Description

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

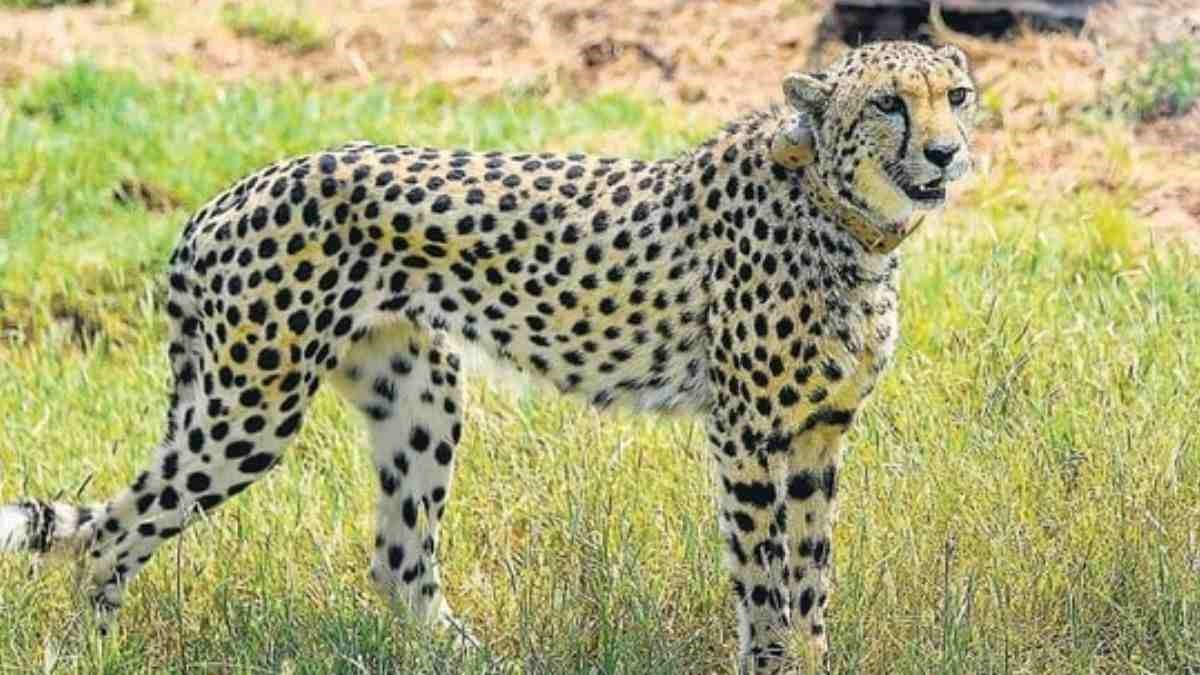

- A year after it was launched, Project Cheetah has claimed to have achieved short-term success on many counts.

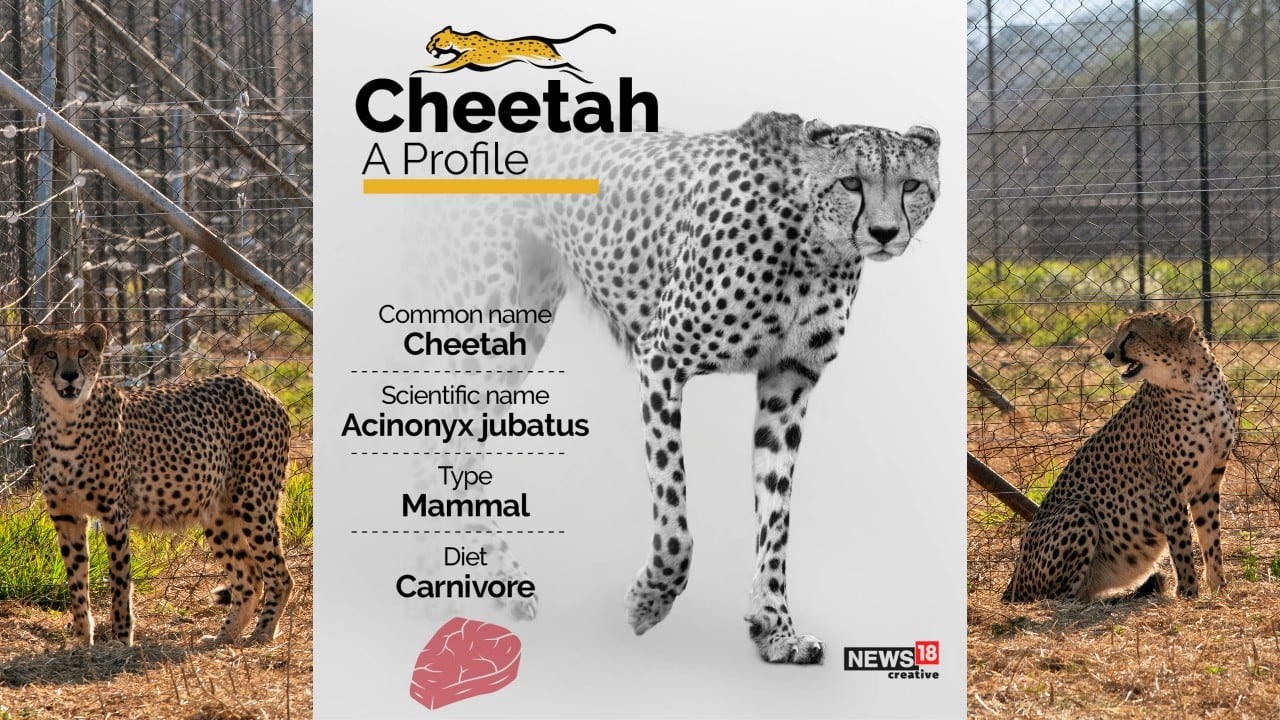

About

- Project Cheetah is India's ambitious initiative to reintroduce cheetahs after their extinction in the country.

Initiation

- The initiative began on September 17 2022, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi released a group of cheetahs brought from Namibia into an enclosure at Madhya Pradesh's Kuno National Park.

Objectives

Project Cheetah aims to achieve the following ecological objectives:

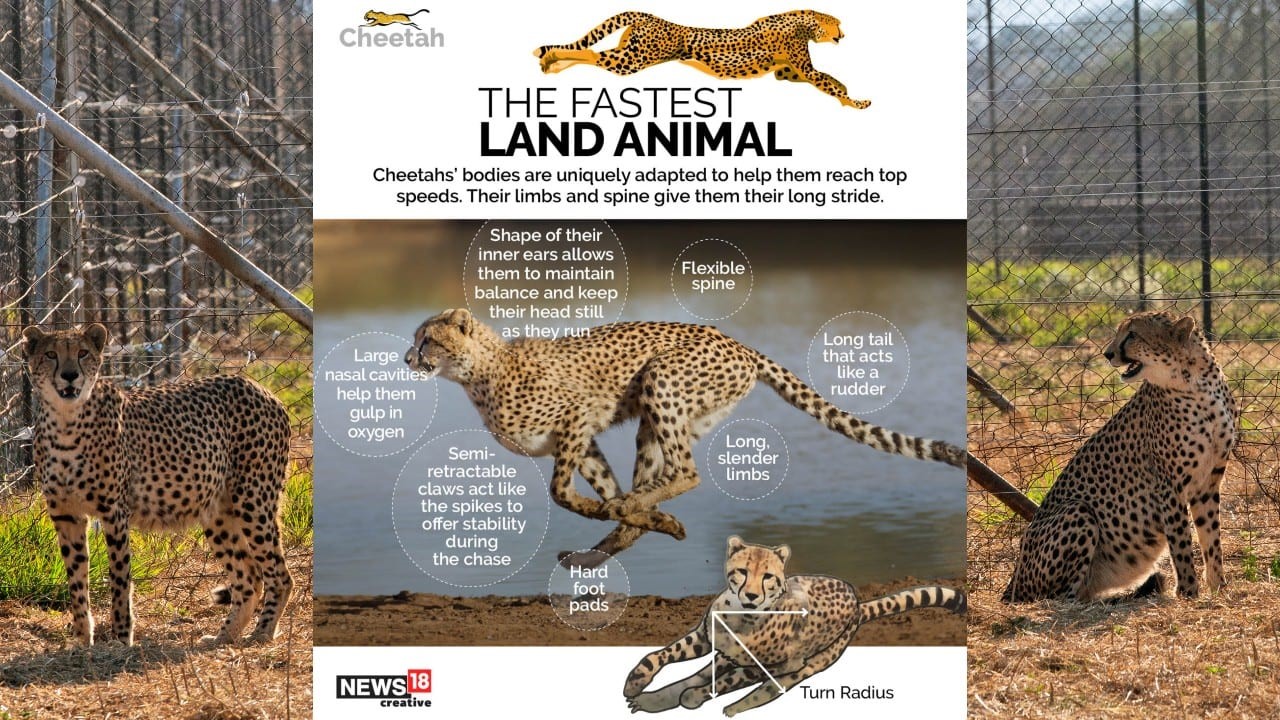

- Re-establish the functional role of the Cheetah in representative ecosystems within its historical range. Here the cheetah will serve as a flagship to save not only its prey-base but also other endangered species of the grassland and semi-arid ecosystems. Resources invested in these highly exploited and neglected systems will ensure better management and restore their ecosystem services for the country.

- Contribute to the global effort towards the conservation of the Cheetah as a species.

- Additionally, Cheetah's introduction is likely to improve and enhance the livelihood options and economies of the local communities.

One year of Project Cheetah

- Project Cheetah has claimed to have achieved short-term success on four counts:

-

- “50% survival of introduced cheetahs,

- the establishment of home ranges,

- birth of cubs in Kuno”, and

- revenue generation for local communities.

The claims assessed

SURVIVAL:

- The test of survival is in the wild, not in captivity where animals are under protective care.

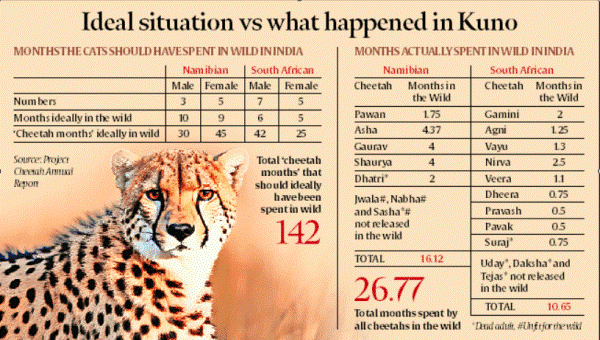

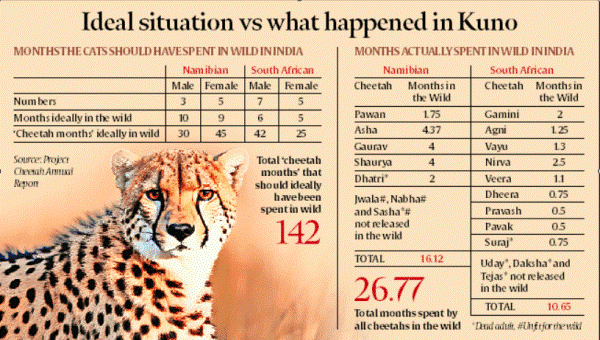

- According to India’s official Cheetah Action Plan, the male and female cats from both Namibia and South Africa were to spend two and three months respectively inside bomas (enclosures) before being released in the wild.

- In the 12 months since they arrived in India in September 2022, the eight cheetah imports from Namibia should have spent a cumulative 75 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- However, in reality, they spent just about 16 ‘cheetah months’ outside the bomas.

- Together, the 12 South African imports should have spent a cumulative 67 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- In reality, as the chart shows, they spent not even 11 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

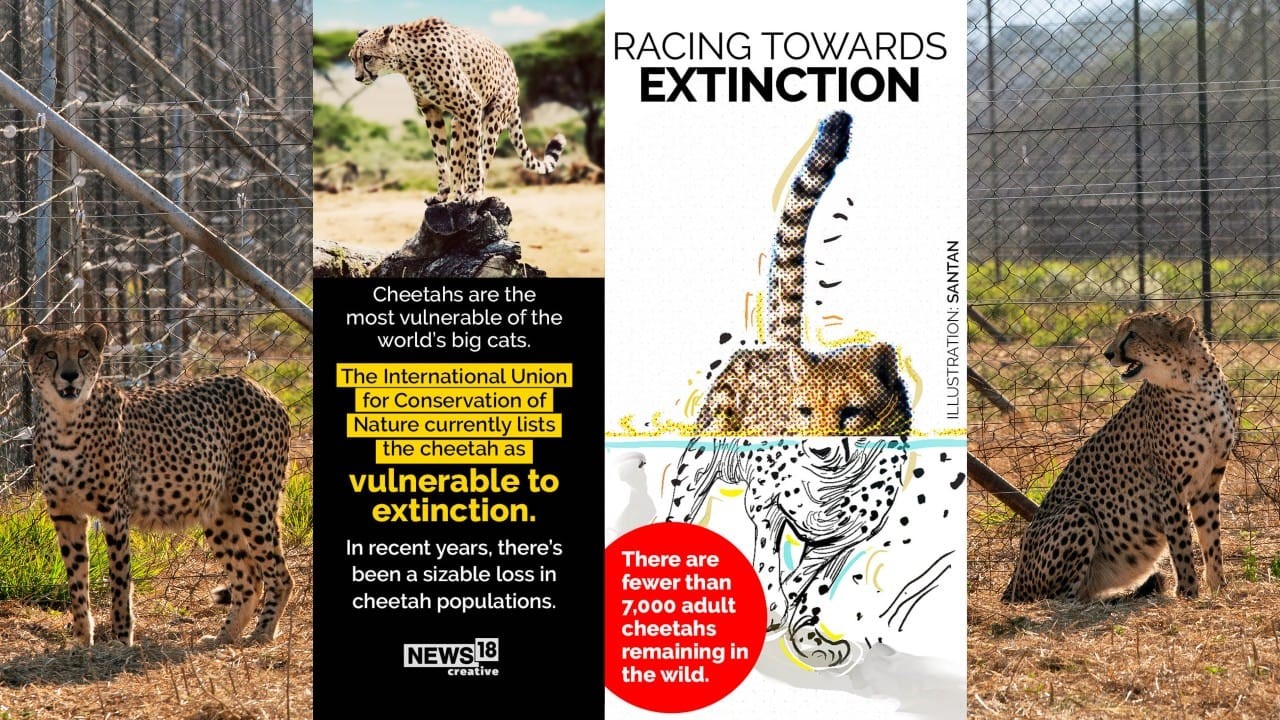

- Yet, the project lost 40% of its functional adult population.

- Of the 20 cats that arrived in India, six died (Dhatri and Sasha from Namibia; Suraj, Uday, Daksha, and Tejas from South Africa), and two were unfit for the wild. Four cubs were born in India, three of which died, and the fourth is being raised in captivity.

HOME RANGE:

- Only three cheetahs — Namibian imports Asha, Gaurav, and Shaurya — have spent more than three months at a stretch in the wild.

- Even they have been stuck inside bomas since July. It is unlikely any of the cats would have established “home ranges” in Kuno.

REPRODUCTION:

- The goal, as per the Action Plan, was: “Cheetah successfully reproduce in the wild”.

- However, Siyaya aka Jwala, the Namibian female that gave birth to four cubs in Kuno, was captive-raised herself.

- She was unfit for the wild and her cubs were born inside a hunting boma.

LIVELIHOOD:

- The project has indeed generated a number of jobs and contracts for the local communities, and the price of land has appreciated significantly around Kuno.

- No human-cheetah conflict has been reported in the area.

Compromises, mistakes

- Three of the eight Namibian cheetahs — Sasha, which was the project’s first casualty, and Jwala and Savannah alias Nabha, who were never released outside the bomas in Kuno — were captive-raised, reportedly as “research subjects”. They were offered to India to meet the “hard deadline” for the import.

- To get the cheetahs, India promised to support Namibia for “sustainable utilisation and management of biodiversity…at international forums”.

- Weeks after the cheetahs arrived, India abandoned its decades-old stand by abstaining at the CITES vote against trade in elephant ivory.

- In Kuno, captive breeding was attempted by putting the sexes together in hunting bomas. However, due to extremely low genetic variation within the species, a cheetah female is very selective in seeking out most distantly related males. That is why giving males access to a female not in heat can lead to violence.

- The project got lucky with Jwala it failed when two South African males killed the female Phinda alias Daksha in May.

- The monitoring teams failed to intervene in time when three cubs succumbed to acute dehydration in May.

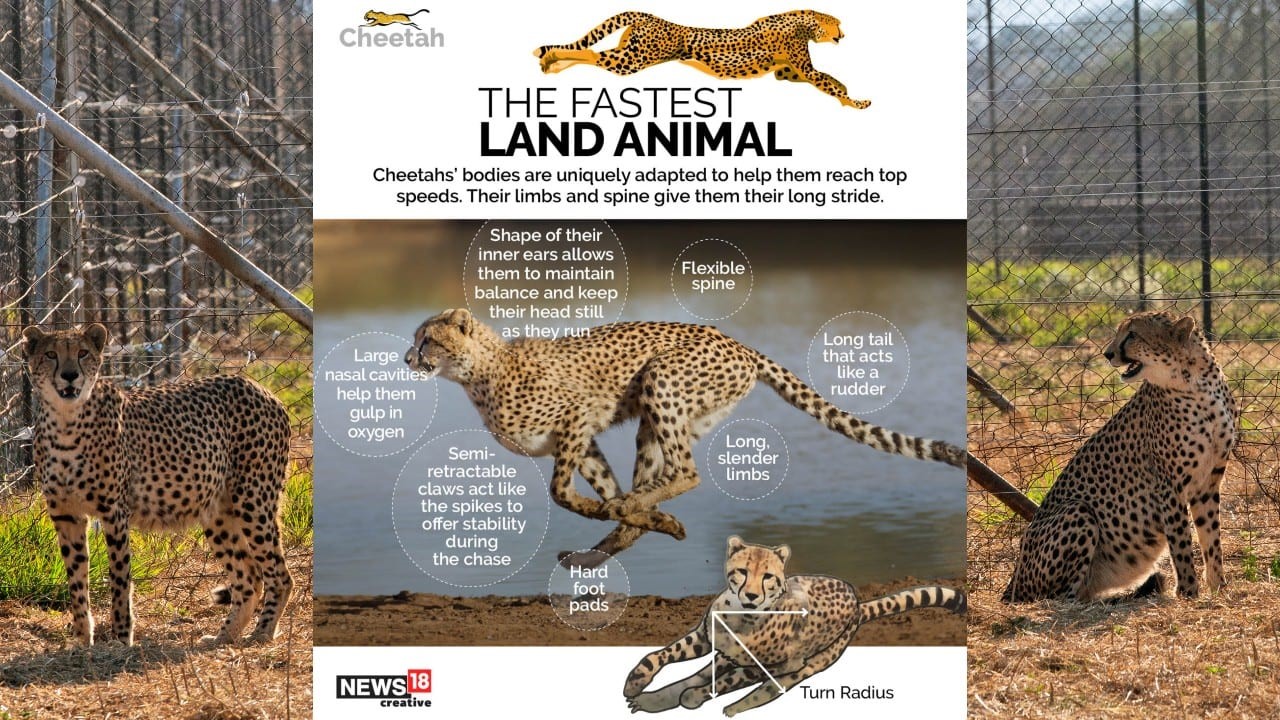

- Maggot infestation in multiple animals — which would have affected their gait — also went unnoticed until the festering wounds under their radio collars killed two in July.

Kuno’s carrying capacity

- The project’s original goal, “to establish a free-ranging breeding population of cheetahs in and around Kuno”, has been diluted to “managing” a meta population through assisted dispersal.

- The Cheetah Action Plan estimated “high probability of long-term cheetah persistence” within populations that exceed 50 individuals.

- Cheetal is the cheetah’s prime prey in Kuno where project scientists reported per-sq-km cheetal density of 5 (2006), 36 (2011), 52 (2012) and 69 (2013).

- The feasibility report in 2010 estimated that 347 sq km of Kuno sanctuary could sustain 27 cheetahs, and the 3,000 sq km larger Kuno landscape could hold 70-100 animals.

- After the project was revived in 2020, the Cheetah Action Plan assessed Kuno’s cheetal density at 38 per sq km which could sustain 21 cheetahs, while a larger landscape of 3,200 sq km could support 36.

- A single population of 50 cheetahs was no longer deemed feasible.

Looking Ahead

- Since Kuno cannot support a genetically self-sustaining population, the project’s only option is a meta-population scattered over central and western India.

- But unlike leopards, which dominate this landscape, cheetahs cannot travel the distances between these pocket populations on their own.

- A solution would be to borrow from the South African model that periodically translocates animals from one fenced reserve to another to maintain genetic viability.

- But if this “assisted dispersal” becomes the new normal, the case for maintaining forest connectivity that allows natural dispersal of wildlife will be severely weakened.

READ:

https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/cheetahs-in-india

https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/cheetah

|

KUNO NATIONAL PARK

Kuno National Park is a national park and Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh. It derives its name from Kuno River. It was established in 1981 as a wildlife sanctuary. In 2018, it was given the status of a national park. It is part of the Khathiar-Gir dry deciduous forests ecoregion.

|

.jpg)

|

PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. Project Cheetah is India's ambitious initiative to reintroduce cheetahs after their extinction in the country. What has been the performance of the Project in the recent past? Evaluate.

|