold online across e-commerce companies in India and even exported to neighbouring countries. It will help the ailing industry and support the rural economy and empower women

- There is a need for training centres and skills upgrades for increased productivity and improved jute products.

- Since 2011, no major wage revision had been undertaken in the jute industry. Implementation of the Minimum Wages Act, is the need of the hour.

- All stakeholders, including governments, industry bodies, media, and the jute mill associations, have to work in tandem to revive the industry and create public awareness about the use of jute products. The modernisation of jute mills and introducing technology for efficiency will revive the jute industry.

- While the Government can bring forward a policy to aid jute production, we all need to promote products made from Jute to make it more mainstream. In contrast, industry bodies and workers need to adapt to new technology and diversify product offerings.

Case Study: Learning from Bangladesh

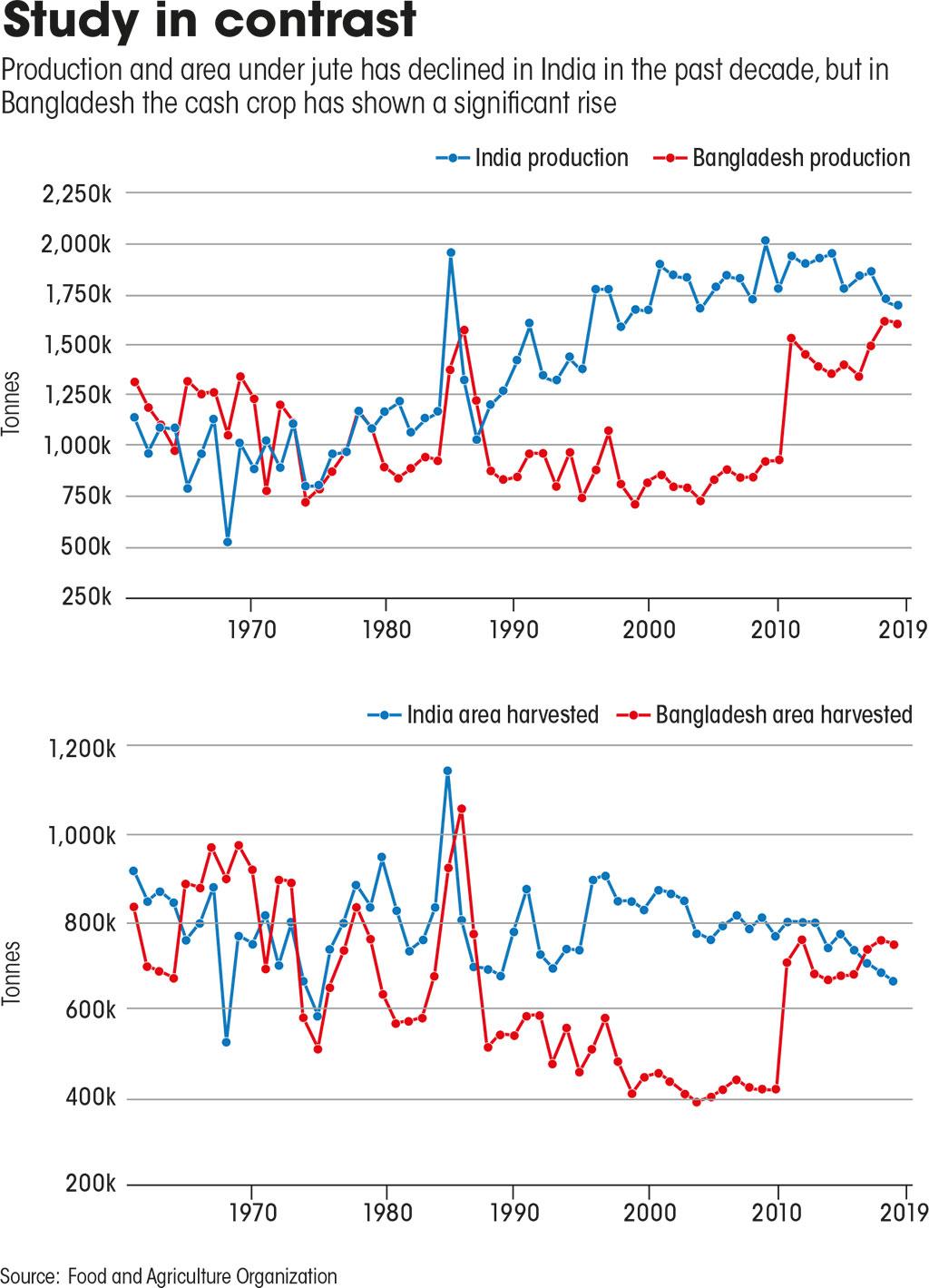

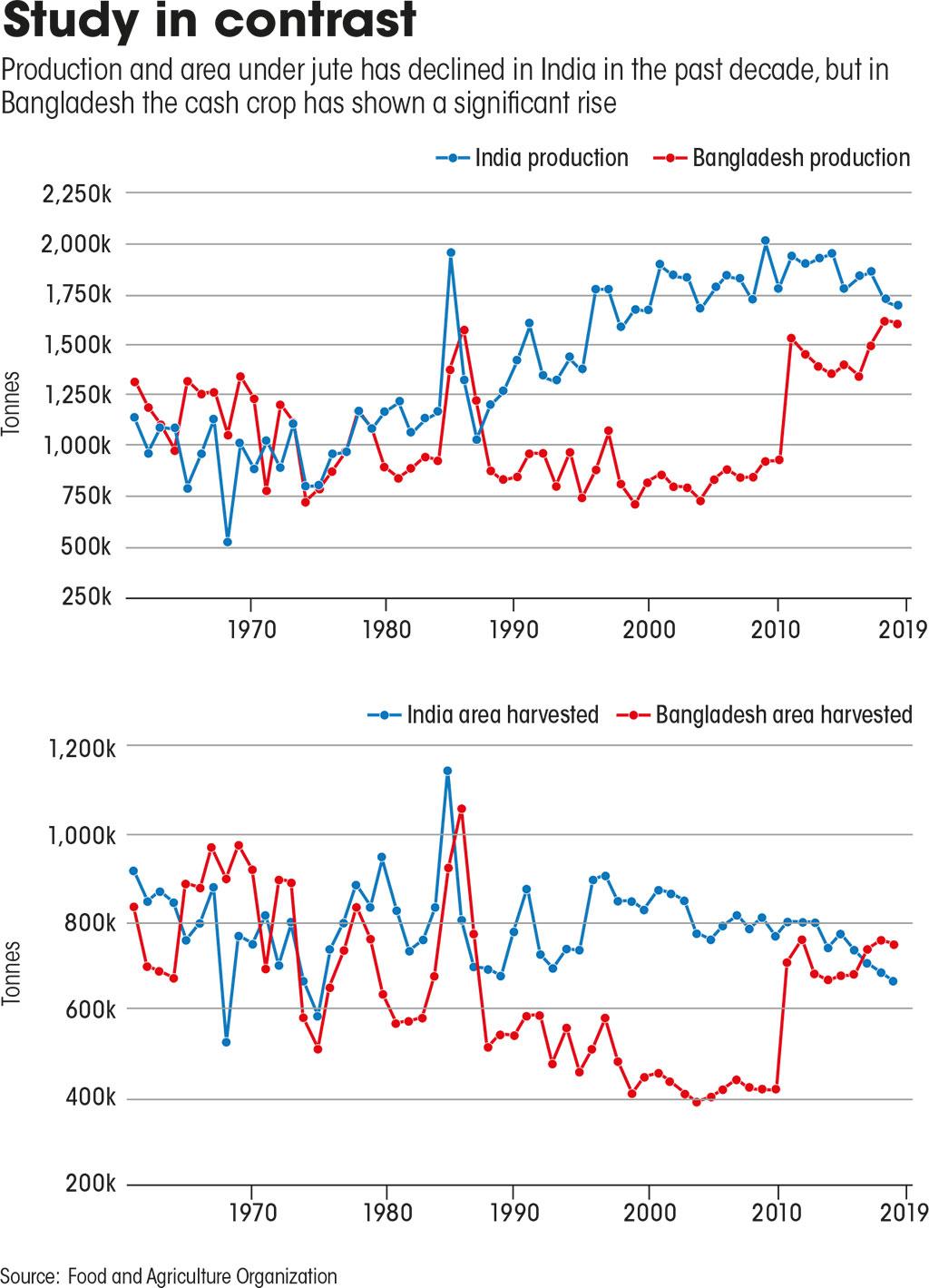

While India’s production and acreage declined, Bangladesh’s production and area under jute has increased over the years.

India is still the largest producer of jute but in terms of acreage, Bangladesh is the largest cultivator. It also accounts for nearly 75 per cent of the global jute exports, while India’s share is just 7 per cent, says the CACP report.

Ironically, even India imports jute products (yarn, floor coverings and jute hessian) from Bangladesh, according to the Union Ministry of Commerce and Industry. In 2020- 21, India imported products worth Rs 1,123 crore from Bangladesh.

The CACP report says imports from Bangladesh have adversely affected the domestic industry, given that the landed price of jute and its products from Bangladesh is less than the domestic rate.

Bangladesh has traditionally enjoyed a comparative advantage in export of jute products because of its low cost of production driven by lower wages, favourable power tariffs, cash subsidy for export and better fibre quality.

Quality, in particular, has been an issue in India’s jute cultivation. Jute in India is marred by poor infrastructural facilities for retting, a process done after harvesting of the crop.

Under retting, jute bundles are kept under water at a depth of about 30 cm. This process gives the fibre its shine, colour, and strength. It should ideally be done in slow moving, clean waterbodies like rivers. But Indian farmers do not have access to such resources.

To overcome such concerns, the Central Research Institute for Jute and Allied Fibres (CRIJAF) under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research has developed a model retting tank with slow moving water. But the technology needs promotion and adaptation.

Bangladesh also does well in exports because it has three to four different kinds of subsidies. For instance, it gives 9-10 per cent export subsidy for food-grade packing bags, which is much higher than India’s 1.5-3 per cent subsidy.

Another reason for the country’s success is its capturing of the diversified jute products market, for which there is a huge international demand. India’s major jute exports, in contrast, are sacking and hessian bags.

Diversification is the key if India wants to make the jute market successful. Demand for diversified products has to be created even domestically. Being environmental friendly, jute has a huge potential in the diversified goods market, especially in regions and nations that have banned plastic. This can be a big boost for a plastic-free India as well.

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/neighbour-s-envy-india-s-jute-economy-is-faltering-while-bangladesh-s-is-flourishing-here-s-why-84063

1.png)