Copyright infringement not intended

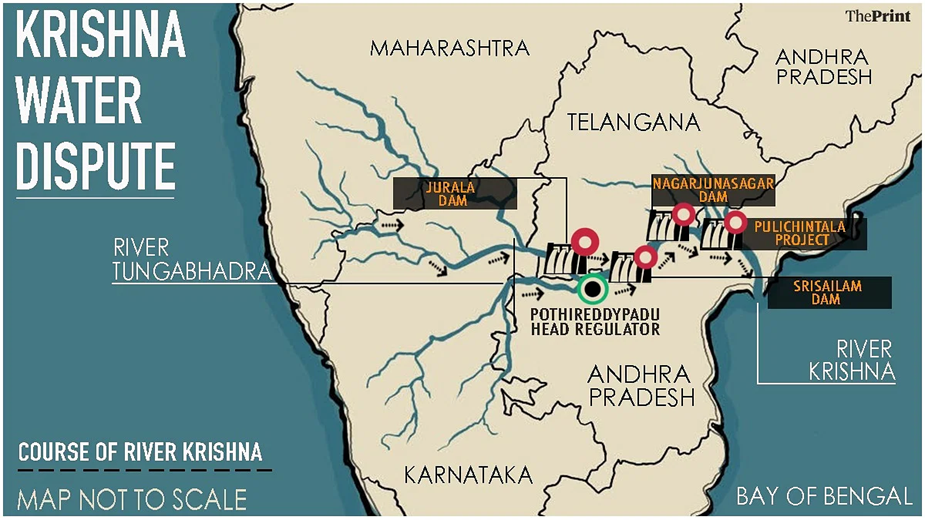

Context: Krishna River water dispute between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh remains unresolved even nine years after the bifurcation of the combined state.

Details

- The Krishna River is one of the major sources of water for the states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. However, the allocation and utilization of its water has been a contentious issue among these states for decades.

Background of the Dispute

1956 Agreement

- The origin of the dispute can be traced back to 1956 when Andhra Pradesh was formed by merging the Telugu-speaking regions of Hyderabad State (Telangana) and Madras State (Andhra).

- An Agreement was signed by four leaders from each region to protect the interests and needs of Telangana concerning water resources.

- Telangana leaders alleged that this agreement was violated by the Andhra-dominated government, which focused on developing irrigation facilities in Andhra at the cost of drought-prone areas in Telangana.

Bachawat Tribunal (1969)

- In 1969, the Bachawat Tribunal (KWDT-I) was constituted to settle the dispute among Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh over the Krishna water share.

- The Tribunal allocated 811 tmcft (thousand million cubic feet) of dependable water to Andhra Pradesh, which was later apportioned between Andhra and Telangana based on the command area developed or utilization mechanism established by then.

- The Tribunal also recommended taking water from the Tungabhadra Dam to the Mahabubnagar district of Telangana, but this was not implemented.

Bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh (2014)

- After the bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh in 2014, there was no mention of water shares in the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, as the KWDT-I Award was still in force.

- However, both states have proposed several new projects on the Krishna River without getting clearance from the Krishna River Management Board (KRMB), the Central Water Commission and the Apex Council, as mandated by the Act.

- The KRMB was set up by the Central government to supervise and regulate the use of water from the Krishna basin by both states.

The main bone of contention

- The main bone of contention between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh is the drawal of water from the Srisailam reservoir, which is constructed across the Krishna River and located in both states.

- Telangana claims that it has a right to use water from Srisailam for power generation as well as irrigation, as it has a lower riparian status and has been deprived of its fair share in the past.

- Andhra Pradesh argues that Telangana is violating the KWDT-I Award and affecting its downstream utilization by drawing excess water from Srisailam for power generation without obtaining clearances from the KRMB.

Recent events

- The dispute has escalated in recent times, with both states filing complaints against each other and deploying police forces at various hydel power projects along the border.

- The KRMB has issued orders to Telangana to stop power generation from Srisailam, but Telangana has defied them.

- The Apex Council, which comprises the Union Water Resources Minister and the Chief Ministers of both states, has not been able to resolve the issue amicably.

Inter-state river water dispute in India

About

- Water is a vital resource for human survival and development. However, water is also a source of conflict among states that share river basins.

- India has 14 major river basins and 44 medium river basins that are inter-state in nature, meaning that they flow through two or more states. These river basins account for 83% of the country's geographical area and 80% of its water resources.

Possible reason

- Interstate river water disputes arise due to disagreements over the use, distribution, and control of interstate river basin waters.

- Increasing demand for water due to population growth, urbanization, industrialization, and agriculture

- Inadequate data and information on river flows, availability, and utilization

- Lack of effective institutional mechanisms for cooperation and coordination among states

- Divergent interests and priorities of states based on their geography, economy, and politics

- Climate change impacts water resources such as variability, uncertainty, and extreme events

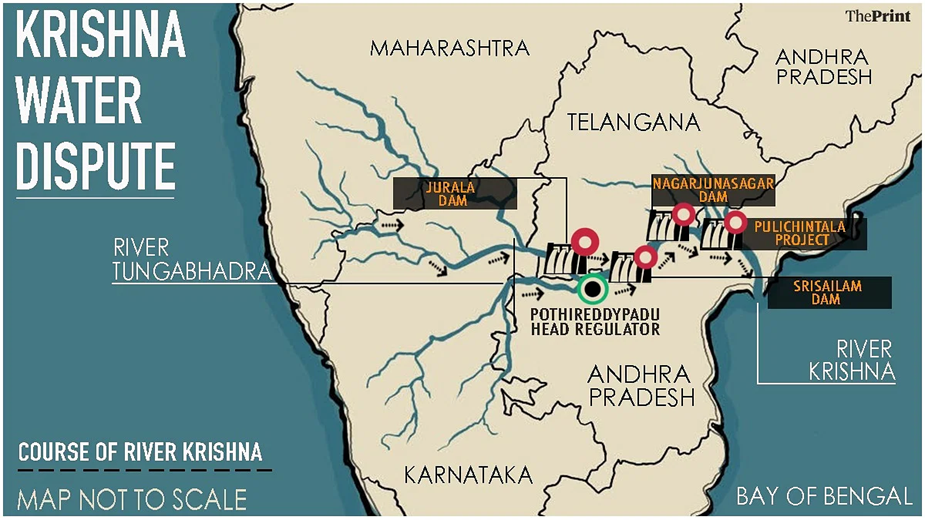

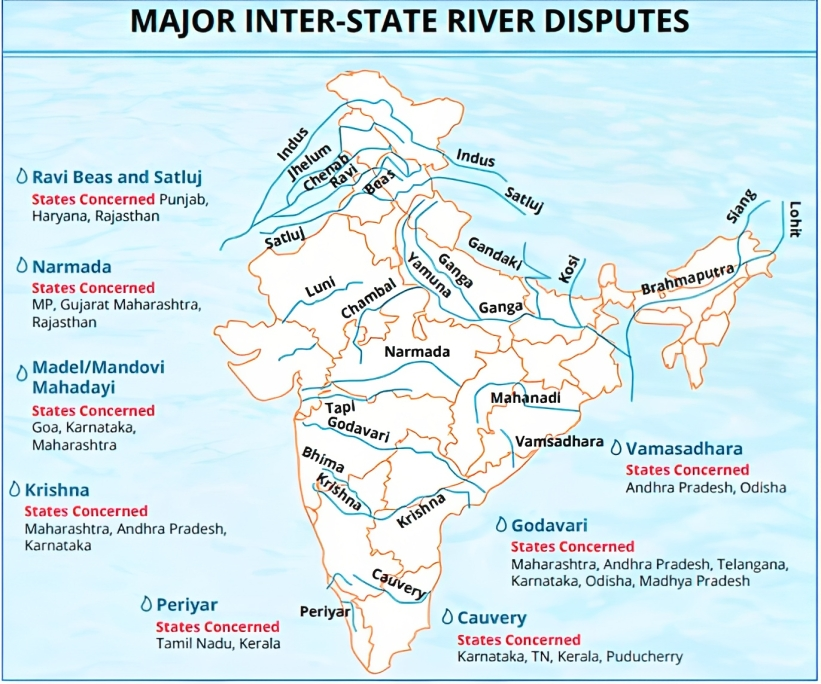

Major inter-state river water disputes in India

- Ravi and Beas: Between Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan over the allocation of surplus waters and the construction of the Satluj-Yamuna Link canal.

- Narmada: Between Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan over the construction of dams and hydropower projects.

- Krishna: Between Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana over the sharing of waters and the implementation of tribunal awards.

- Cauvery: Between Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Puducherry over the sharing of waters and the implementation of tribunal awards.

- Godavari: Between Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha over the construction of dams and barrages.

- Mahanadi: Between Chhattisgarh and Odisha over the construction of dams and barrages.

- Mahadayi: Between Goa, Maharashtra, and Karnataka over the diversion of water for irrigation and drinking purposes.

- Periyar: Between Tamil Nadu and Kerala over the lease agreement and the operation of the Mullaperiyar dam

Challenges posed by these disputes are:

- Delayed and prolonged resolution process due to legal and administrative hurdles.

- Non-compliance and non-implementation of tribunal awards by states.

- Interference of courts and political parties in water matters.

- Social unrest and violence among affected communities.

- Environmental degradation and ecological imbalance due to overexploitation and pollution of rivers

Constitutional Provisions

- The Constitution of India provides for the resolution of inter-state river water disputes under Article 262. According to this article:

- Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint concerning the use, distribution or control of the waters of, or in, any inter-State river or river valley.

- Parliament may by law provide that neither the Supreme Court nor any other court shall exercise jurisdiction in respect of any such dispute or complaint.

In pursuance of Article 262, Parliament has enacted two laws:

The River Boards Act of 1956

- This act empowers the central government to establish river boards for inter-state rivers and river valleys in consultation with state governments.

- The main functions of these boards are to advise on the regulation and development of inter-state rivers and river valleys, to prepare development schemes, to prevent water pollution, and to foster cooperation among states.

- However, this act has not been effectively implemented as no river board has been set up so far under this act.

The Inter-State River Water Disputes Act (ISRWD) 1956

- This act provides for the constitution of tribunals for the adjudication of inter-state river water disputes.

- According to this act, if a state government requests any water dispute and the central government believes that the water dispute cannot be settled by negotiations, then a tribunal is constituted for the adjudication of the water dispute.

- The award of the tribunal is final and binding on the parties to the dispute.

- The act also bars the jurisdiction of any other court in respect of matters referred to a tribunal.

Challenges

Delayed constitution of tribunals

- The act does not specify any time limit for constituting a tribunal after receiving a request from a state government. This leads to prolonged negotiations among states before a tribunal is set up.

Prolonged proceedings and awards

- The act does not specify any time limit for completing the proceedings and giving an award by a tribunal. This leads to protracted litigation and frequent adjournments by tribunals.

Non-implementation or partial implementation of awards

- The act does not provide any mechanism for ensuring compliance with tribunal awards by states. This leads to non-implementation or partial implementation of awards by states due to political or legal reasons.

Multiple tribunals for the same or connected issues

- The act allows for constituting separate tribunals for different disputes arising from the same or connected issues. This leads to overlapping jurisdiction and conflicting awards by different tribunals.

Amendments were made to the ISRWD Act in 2002 and 2019. The main features of these amendments are:

- The time limit for the constitution of tribunals: The amendments mandate that a tribunal shall be constituted within one year from the date of receipt of a request from a state government.

- The time limit for completion of proceedings and awards: The amendments mandate that a tribunal shall complete its proceedings within three years from its constitution. This period may be extended by two years with prior approval from the central government.

- Single permanent tribunal: The amendments provide for setting up a single permanent tribunal with multiple benches instead of separate tribunals for each dispute. The permanent tribunal shall consist

Steps need to be taken to resolve these disputes

- Strengthening the existing legal framework such as the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act 1956 and its amendments.

- Establishing a permanent and independent tribunal for adjudication of all water disputes.

- Promoting cooperative federalism and dialogue among states through platforms such as river boards, inter-state councils, zonal councils, etc.

- Enhancing data sharing and transparency among states through a national water information system.

- Adopting an integrated river basin management approach that considers all aspects of water resources such as quantity, quality, ecology, equity, etc.

- Encouraging participatory and inclusive decision-making involving all stakeholders such as central government, state governments, local bodies, civil society groups, etc.

- Fostering water conservation and efficiency measures such as rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation, reuse and recycling of water, etc.

Way Forward

- The Krishna water dispute between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh is a complex and long-standing one that requires a comprehensive and cooperative solution.

- The two states need to respect each other’s rights and interests and abide by the existing awards and agreements. They also need to seek clearance from the relevant authorities before undertaking any new projects on the river.

- The Central government should play a proactive role in facilitating dialogue and arbitration between them.

- The dispute should be resolved in a manner that ensures equitable and sustainable use of water for all stakeholders.

Must Read Articles:

Interstate River Water Dispute: https://www.iasgyan.in/blogs/interstate-river-water-disputes

|

PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. Interstate river water dispute in India is a complex and contentious issue that affects millions of people and their livelihoods. How can the central and state governments, as well as the various stakeholders, work together to resolve these disputes fairly and sustainably? What are the main challenges and opportunities for cooperation and coordination in this domain? How can the legal and institutional frameworks be improved to facilitate dialogue and negotiation among the parties involved?

|

https://epaper.thehindu.com/ccidist-ws/th/th_delhi/issues/37256/OPS/GG9B93J1I.1.png?cropFromPage=true